(Richmond Va. September 29 ) —

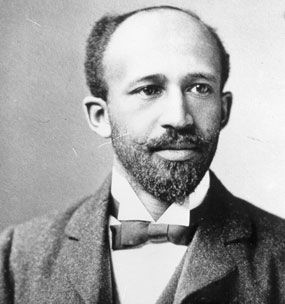

I am on an Amtrak train barreling south toward Raleigh, North Carolina for the 95th annual convention of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History. It is a strange time to be in Raleigh in some ways, so near Duke University, where the towering scholar John Hope Franklin made his professional home for so many years. Next to ASALH founder Carter G. Woodson and Woodson’s contemporary WEB Du Bois, it is difficult to think of another academic historian whose work did more to correct the mistaken but popular belief that slavery was the beginning and end of the story of black people. Duke has a research center that bears Franklin’s name. ASALH’s journal archives and merchandise offerings include articles by Franklin and video interviews recording both intellectual and personal reflections on his life and work.

I am on an Amtrak train barreling south toward Raleigh, North Carolina for the 95th annual convention of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History. It is a strange time to be in Raleigh in some ways, so near Duke University, where the towering scholar John Hope Franklin made his professional home for so many years. Next to ASALH founder Carter G. Woodson and Woodson’s contemporary WEB Du Bois, it is difficult to think of another academic historian whose work did more to correct the mistaken but popular belief that slavery was the beginning and end of the story of black people. Duke has a research center that bears Franklin’s name. ASALH’s journal archives and merchandise offerings include articles by Franklin and video interviews recording both intellectual and personal reflections on his life and work.

I expect that Franklin’s ideas and research will be everywhere at this convention, but the man will not. He died in March, 2009, as the nation was adjusting itself to the reality of having a President of visibly African descent. And yet, the historical moments that marked Franklin’s entry and exit speak volumes about the nature of history as a weapon, the lessons of past wars, and the challenge now confronting those of us who believe in using knowledge to improve the human condition.

1915

Franklin was born on January 2. 1915; it would turn out to be a

momentous year for the United States, not just the Franklin family. If there was ever a moment that attested to the power that historians can wield, this was it. The president of the United States, Woodrow Wilson, held a Ph.D. in history. After promising to be a civil rights advocate to get black votes during the election of 1912, Wilson segregated the federal workforce, dismissing an appeal from civil rights leader Monroe Trotter with the contention that, “Segregation is not humiliating, but a benefit…

Quotes from the fifth volume of Wilson’s encylopedic, “History of the American People,” had been used by filmmaker DW Griffith to lend credibility to his cinematic bouquet to the Ku Klux Klan, Birth of a Nation. Wilson screened the film in the White House, proclaiming it, “History written in lightning!” Protests from the National Association of Colored People and black newsThe KKK, weakened during the Grant administration, once again became a force in national life, with deadly consequences. Wilson also ordered American troops into Haiti in 1915 in what James Weldon Johnson’s investigative reporting revealed as an “imperialistic venture” that became “a dark blot on the American escutcheon.” Wilson’s scholarly expertise helped him fit these and other anti-democratic actions into an argument that, as he said of America’s entry into World War I, his administration was making the world “safe for democracy.”

Franklin’s birth year also coincided with the death of Booker T. Washington, founder of Tuskegee Institute (now University), the “Great Accommodator” who counseled blacks to patiently acquiesce to Jim Crow, develop their moral character and focus on vocational education and business development. In his autobiography, Up From Slavery Washington argued that following his advice would surely elicit the good will of the white power structure and result in fairer treatment for African Americans over time:

My own belief is, although I have never before said so in so many words, that the time will come when the Negro in the South will be accorded all the political rights which his ability, character, and material possessions entitle him to. I think, though, that the opportunity to freely exercise such political rights will not come in any large degree through outside or artificial forcing, but will be accorded to the Negro by the Southern white people themselves, and that they will protect him in the exercise of those rights.

As if to underscore the growing rejection of the accommodationist doctrine among African Americans and their allies, the premiere of Birth of a Nation that year occasioned wide-scale protests from both the NAACP and black newspapers such as Charlotta Bass’ California Eagle. We now know, of course that Washington himself was secretly engaged in some civil rights agitation of his own, by lending financial and material support to lawsuits aimed at attacking disfranchisment and segregated public accomodations, and unequal treatment in the criminal justice system.

From his earliest days, Franklin absorbed both the realities of racism and the belief that it had to be met with rigorous preparation of character and the determined pursuit of justice. The child of a lawyer father and a mother who was both a teacher and entrepreneur, Franklin was named for John Hope, then president of Morehouse College, and after 1929, president of Atlanta University. Hope had taught John Hope Franklin’s father, first at Roger Williams University, then Morehouse. had dared to envision an institution of higher learning where black youth were assumed to be capable of serious intellectual work. In this, he was allied with other black intellectuals such as the protean scholar-activist WEB Du Bois, the founder of Atlanta’s sociology department.

The child of a lawyer father and a mother who was both a teacher and entrepreneur, Franklin was named for John Hope, then president of Morehouse College, and after 1929, president of Atlanta University. Hope had taught John Hope Franklin’s father, first at Roger Williams University, then Morehouse. had dared to envision an institution of higher learning where black youth were assumed to be capable of serious intellectual work. In this, he was allied with other black intellectuals such as the protean scholar-activist WEB Du Bois, the founder of Atlanta’s sociology department.

