After decades of researching my family history, I’ve learned a lot about the people and circumstances who brought me into being. But the effort to destroy, distort and deny the histories of both enslaved and indigenous people means that I’ll probably never know the answers to some basic questions about my ancestry. That has consequences.

When I started researching my family history back in the 1970s, I had to rely on family stories to help me understand the gaps and errors in official documents. Family lore guided me to the name of one of the men who enslaved my paternal ancestors, and that led to his census records. Family lore helped me untangle family secrets – an ancestor born out of wedlock and raised by an uncle, for example, as well as the likely names of that ancestor’s birth parents.

But there are bits of family lore that are difficult to verify because of deliberate erasure by those who were in power at the time. One of the big mysteries has to do with my purported Native American ancestry. To be clear, I know many Black families have these stories – and as the unfortunate example of Sen. Elizabeth Warren shows – so do many White ones. The claims about Native ancestry and their possible meaning both fascinated me and made me uneasy, because I was not one of those Black people trying to claim non-Black ancestors to escape my Blackness. As Zora Neale Hurston put it in her famous essay, “How it Feels to be Colored Me:”

I am colored but I offer nothing in the way of extenuating circumstances except the fact that I am the only Negro in the United States whose grandfather on the mother’s side was not an Indian chief.

“How it Feels to Be Colored Me,” Zora Neal Hurston

Here’s the thing: my maternal grandmother did say that her maternal grandfather, George Ashton, was an Indian community leader, if not an actual chief. She also said her mother, who had died when Grandmom was a little girl, was a full-blooded Native American. My grandmother talked about attending pow wows as a child, but she had little detail to offer. My mother showed me a newspaper clipping about Grandpa Ashton, but of course I couldn’t find it in her things when she died. He died when my mother was only four, so the memories she and her siblings had were slight.

Despite this, the claim to Native ancestry was an important part of the way both my grandmother and mother saw themselves. For a long time, I regarded all of this with mild curiosity and some skepticism. My understanding of what it means to be Native American had been largely shaped by college friends who’ve lived on and off of reservations, who were forced to attend boarding schools, and who have been involved in their tribe’s battles over treaty rights and decent living conditions. To my mind, my grandmother and mother lived lives shaped by the geographies South Philadelphia, Camden, and rural New Jersey and their iterations of African American culture – foodways, religious practices, forms of entertainment, etc.

However, having reconsidered Grandmom’s life and genealogy, I see those memories — and her– differently. My grandmother, Eileen Barnes, was a resourceful matriarch whose character was forged by learning to survive amid ongoing trauma and dislocation. This I knew. I also knew that her grandfather, George Ashton, had been an important person in her life. As I have begun to learn about George Ashton, I’ve begun to realize that I may have missed an important clue about how my grandmother’s identity was formed by George Ashton’s experiences as a Native American in an area where Native identity was ignored or erased.

The events of Grandmom’s early life are stark. She was her parents’ oldest daughter. A brother and two sisters who came quickly after, so she was her mother’s helper. Her mother died when Grandmom was eight.

Her father was a man of grand ambitions, summary judgments, and deep resentments. He told me that around the time my grandmother was born, he got a car and driver’s license. Back then, he said, you just had to send in a fee to the motor vehicles’ office. For a time, he was on the road in search of work and adventure. Eventually, he came back to Philadelphia and plied his trade as a barber, ultimately owning his own shop. After his first wife died, he remarried and had another child. He spoke of his sons with pride; he critiqued his daughters. At the end, it was my Grandmother who coordinated his care, and her sisters who visited. One brother had died decades before. The other sent money but kept his distance.

For a time after her mother’s death, Grandmom lived with her Grandfather Ashton and was embraced by him and his wife. Grandfather George identified as Algonquin. This is when she went to powwows. Years later, when my daughter interviewed her for an elementary school assignment, this was the time that she talked about when asked about her childhood. My grandmother’s identification with her Native ancestry was born of intimate association with the people who had nurtured her.

By the time she was 20, Grandmom was a young wife and mother trying to survive the Great Depression. By 30, she was a widow with five children, her young Army husband having succumbed in a VA hospital after a mysterious illness. By then, Grandpa Ashton was gone, too. For years, I’d heard about her going back to the area where he’d lived and visiting with various people, although no one seemed to know much about who they were.

