This year marks the tenth anniversary of the publication of the Knight-Carnegie Initiative report on the Future of Journalism Education. A collaboration between two foundations and 11 prominent journalism schools and institutes, the initiative was formed in 2005 to address both long-standing concerns about the intellectual depth and breadth of journalism education and contemporary questions about how to add digital skills and entrepreneurship to the curriculum.

In 2007, I wrote my own short essay for Nieman Reports calling for a new approach to journalism education. I argued that, “The challenge for journalists—and journalism educators—is to think about ways to create dynamic curricula to enhance the practice of journalism. Such a challenge lends itself to the development of new and closer partnerships among journalists, technology specialists involved with communications tools, economists looking at new business models, and educators working with the next generation of potential journalists. ” Specifically, I called for:

- the creation of an undergraduate journalism education major and related certification that would support the teaching of media literacy and multimedia technology skills in secondary schools,

- the infusion of what has come to be known as computational thinking (the ability to formulate, analyze, and solve problems in ways that optimize what humans and computers do best) in our undergraduate and graduate curricula,

- an alertness to the ways in which emerging and evolving computing and communications technologies will reshape our industry. I urged journalism educators to engage in interdisciplinary research and teaching collaborations and called for attention to the likely impact of artificial intelligence on our news distribution and consumption practices.

Some of this seems obvious now. No one argues whether computational thinking is important or whether newsrooms need technologists and multimedia specialists, for example. Similarly, no one argues the need for greater media literacy to combat disinformation and to foster greater civic participation. Every journalism program understands the need for digital and multimedia faculty – and that big data and AI matter. Data journalism and interactive journalism are recognized occupational specialties, and a fertile area of scholarship (See Nikki Usher, C.W. Anderson). Something akin to the open source software movement is emerging among journalism educators focused on innovation, with texts on such urgent topics as media entrepreneurship, data journalism, coding pedagogy, and verification. And no one argues the need for the new forms of interdisciplinary collaboration and research partnerships.

Despite this, none of the articles in that Nieman special issue on Teaching Journalism in the Digital Age anticipated the degree to which the knowledge, values and skills required to deliver a 21st century journalism education require a fundamental rethinking of the requirements journalism educators should be expected to meet. What we are confronted with goes beyond the need to incorporate new specialties within the existing structure of journalism and mass communications departments. The transformation of our news and information ecosystems changes the nature of everything we do, and the contexts in which we do it.

We debate whether aspiring journalism educators actually need a PhD (and if so, in what?) , and how we should value professional experience, vs. academic credentials. We’re trying to get at the question of what all journalism educators should be expected to know, how specialties within the field can be defined, and come to conclusions about the academic and professional preparation best suited to the tasks.

The purpose of this essay is twofold: to instigate a conversation about areas of practice and pedagogy that are central to the challenges confronting us, and to highlight examples of work intended to confront these challenges. In particular, I want to focus on three areas that have been a focus of my own re-education over the last 30 years: journalism’s epistemologies, ontologies, and literacies. Ultimately, I hope this will inform our approach to designing curricula for graduate programs for journalism educators, and for thinking through strategies and standards for their ongoing professional development.

A bit about me: I’ve been teaching Journalism and Professional Writing for 30 years in a small undergraduate program. (We have a separate Communication Studies department with whom we work closely.) I came to academia with a background in science communications, corporate PR, and freelance magazine writing, During the 1980s, I witnessed the pervasive effects of hollowing out of the manufacturing economy. I was also part of a generation of people with minoritized identities (in my case, Black, female, a mother, urban, newly middle-class, newly disabled) who had gained entrée to spaces previously denied them (in my case, the Ivy League, the tech industry, affluent suburbs). I thought I might be able to help journalism and PR students understand what this emerging economy would look like and what it would demand of them.

I was also impelled by a larger set of public policy debates crystallized in a 1987 report by the US Department of Labor – Workforce 2000: Work and Workers for the 21st Century. Based on its demographic analysis, the report’s writers concluded that the America’s future required finding, cultivating and making space for people with backgrounds like mine. Specifically, it argued:

If the United States is to continue to prosper, policymakers must find ways to accomplish the following: stimulate balanced growth; accelerate productivity increase in service industries; maintain the dynamism of an aging workforce; reconcile the conflicting needs of women, work and families; integrate Black and Hispanic workers fully into the economy; and improve the educational preparation for all workers.