Like Hope, Du Bois believed that the truths revealed by rigorous research were the foundation on which public policy and civil rights advocacy should be based. Sometimes that research led to a starting and prescient view of world events, as in his May, 1915 essay, “African Roots of War.” While the US and its allies cast World War I as a battle to defend democracy, Du Bois cast it as a battle among Western powers to control the resources and markets of non-Western territories, especially in Africa:

“The present world war is, then, the result of jealousies engendered by the recent rise of armed national associations of labor and capital, whose aim is the exploitation of the wealth of the world mainly outside the European circle of nations. These associations, grown jealous and suspicious at the division of the spoils of trade-empire, are fighting to enlarge their respective shares; they look for expansion, not in Europe but in Asia, and particularly in Africa. ‘We want no inch of French territory,’ said Germany to England, but Germany was ‘unable to give’ similar assurances as to France in Africa.”

This is the kind of analysis that would be hotly debated in the coming years at ASALH conventions, and in the pages of the journals that it would come to publish, the Journal of African American History, the Black History Bulletin. and more recently, the Woodson Review

A Portrait of the Scholar as a Young Man

Like Hope and Du Bois, Franklin would hew to this creed as part of the next generation of scholars. He would take Du Bois’ example so seriously that he followed the elder scholar’s educational path: undergraduate study at Fisk, followed by a Ph.D. in history at Harvard. In his 2005 autobiography, A Mirror to America, he wrote,

“[I]t was armed with the tools of scholarship that I strove to dismantle those [racially restrictive] laws, level those obstacles and disadvantages, and replace superstitions with humane dignity.”

Carter G. Woodson’s ASALH would prove invaluable to the fulfillment of Franklin’s quest. Woodson, the second African American to earn a Ph. D. at Harvard after Du Bois, founded ASALH to promote, create and disseminate accurate information about African Americans not only among scholars and policymakers, but in homes, churches and communities. I’ve written elsewhere about the role that ASALH’s encyclopedias played in helping me see possibilities for myself beyond my limited childhood circumstances. In his autobiography, Franklin captures part of what is special about the ASALH annual conference in this description of the first one he attended, in 1936:

“The remarkable thing about this meeting, although I did not know it at the time, was how schoolteachers and laypeople were as much a part of the organization as the professionals. Dr. Woodson, serving as executive director, cultivated the teachers, for he was as determined to see Negro history taught in the schools as he was devoted to scholarship in the colleges. Thus, several schoolteachers read papers on the inclusion of Negro History in their school’s curriculum as, indeed, did several college professors.

“Dr. Woodson likewise emphasized the importance of making the association racially inclusive. Virginia’s white superintendent of education, Sidney Hall, as well as W. Herman Bell of Hampdon-Sydney College, Garnett Ryland of the University or Richmond, and other white scholars were in attendance.”

Franklin went on to describe how Woodson encouraged non-historians to assume leadership positions in the organizations, citing the 1936 election of Mary McLeod Bethune to the organization’s presidency. Franklin reports that he found himself invited to breakfast with Mrs. Bethune and others on the morning of her election, which came while she was on leave from the presidency of Bethune-Cookman college in order to serve in the Roosevelt administration. while at the convention, Franklin received word that his mother was seriously ill in Oklahoma. Both the president of Virginia State College, which was hosting the event, and Woodson himself offer him travel money to get home.

.

Everything Franklin describes about the convention he attended in 1936 reminds me of what I’ve seen during my attendance at prior ASALH conventions during the past decade. One still sees active involvement of lay historians and K-12 teachers alongside emerging and established scholars. Non-historians still have prominent leadership roles (including yours truly – I have served on the organization’s advisory board alongside Dr. Franklin and such prominent scholars as Henry Louis Gates, director of the WEB Du Bois Institute of Afro-American Studies at Harvard.)

Most impressive to me, the ethic of care between older and younger scholars is still very much in evidence. Talk to young academics who come to ASALH, and it is not unusual to hear them express their delight that a luminary such as Nell Painter, Darlene Clark Hine, or John Bracey or Daryl Michael Scott took the time to come to their session,or offer advice. I still recall my own delight at the 2003 convention when I happened to find myself in conversation with Dr. Edna McKenzie, a historian who began her career as a pioneering journalist documenting segregation in World War II-era Pittsburgh.

I have spent some time discussing the open and nurturing atmosphere at ASALH because I think it is essential to understanding how scholars such as Franklin, and indeed, Woodson himself, persevered in fostering the academic study of African Americans in the face of persistent ignorance and hostility. Franklin went on to produce books such as From Slavery to Freedom: a history of African Americans, which has remained in print for more than 60 years, and to become a nationally-respected authority on race. While the study of African American history and life is more widely accepted than it was in the early days of ASALH, serious students of history again find their field subjected to political forces that would discard and distort the historical record in favor of ideology. The most egregious recent example is the Texas school board’s euphemistic description of slavery as the “triangular trade.” There have, however, been other examples, such as the Christian school in North Carolina that gave students a pamphlet excusing slavery.

I have spent some time discussing the open and nurturing atmosphere at ASALH because I think it is essential to understanding how scholars such as Franklin, and indeed, Woodson himself, persevered in fostering the academic study of African Americans in the face of persistent ignorance and hostility. Franklin went on to produce books such as From Slavery to Freedom: a history of African Americans, which has remained in print for more than 60 years, and to become a nationally-respected authority on race. While the study of African American history and life is more widely accepted than it was in the early days of ASALH, serious students of history again find their field subjected to political forces that would discard and distort the historical record in favor of ideology. The most egregious recent example is the Texas school board’s euphemistic description of slavery as the “triangular trade.” There have, however, been other examples, such as the Christian school in North Carolina that gave students a pamphlet excusing slavery.

So on to ASALH, and a gimpse of new tomorrows through the lenses of the past.