Grandmom lived for another four decades primarily devoted to her ever-growing family. I would sit with her and count up the number of children (16), grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and great-great-grandchildren. It made her chuckle with wonder. It seemed she always had a child or grandchild staying with her. On Sundays, and especially holidays, she would cook enormous meals and her brood would pass through after church. She learned to play church organ and became a poet as well. Her faith became central to her life, and she worked hard to impart that faith to all of her descendants.

When she died, she was buried in one of several family plots that Grandpa Ashton had purchased decades before. Except for my grandmother and mother, the graves are unmarked. Cemetery records verify that the bodies of my great-great Grandfather George, Great-Grandmother Edna, and one of George’s wives are buried there. (I’m guessing this was the wife he married in 1924 – the one my grandmother knew. The first wife, Edna’s mother, disappears from the public records around the turn of the century.) My mother is interred next to her mother. Grandpa George was still providing for us.

Part of what my grandmother’s life teaches me is that even hidden connections leave legacies. The nurturing my grandmother experienced during her short time among the people she understood to be her indigenous relatives seemed to have forged a lifelong connection, even though there didn’t seem to be a physical community or written history to point to. Like Zora, my grandmother was not “tragically colored.” She was matter-of-fact in saying that her mother was Native and her father had a Black mother and a White father who had not been in his life. She forged her own family and community from those broken pieces.

Sill, it seems that the fragmenting of the Lenni-Lenape might be part of her legacy of intergenerational trauma. It leaves me to wonder whether there’s some set of Ashton relatives cut off from George’s descendants who might know more about his role the hidden history of the Lenni-Lenape in Burlington County, New Jersey.

