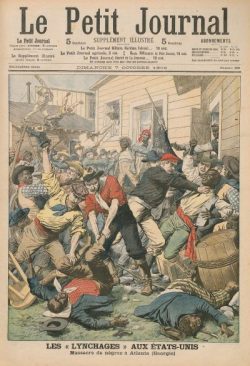

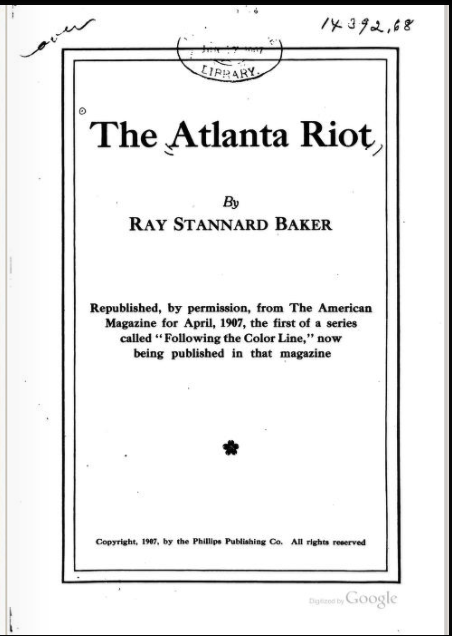

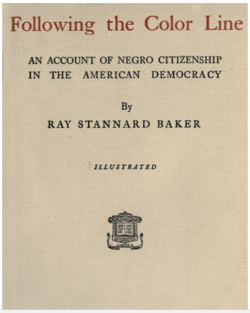

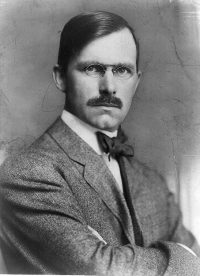

The riots drew muckraking journalist Ray Stannard Baker to Atlanta. From 1907-8, Baker reported on racial issues in magazine articles that became a book, "Following the Color Line"

I have looked at the Negro as a plain human being.

Baker's race reporting is useful for journalism historians because his work reflected the way journalists of his time applied four of the five elements that David Mindich identifies as part of the early definition of "objectivity."

Five characteristics of objectivity

- detachment

- nonpartisanship

- facticity

- inverted pyramid

- balance

At 36, Baker had gained a reputation for exposing thorny social problems, much like Upton Sinclair, Ida Tarbell and Lincoln Steffens. The editors of Booker T. Washington's papers described him as "one of the few reform-minded whites of his day to take a sustained interest in the issue of racial discrimination."

[Ray's] a young person whose mother didn't know he was out.

Baker's reporting featured images and comments from some of Atlanta's leading white and Black citizens, such as Rev. H.H. Proctor.

The Negro has too little confidence in our courts.

We have been disarmed: how shall we protect our lives and property?

He noted the interracial Atlanta Civic League as a hopeful effort to improve race relations. These quotes from white attorney Charles Hopkins and Black physician WF Penn are from Baker's report on a Civic League meeting.

Indeed, Baker said there was a Negro "criminal type" who supposedly ".causes most of the trouble in the South...giving a bad name to the entire Negro race."

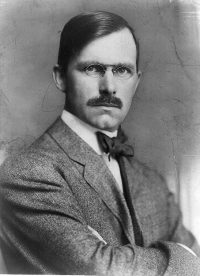

In a memo, Du Bois took issue with Baker's repeated claim that white people were leaving the south for fear of black crime.“The reason for the white people leaving the Black Belt are social and economic and not criminal...There is less crime in the Black Belt than there is anywhere in the South. Less than there is in the white belt, less than there is in the cities. This can be proven by statistics..

In a May 10,1907 letter, Baker defended.his work..

I]t was my observation that in the South, talking with a great number of white people... that fear of Negro crime really is a very potent influence down there, especially among the women.

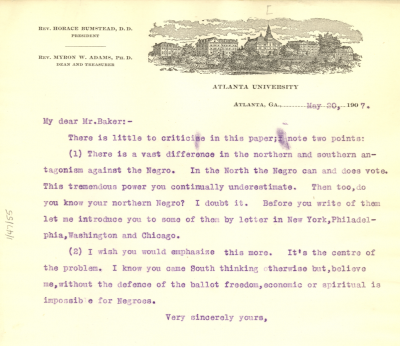

In a May 20 letter on another article draft, Du Bois urged Baker to emphasize black voting rights: "It's the center of the problem. I know you came South thinking otherwise, but, believe me, without the defense of the ballot freedom, economic or spiritual, is impossible for Negroes." Baker's response? "I am especially pleased to know you liked my last two articles..."

In his article, Baker argued,"[T]he vast majority of Negroes (and many foreigners and whites) ... have little or no appreciation of the duties of citizenship. [T]hey should be required to wait before being allowed to vote until they are prepared."(p.303)

It wasn't that Baker didn't see systemic racism. He reported seeing black children as young as six being criminalized. He saw black men being sentenced more harshly for minor offenses such as drunkenness. (p.47-8) He documented the struggle to fund and staff decent schools for black children. He acknowledged racial violence against law-abiding black citizens and the fact that states were profiting from prison labor..

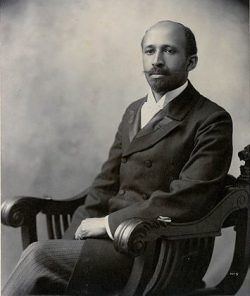

Scholar activists such as DuBois saw these conditions as evidence of a need for fundamental reforms: civil rights, suffrage, and equal access to education.:

By every civilized and peaceful method we must strive for the rights which the world accords to men, clinging unwaveringly to those great words which the sons of the Fathers would fain forget: "We hold these truths to be self-evident: That all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

W. E. B. Du Bois Souls of Black Folk

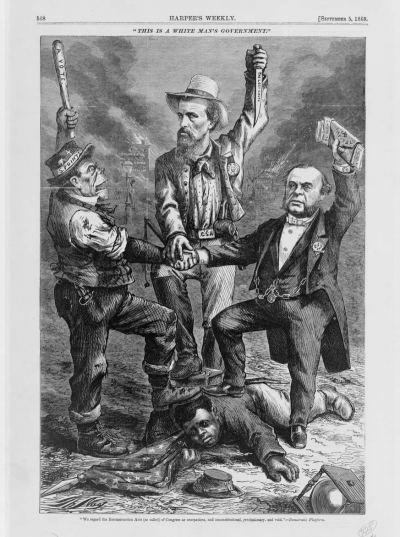

But for Stannard Baker, the solution laid in the kind of "benevolent" paternalism that he imagines existed in the South before the Civil War.

"GENERALLY speaking, the sharpest race prejudice in the South is exhibited by the poorer class of white people, whether farmers, artisans, or unskilled workers, who come into active competition with the Negroes, or from politicians who are seeking the votes of this class of people...."

Baker, Along the Color Line, page 87

Reading Stannard Baker, one would never understand that it was often these same patriarchs who repealed civil rights protections for Black people, created the Black Codes, and systematically limited Black people's efforts to own land, educate their children, and exercise their legal rights.

"The good landlord, generally speaking... is the old slave-owner or his descendant, who not only feels the ancient responsibility of slavery times, but believes that the good treatment of tenants, as a policy, will produce better results than harshness and force."p. 88