Visit NBCNews.com for breaking news, world news, and news about the economy

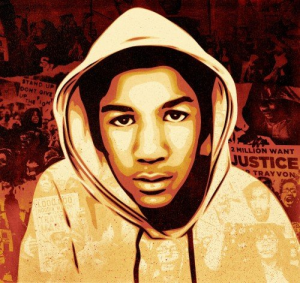

As I write this, Americans are processing the meaning of the not-guilty verdict in the trial of George Zimmerman, the former Sanford, Florida neighborhood watch volunteer who shot and killed 17-year-old Trayvon Martin in February, 2012. Because of the high-profile agitation that led to Zimmerman’s initial arrest and the subsequent gavel-to-gavel coverage of the trial on cable TV, the case has become the latest vehicle for our national non-conversation about race and justice. With the possibility of federal civil rights charges and a wrongful death lawsuit looming against Zimmerman, along with the promise from Zimmerman’s attorney that he will sue NBC for errors in its coverage of the case, it’s likely that we will still be talking about this matter for some time.

No doubt, this case is on the minds of college professors and co-curricular programmers at campuses in the US and elsewhere. TCNJ’s Department of African American Studies, which I chair, held and online discussion of the case in April, 2012. Herewith, a few thoughts and resources that might be helpful in that effort. This is a first take; additions, corrections and suggestions are welcome.

Case Details and Aftermath

- CBS News’ Orlando, Florida affiliate has a timeline of the case from the first 911 calls on Feb. 26, 2012 to the present, with links to its coverage and beyond.

- Trayvon Martin Foundation

- Twitter accout for Tracy Martin (Trayvon Martin’s father) and Sybrina Fulton (Trayvon Martin’s mother)

- George Zimmerman Legal Defense Fund

- New York Times 2012 resource page for educators (secondary school through undergrad level). Includes commentary from teenaged writers and links to early NYT coverage.

- NAACP petition asking the US Department of Justice to file civil rights charges against Zimmerman.

- A round-up of images of protests on the day after the verdict.

Historical and cultural analysis

Politcal historian Jelani Cobb, director of the Institute for African American Studies at the University of Connecticut, penned a series of real-time reflections on the trial for the New Yorker that is concise, informed and provocative. His posts covered

- the defense’s awkward opening with a knock-knock joke,

- a compassionate take on the much-debated testimony of Martin’s friend, Rachel Jeantel;

- questioning whether Trayvon Martin had a right to the “stand your ground defense,”

- what the sympathy for George Zimmerman tells us about popular misconceptions about race and crime

- how the Zimmerman trial reflects a growing American acceptance of racial profiling and surveillance

- why so many African Americans see connections between Zimmerman’s acquittal and the 1955 murder of Emmett Till – and why the criticism that African Americans don’t care about black-on-black murder is wrong

Meanwhile, blogger Andrea Ayers-Deets says the case makes her aware of her “white invisibility cloak.” And The Root has African American views from multiple perspectives, including Ta-Nehesi Coates’ defense of the jury verdict. Susan Brooks Thiselthwaite offers a Christian theological perspective: “For Trayvon Martin, Is There No Justice?” Similarly, Michael Lerner offers a Jewish perspective in his essay, “Trayvon Martin and Tisha B’av: A Jewish Response.” Charles’ Pierce’s sharp irreverent series of posts for Esquire is called the Daily Trayvon. The Huffingtion Post has a dedicated Trayvon Martin section.

Related Cases

For legal scholars, the killing of Trayvon Martin is part of a larger set of cases related to “Stand Your Ground” laws that expand the traditional definition of self-defense and justifiable homicide. Below are links to several cases that have been cited in this context:

- Jordan Davis – the 17-year-old was fatally shot while sitting in a car at a gas station by 45-year-old Michael Dunn, who complained about the loud music emanating from the car’s speakers. Dunn reportedly plans to invoke the Stand Your Ground defense when his trial begins in September.

- Marissa Alexander was sentenced to 20 years in prison in 2012 for firing what she contended were “warning shots” to scare off an abusive ex-husband. No one was harmed in the incident.

- CeCe McDonald pled guilty to second-degree manslaughter in 2012 in a plea deal after surviving what her supporters maintain was a violent, transphobic attack.

- Tremaine McMillen, a 14-year-old Miami boy who was wrestled to the ground, choked and arrested by Miami police who said he “clenched his fists” and gave them “dehumanizing stares.” His family and supporters launched a petition in June asking that felony charges agaginst him be dismissed.

Stand Your Ground Laws, Racism and ALEC

- Sociologist Lisa Wade reviews research findings that Stand Your Ground laws increase racial bias in cases of justifiable homicide. John Roman’s analysis includes data for white-on-white crimes (h/t Diane Bates.)

- A June, 2012 Tampa Bay Times analysis of the application of Florida’s Stand Your Ground law found that white defendants were far more likely to be acquitted than black defendants, along with allowing, “drug dealers to avoid murder charges and gang members to walk free.”

- The Center for Media and Democracy has been closely following the role played by the American Legislative Exchange Council in promoting “Stand Your Grownd” laws across the country as part of its ALEC Exposed project. According to CMD, ALEC used the Florida law as a “template” for “model legislation” that has been enacted across the country.

Implicit Bias, Law and Public Policy

- In the video embedded at the top of this post, Maya Wiley of the Center for Social Inclusion argues that our civil rights laws were designed to address conscious discrimination, but psychology and neuroscience are teaching us that bias operates far more frequently at an unconscious, implicit level. Thus, it is possible that both George Zimmerman’s claim that he held no racial animus against Trayvon Martin and his accusers’ claim that Zimmerman racially profiled the teenager can both be true. Jonathan Martin and Karen Feingold offer thoughts on Defusing Implicit Bias in this 2012 article in the UCLA Law Review that specifically notes the Zimmerman case. Anti=racist educator Tim Wise also has a lot to say on the subject.

Related legal issues

- Shaila Dawan, “Study Finds Blacks Blocked From Southern Juries,” New York Times, June 1, 2010. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/02/us/02jury.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

Artistic responses

- Anthony Branker and Word Play: Ballad for Trayvon Martin, from the album, Uppity

- Watoto of the Nile, “Warning” (Dedication to Trayvon Martin)

- Jasiri X.”Trayvon.”

- Art for Trayvon – Tumblr blog

- Editorial cartoons by Keith Knight, Daryl Cagle‘s cartoon blog