Author’s note: This part of my unpublished 2002 essay, “Not the Subject but the Premise: Postcards from the Edge of Du Bois’ Black Belt,” is reproduced here for comment and as fodder in the body of work upon which I am drawing for my sabbatical project. I consider it to be a failed work with some useful nuggets.

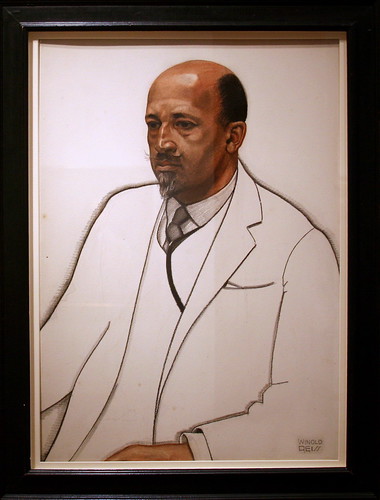

There were few institutions that escaped Du Bois’s critique, and the media was no exception. As editor of The Crisis, “[H]e challenged African-American newspapers to report on more serious social matters than weddings and murders,” David Levering Lewis recalled. (Biography, p. 416) Near the end of his life, Du Bois delivered his own considered judgment on the function and impact of mass media under monopoly capitalism. In a 1953 article in the Monthly Review, he declared,

of The Crisis, “[H]e challenged African-American newspapers to report on more serious social matters than weddings and murders,” David Levering Lewis recalled. (Biography, p. 416) Near the end of his life, Du Bois delivered his own considered judgment on the function and impact of mass media under monopoly capitalism. In a 1953 article in the Monthly Review, he declared,

“The organized effort of American industry to usurp government surpasses anything in modern history. From the use of psychology to spread the truth has come the use of organized gathering of news to guide public opinion and then deliberately to mislead it by scientific advertising and propaganda. This has led in our day to suppression of truth, omission of facts, misinterpretation of news, and deliberate falsehood on a wide scale. Mass capitalistic control of books and periodicals, news gathering and distribution, radio, cinema, and television has made the throttling of democracy possible and the distortion of education and failure of justice widespread.” (Lewis, Reader)

Just as the journalism of Du Bois’ era reflected the technological, political and cultural impact of the emergence of monopoly capitalism, contemporary journalists are struggling with the impact of the information-driven post-industrial economy. Black journalists are struggling not only to hold their own in an uncertain industry, but with their own sense of personal and professional mission.

“The media have an agenda,” says Natalie Byfield, former reporter for the New York Daily News, “and the agenda is to put across the message that the system works – whether it does or not.” (Byfield) Depending upon their experience and their underlying belief system, their conclusions about what’s not working may vary, but the disillusionment does not. As former Washington Post staffer and New York University professor Pamela Newkirk explained, “While black journalists occasionally succeed in conveying the richness and complexity of black life, they are often left…restricted by the narrow scope of the media, which tends primarily to exploit those fragments of African American life that have meaning for, and resonate with, whites.” (Newkirk, 5) Interestingly, Newkirk’s borrowed Du Bois’ metaphor for her book about black journalists’ experience in mainstream news, Within the Veil: Black Journalists, White Media.

Today, the number of minority students who seek journalism training is still relatively small. The number of journalism students of color who seek or stay in journalism careers is paltry. In the last decade, multiple studies and memoirs by black journalists and their professional organizations report that black newsroom staffers frequently find their expertise discounted, their news judgment questioned, and their work unfairly evaluated. (NABJ, Newkirk, Nelson) And while a flagging economy and corporate restructuring has hurt reporters of all races, the decline in the number of black journalists has been particularly steep. (NABJ Journal, April 2002, pgs. 7-8)

journalists has been particularly steep. (NABJ Journal, April 2002, pgs. 7-8)

Today, as the world’s dominant military and cultural power, America is loved and loathed, treasured and terrorized. The news industry is being simultaneously squeezed by corporate mergers and consolidations, and fragmented by social dislocation and the uneven proliferation of new technologies that make it possible for the economic elites of say, Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire to have an instant news and communications with Anaheim, California.

