In my last post on the newsgames course I will be teaching this fall, I began to discuss how the need to respect the journalistic intent of a newsgame translates into requirements and constraints upon the game’s design and production. In this post, I want to delve into that topic more deeply, using principles outlined in Tracy Fullerton’s Game Design Workshop: A Playcentric Approach to Designing Innovative Games, and applying those principles to a game that I consider particularly successful, MSNBC’s “Can You Spot the Threats?” game about the challenges of screening airport baggage. Finally, I will discuss questions that I will raise with my students about my partially finished “Food Stamps Game,” which I introduced in the last post. The intent of the Food Stamps Game is to simulate the experience of trying to buy a week’s worth of groceries on a $30 budget, about average in terms of what states allow a single adult participating in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) which is the current name for Food Stamps. (Eligibility for benefits and benefit levels vary, and are based on complex criteria. See references on benefits at the end of this post.)

Fullerton defines a game as:

- A closed formal system that

- Engages players in structured conflict and

- Resolves its uncertainty in unequal outcomse (p, 43)

Here, an aside: It should be noted that Fullerton’s definition of a game is at slight variance with that employed by the authors of the other text that I plan to use in the course, Newsgames: Journalism at Play, which I discussed in the previous post. The Newgames text considers animated infographics as games, where as Fullerton is more restrictive. I bring this up because this is an interdisciplinary class in which some of the students are already familiar with Fullerton;s formulations. I may need to take these differing perspectives into account in order to build a common intellectual climate within the class.

Part of the value of Fullerton’s definition is that she breaks it down into components that can be understood as operational requirements. Games have what Fullerton describes as formal elements (such as rules, playing pieces, boundaries and outcomes), dramatic elements (premise, setting, character and a dramatic arc), and system dynamics (the way the formal and dramatic elements interact). Please note that Fullerton’s definition of these categories is more extensive than I have presented here. This list is only for the sake of illustration and discussion.

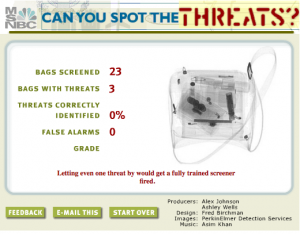

Applying Fullerton’s rubric to MSNBC’s “Can You Spot the Threats” game helps us to understand more about her categories, as well as the characteristics of a successful simulation-type game. The game starts with ominous music and a voiceover narration about the ways in which airport baggage screening procedures changed in the United States after the terrorist attacks of 9/11. Then you are told that you are about to experience what it’s like to screen baggage for two minutes. A series of actual images of luggage generated by screening equipment scrolls across the screen, and you have to pick out the bags most likely to contain guns, knives or explosives. However, the pictures are frustratingly blurry and vague, as can be seen above. You can stop an image, zoom in, and change the black-and-white image to color, but the images are still non-descript. Take too long, and the passenger murmuring in the background rises to a fever pitch. Move too quickly, and it’s likely that something dangerous will slip through. At the end of two minutes, you get a score based on the number of bags screened, the number of dangerous bags detected, the number missed, and a score.

In Fullerton’s parlance, there are formal elements – rules, resources (the bags, the controls), boundaries (the time limit, for example) and outcomes. There is a real-world premise, a story in with characters (you, the baggage screener, and the passengers), a setting, and a simple dramatic arc. The flash program functions efficiently, and the interface is clean.

“Can You Spot the Threats?” is one of the most effective newsgames I’ve seen, both When I had a class of about 24 students play this game in 2003, they said they gained a new appreciation for the difficulty of the baggage-screener’s job, and motivated them to read the accompanying web feature article. My campus is an hour’s train ride from Ground Zero, and the 9/11 attacks were still evoked a visceral emotional response from my students. They said they found it easy to accept the game’s premise, and they felt anxious as the blurry images rolled across the screen and passengers began to complain that they might miss their planes.

These are some of the ways in which the Food Stamps game is unfinished and needs revision. As some test users report, the boundaries of the game aren’t always clear – for example, a script that should come up when a buyer runs out of money doesn’t yet work properly. There aren’t enough dramatic elements and the system dynamics could use some work. These will be some of the things that will be fodder for discussion with students in the fall.

Arguably, the flaws in this game, and the ability to download and remix the code in Scratch, makes the Food Stamps game useful as a tool for highlighting this game and its design process as an example of computational thinking. I will elaborate on that in the next post.

Endnotes

References on benefits. For more information on how states calculate Food Stamp benefits, please see examples below:

- USDA SNAP Eligibility page

- Texas: Food Stamp Benefit Estimator

- Illinois: DHS Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

- MassLegal Services. 2011 Food Stamp Advocacy Guide Part III. Eligibility

- Hawaii Financial and SNAP Benefits RIghts and Responsibilities

- Louisiana Department of Children and Family Services: Economic Stability Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

- South Carolina Department of Social Services SNAP Benefit Calculator

- 2007 Congressional Food Stamp Challenge

- US Food Policy “Living on a Food Stamp Budget” (This is the specific source of my $30/week figure.

Course syllabus as of July 13, 2001