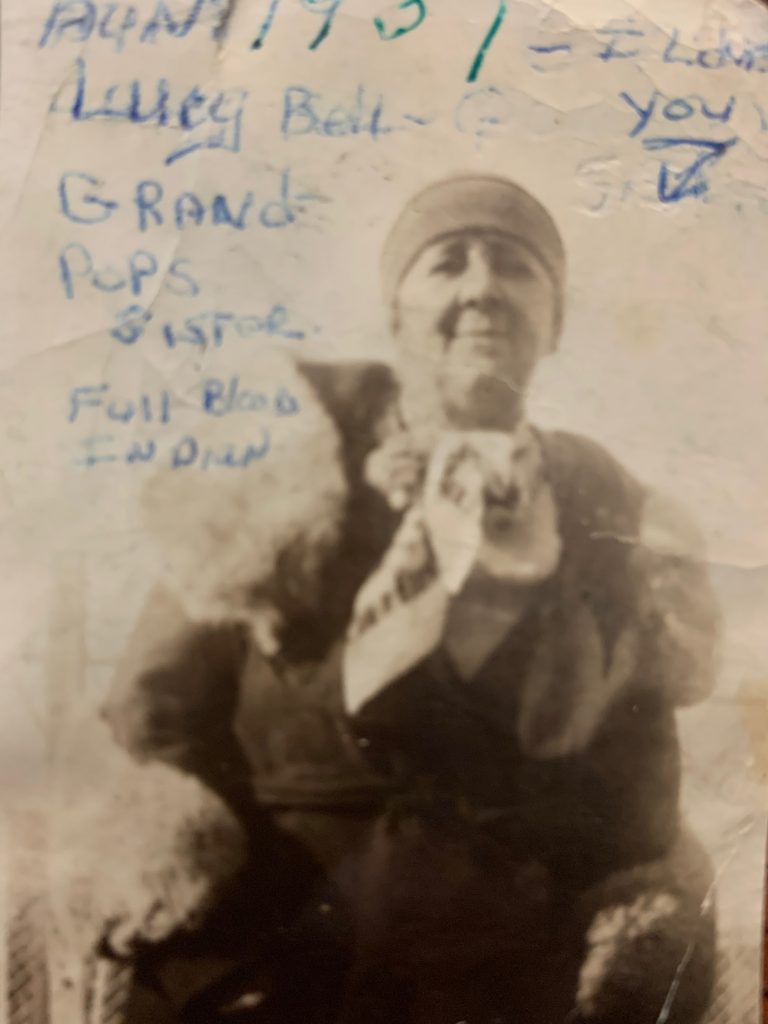

What all the records confirm is that George Ashton was from Shamong, New Jersey, an area historically settled by the Lenni-Lenape. We have a photograph of a woman identified as his sister Lucy Bell. [2022 update: I did find find information on Lucy Bell that led me to census records with the names of their parents and a possible grandmother. Their father’s name was Isaak and his mother, Mary, appears to have come from New York. It also turns out that one my grandmother’s sisters lived with Lucy Bell’s family at the same time that my grandmother lived with Grandpa George. I have been in touch with that sister’s granddaughter, and she is also trying to piece together the same mysteries.]

Official histories say the Lenni-Lenape were pushed out decades before Grandpa Ashton was born in 1861. Only the 1940 census record identifies him as Indian; earlier records identify him as Black or White. However, as the website of the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape attests, there were tribal members who remained in New Jersey and insisted on maintaining their cultural identity even as the majority of their people were forced to go to Oklahoma and elsewhere.

Some helpful insight came from in an email from my friend and TCNJ colleague Dr. Rachel Delgado-Simmons, an anthropologist who formerly worked for the National Museum of the American Indian and who has researched questions surrounding the authenticity of Native American art. According to her, the failure to identify Grandpa George and his family as Indian could have resulted census workers’ ignorance or from government policy not to recognize the existence of Indians in that region.

And some hid their identities to avoid persecution. In a 2007 history of the Nanticoke Lenni Lenape, Rev. Dr. John R. Norwood wrote:

[B]ecause of racial persecution, many eastern tribal families remained in isolated communities and did not seek unwanted attention from outsiders. Cultural activities were not open to the public. Sometimes, even racial misidentification occurred in an effort to clear state and federal obligations to remaining tribal citizens. It was not until the civil rights protections from the 1960s and 1970s that many, previously hidden, eastern tribal communities and their leaders began to openly advocate for their people and promote their heritage to the public.

Indeed, I’ve been told that Grandpa George was aggrieved because he felt he’d been denied certain benefits accorded to tribal members by treaty. Norwood notes treaties between Native American nations in the eastern United States predated the establishment of the nation, and were often breached by subsequent federal and state governments.

Genealogical records, histories such as Norwood’s, and a 1904 list of names of Indians drawn from 18th and 19th century documents have suggestive clues, but no firm evidence of George Ashton’s connection to the tribe. Could “Ashton” have been an anglicization of Ashitaman? If so, he could have been descended from someone who was party to a 1715 contract deeding land to one “Isaac McCow, of Burlington, for a tract on a run called Timaqueekahung…” (p.27) Could he have been related to the woman Norwood identifies as Ann Ashatama Roberts, known as “Indian Ann?” Her father, Elisha Ashatama, was a Lenni Lenape born about 1780. According to Patricia Martinelli’s book, New Jersey Ghost Towns, Ann lived from 1805 to 1894, and was hailed as the last Indian in the area at the time of her death. She married twice. Her formerly enslaved first husband disappeared from the historical record. Her second husband, with whom she had seven children, died in 1852. One of her sons, Paul Roberts, Jr. served with the United States Colored Troops during the Civil War, entitling her to a pension.There are no other identified descendants for Elisha.

Eligibility for tribal membership requires proof of descent from a list of founding families. It also requires proof of at least 25 percent native ancestry and the ability to trace one’s genealogy four generations back. That would mean that the surviving members of my mother’s generation would be eligible if they could identify George Ashton’s parents. There’s a rumor that at least one of my grandmother’s sisters did have tribal citizenship. Her birth certificate says her mother was Indian. By the time I heard the rumor and saw the birth certificate, she was too ill for me to ask her about it.

So, my next steps are to learn more about George Ashton’s first wife, to confirm his mother’s identity, and to enlist the help of a Lenni-Lenape scholar. Reading the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape website, it’s clear that tribal leaders are working hard to reconstruct their stories and culture, so maybe there’s room for collaboration. In the meantime, I share this video from the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape website. It enlarged my perspective on what it means to be Native American in a nation that only sees Black and White.

![]() On measuring the presence of absence by Kim Pearson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

On measuring the presence of absence by Kim Pearson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.