On the other hand, many working and middle-class Americans are less likely to read any newspaper at all, and millions rely on alternative news sources, such as late-night comedians and talk-show hosts, and news outlets with an explicit religious or ideological bent. Where the newspaper industry was expanding 100 years ago, both circulation figures and network news ratings have been sliding for years now. (New York Times Magazine) The industry’s response to these pressures has been bad for newsroom diversity.

As [Tom] Rosensteil, co-author of the book, The Elements of Journalism and executive director of the Washington DC-based Project for Excellence in Journalism told the NABJ Journal. (Davis, p, eight) “You need to have African Americans bringing different perspectives to the newsroom. The basic problem at the moment is that the newspaper industry does not seem to be interested in building circulation, but instead interested in building profit….”

Washington DC-based Project for Excellence in Journalism told the NABJ Journal. (Davis, p, eight) “You need to have African Americans bringing different perspectives to the newsroom. The basic problem at the moment is that the newspaper industry does not seem to be interested in building circulation, but instead interested in building profit….”

Building circulation and building profit once were synonymous, but that’s no longer true. That’s partially because conglomerates now own many news organizations whose primary business is something else — and the earnings expectations are driven by the parent industry. So, Viacom, which owns the once-revered CBS News operation, expects its news operation to keep production costs down and ad revenue up. That mindset means such staples as investigative reporting and foreign reporting become luxury items. Reporting on poor neighborhoods and urban issues has been given short shrift as publishers chase advertiser-attractive suburban consumers.

In 2001, the highest-ranking African American in the newspaper industry, San Jose Mercury News publisher Jay Harris resigned to protest the industry’s devaluation of that larger social mission. Other respected veterans followed Harris’ lead. Sylvester Monroe, an assistant managing editor at the Mercury News, left the company in August, 2001 — ending 18 years as a staffer for nationally-recognized newspapers and magazines. Monroe told the NABJ Journal, “My decision to leave was not just about possible layoffs. It was about what the unrealistic profit targets set by Knight Ridder [owners of the Mercury-News and several other major metropolitian papers] was doing to the character and culture of the newsroom. I went from hiring 16 people to identifying people for potential layoff in less than one year.” Monroe is now writing a book about the personal price that he and other black members of his Harvard undergraduate class as a foot soldier for Ivy League integration.

(Dawkins, p.11)

Journalists generally, and minority journalists in particular, are trying to understand what it means to function in a post-modern cultural environment in which truth claims, personal identity and community structures are contingent and contested. I bring this up in contrast to Du Bois’ contention that African American identity is shaped by opposing forces of racism and resilience that, depending upon white America’s response, would to either renew or destroy the nation.

Du Bois’ biological and intellectual hybridity make him the embodiment of his argument about the centrality and value of African Americans in the American project. It is reasonable to infer that he would feel African American journalists are equipped to make an essential contribution to the achievement of the Hegelian self-consciousness that he felt that the achievement of a society’s democratic potential required. However, the increasing corporatization of news that Du Bois perceived decades ago, along with the emergence of postmodern culture, complicates the realization of Du Bois’ ideals.

One measure of the distance between the nascent modernism of the era in which Souls was written and our own time is consider, momentarily, how difficult it would be to infer how someone with Du Bois’ ancestry, upbringing and education would define himself today. Would he, as Du Bois did, see himself as fundamentally African and American? Would he be part of the ‘multiracial movement” that succeeded in forcing the US government to change its categories in the 2000 US census? Given his careful delineation of the African American class structure, would he necessarily see a connection between his own destiny and the future of the one-third of African Americans who, according to the most recent government figures, remain below the poverty line?

