Author’s note: This part of an unpublished 2002 essay, “Not the Subject but the Premise: Postcards from the Edge of Du Bois’ Black Belt,” is reproduced here for comment and as fodder in the body of work upon which I am drawing for my sabbatical project. I consider it to be a failed work with some useful nuggets.

“‘[T]he sheriff came and took my mule and corn and furniture —

‘Furniture?’ I asked; ‘but furniture is exempt from seizure by law.

‘Well, he took it just the same,’ said the hard-faced man.'”

— WEB Du Bois in Dougherty County, Georgia

“Of the Black Belt,” Souls of Black Folk, 1903.’

“It’s alright now/

alright now/

I gave it over to Jesus/

And it’s alright now.”

— sung at St. Mary’s Holiness Church in Hamlet, North Carolina, May, 2002

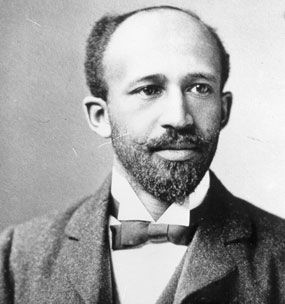

The Forethought: Du Bois the Journalist

Before he became a scholar, activist and would-be Bismarck of his race, William Edward Burghardt Du Bois (1868-1963) was a journalist. As a teenager in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, young Willie was a correspondent for the New York Globe, Freeman and Springfield Republican; at Fisk; he edited the school newspaper. After two commercially unsuccessful attempts to create his own journal of news and opinion, his Crisis magazine would be integral to the birthing of the modern civil rights coalition as well as the Harlem artistic movement of the 1920s. After both of his departures from the NAACP, in 1934 and 1948, he became a regular contributor to several black and later, radical news organs.

and 1948, he became a regular contributor to several black and later, radical news organs.

The Souls of Black Folk is suffused with the best journalistic sensibilities: vivid description, pithy characterization, abundant but carefully chosen detail, and evocative narration. This, along with its seminal influence on racial thought, explains why the faculty of New York University gave Souls and his Crisis columns on race two separate spots on its list of the 100 best works of journalism of the 20th century. (NYU) Despite this, and the growing scholarly attention to Du Bois’ writings, the consideration of his work as journalism has been slight. Most of the attention that has been accorded has gone, understandably, to study of The Crisis.

Du Bois’ reporting was part of an evidentiary brief that, if heeded, would lead to greater support for the policies he advocated for black advancement: fair wages, rents and opportunities for land ownership investment in higher education, and physical safety. In using journalism as one of his weapons, he seems to have understood what media scholar Michael Schudson meant when he declared of 20th century reporting,

“…[T]he power of the media lies not only (and not even primarily) in its power to declare things to be true, but in its power to provide the forms in which the declarations appear. News in a newspaper … has a relationship with the ‘real world,’ not only in content, but in form; that is, in the way the world is incorporated into unquestioned and unnoticed conventions of narration, and then transfigured, no longer a subject for discussion but a premise of any conversation at all.” (Lule)

This essay will consider two journalistic essays in Souls of Black Folk. Particular attention will be given to what Du Bois saw as the proper aim of journalism, and the proper role of the black journalist. The power of Du Bois’ journalism in Souls lies in the specificity with which he placed black life in the context of the social and historical forces that shaped its essential character and defined its structures of opportunity. We get a glimpse of his nascent ability to draw out the multiplicative ways in which African Americans adapted to and agitated against their oppression. However, when viewed in terms of the evolution of racial discourse however, it may be that the most profound effect of Du Bois’ journalism was his ability to demonstrate the centrality of black labor, black culture and black action to American prosperity, identity and well-being. Ironically, we shall see that it is this example that contemporary African American journalists find themselves most challenged to follow.

In Souls, Du Bois the reporter is most evident in Chapters Seven and Eight, “Of the Black Belt” and “Of the Quest of the Golden Fleece.” Both chapters are portraits of Dougherty County, Georgia. As works of journalism, they presage what Tom Wolfe preciously called the New Journalism of the 1960s — the blending of observation, contextual data and narrative technique. There is, however, another way in which the work has contemporary resonance: as a black journalist whose audience and markets crossed racial lines, Du Bois had to grapple with an oppressive and intricate racial ideology that constrained and discounted not only about such southern blacks as were found in Dougherty County, but also educated northern blacks as himself.

discounted not only about such southern blacks as were found in Dougherty County, but also educated northern blacks as himself.

Du Bois had to convince his readers that he was an authoritative interpreter of African American experience – a task made more difficult by the fact that his objective was to supplant what his readers thought they know about his subject. His task was complicated by several unique factors. One the one hand, he had to contend with those who would argue that Du Bois’ mixed racial background made him incapable of understanding the souls of real black folk. On the other, Du Bois faced the personal challenge of understanding people whose skin tones resembled his or his family members, but whose lives under Reconstruction and Jim Crow differed radically from his comparatively Edenic boyhood in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. Finally, he had to contend with emerging standards both of scholarship and of journalism that discounted traditional rhetorical strategies employed by earlier black writers, such as appeals to emotion, biblical authority and first-person narratives.

If he faced unique challenges, Du Bois was also unique in the resources that he brought to the task of destroying and rebuilding the foundations of racial discourse. He could rely not only on his youthful reporting experience, expansive knowledge base and considerable literary gifts, but also the data collection that he was beginning to amass through his work for the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and his direction of the Atlanta University studies. (Lewis, Biography, p. 195) Du Bois was a pioneer in the emerging field of empirical sociology, and the AU studies were part of his lifelong effort to build a comprehensive data portrait of every imaginable aspect of black life — from schooling to economic development to religion and family life. He had invented many of the fields’ methods of data collection and analysis during his first major sociological project, The Philadelphia Negro — among other things, he personally interviewed 3000 black residents of Philadelphia’s seventh ward.

According to Lewis, his principal biographer, Du Bois bragged that his knowledge came from having “lived with the colored people, joined their social life, and visited their homes.” He was particularly scornful of the “car-window sociologist,,, the man who seeks to understand and know the South by devoting a few leisure hours of a holiday trip to unraveling the snarl of centuries….” (Souls, p. 128) In other words, he practiced immersive reporting long before there was a name for it.

Above all, Du Bois struggled to hold to his sense of personal and racial mission. As one of a small number of African Americans who had access to an elite education, Du Bois believed fervently that the future of the race depended on the disciplined, clear-eyed leadership of liberally educated men and women. He had declared, early on, his intention to be one of those leaders. On his 25th birthday, alone in his graduate student quarters at the University of Berlin, Du Bois wrote in his journal, “These are my plans: To make a name in science, to make a name in literature, and thus to raise my race.” (Lewis, Biography, p. 135)

Du Bois was not alone in his efforts to expose the fetid underside of American industrial development. This was, after all, the era of combat between the muckraking journalists and the robber barons. Ida Wells had published her anti-lynching expose, The Red Record. Lincoln Steffens was exposing The Shame of the Cities. Ida Tarbell was publishing her voluminous analysis of Standard Oil.

In fact, Tarbell’s disclosures specifically motivated the Rockefellers to disburse millions to establish the General Education Board (GEB) and the Southern Education Board (SEB) — two foundations that, in the absence of federal involvement in public education, would dominate African American education policy at all levels for decades to come. (Lewis 265-268) Emphasizing ”scientific philanthropy,” the GEB directed most of its funding to industrial and moral education programs at schools such as Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee Institute. The GEB was composed of some of the most powerful men in America, so their positions on black education limned the boundaries of mainstream thinking on race.