It would be madness to presume to know the answers, but the point here is that African Americans’ responses to these questions, and the larger society’s response to African Americans — are more complex now than it was 100 years ago. Even if a modern-day Du Bois did perceive racial inequality as an important issue that affected him personally, one cannot logically infer that he would assume that he bore some mantle of racial loyalty or responsibility as a result. He might find himself in agreement with African American Harvard University Law professor Randall Kennedy who contended in a 1997 article for the Atlantic Monthly that, “The fact that race matters, however, does not mean that the salience and consequences of racial distinctions are good or that race must continue to matter in the future. Nor does the brute sociological fact that race matters dictate what one’s response to that fact should be.” (Kennedy)

It would be madness to presume to know the answers, but the point here is that African Americans’ responses to these questions, and the larger society’s response to African Americans — are more complex now than it was 100 years ago. Even if a modern-day Du Bois did perceive racial inequality as an important issue that affected him personally, one cannot logically infer that he would assume that he bore some mantle of racial loyalty or responsibility as a result. He might find himself in agreement with African American Harvard University Law professor Randall Kennedy who contended in a 1997 article for the Atlantic Monthly that, “The fact that race matters, however, does not mean that the salience and consequences of racial distinctions are good or that race must continue to matter in the future. Nor does the brute sociological fact that race matters dictate what one’s response to that fact should be.” (Kennedy)

Kennedy, a Princeton, Yale and Oxford graduate whose siblings are also Ivy-League educated legal professionals, argued that it is unjust and unwise for African Americans to claim kinship, pride or responsibility on the basis of race. African Americans should strive, Kennedy said, for the abolition of racial distinctions. Privileged blacks bear no special responsibility for the advancement of social justice; that responsibility belongs to all Americans.

Finally, Du Bois and his peers were acutely aware that whether they wanted it or not, their views and actions would affect racial policy and politics. Frederick Douglass called for the abolition of racial categories, but he knew that his pronouncement would be viewed as a black leaders’ statement about the aspirations of black people. The generation of leaders that followed him at the turn of the century held conferences to debate the future of the race; these evolved into political, fraternal and civic organizations that became the infrastructure of the black bourgeoisie. Since integration, the tight web of black colleges, greek-letter organizations, secret societies and church networks has become more diffuse, and the charge to” be a credit to the race” is not as consistently heard. Today, while one can speak of blacks in leadership positions in the news industry and elsewhere, it is more difficult to predict what, if any, racial responsibilities they think they have.

To be sure, black journalists and their allies have made prodigious efforts to improve the depth and sophistication of news coverage of African Americans and others who have historically been underrepresented or misrepresented in the news, and there are notable achievements, such as Bryant Gumbel’s successful effort to broadcast NBC’s “Today” show from Africa for one week. What’s more, the presence of blacks and other journalists of color in mainstream newsrooms has sometimes resulted in ground-breaking efforts to confront racial issues — most notably, The New York Times’ series, “How Race is Lived in America.” However, for every success, there are tales of frustration over what continues to look like a failure to assign equal value to the lives of people of color.

To be sure, black journalists and their allies have made prodigious efforts to improve the depth and sophistication of news coverage of African Americans and others who have historically been underrepresented or misrepresented in the news, and there are notable achievements, such as Bryant Gumbel’s successful effort to broadcast NBC’s “Today” show from Africa for one week. What’s more, the presence of blacks and other journalists of color in mainstream newsrooms has sometimes resulted in ground-breaking efforts to confront racial issues — most notably, The New York Times’ series, “How Race is Lived in America.” However, for every success, there are tales of frustration over what continues to look like a failure to assign equal value to the lives of people of color.

As I write this, for example, daily headlines for the last three weeks have covered the disappearance of affluent Utah teenager Elizabeth Smart. According to noted Black Studies scholar Lenworth Gunther, more than 800 stories have run on Smart. At the same time, Alexis Patterson, an black girl who disappeared three weeks before Smart, has been featured in fewer than 100 stories. (Gunther) These and other examples demonstrate that much work remains if the stated goal of serving democracy by covering all communities fairly is to be realized.