William B. Johnston et. al., https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED290887.pdf

I started teaching online journalism in 1996 and co-founded a department of Interactive Multimedia in 2003, partially hoping to create an environment for interdisciplinary learning and reflective practice. What I know about communications theory and journalism history beyond my Master’s degree is largely self-taught. What I know about programming, scripting, and design is either self-taught, a by-product of the eight years I spent at AT&T in the 1980s where even word processing required writing in Unix, or the product of two decades of research and teaching collaborations with computer scientists, media scholars and designers.

I do recognize that I am writing this at a time of existential crisis for journalism as a civic institution and as a financially viable industry. I’m also writing at a time when a global pandemic has accelerated and exacerbated threats to the existence of many colleges and universities. However, if democracy and civil society is to survive, some form of independent journalism must be part of the social contract. Whatever form that journalism takes, these questions will need to be addressed.

Challenge 1: Journalism’s epistemologies

How do we know what’s worth reporting and how do we get and vet what we report? These are essential questions that we attempt to address by hewing to a discipline of verification. The computational turn in journalism is the latest of a series of movements that can create more comprehensive, engaging, and more accurate reporting through the development and deployment of new tools for mining, analyzing and presenting information. It’s also a movement whose failings highlight the ways in which the news industry continues to grapple with unresolved historical rifts over objectivity, fairness, and the nature and needs of the publics journalists serve. And it’s empowered malign actors with tools to amplify violent ideologies, lies, and dangerous fringe ideas.

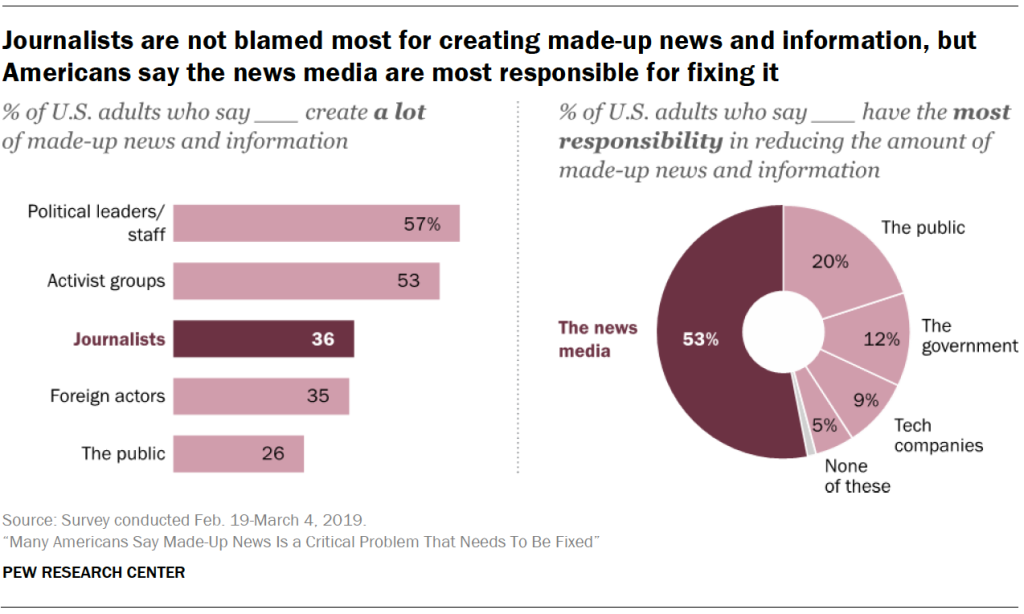

This June, 2019 Pew Research poll is just the latest of a long list of studies confirming that news consumers recognize the credibility crisis in journalism.

Writing in the Columbia Journalism Review, Avid Ovadya advances a framework for he calls the credibility assessment model: “In summary,” he writes, ‘the answer to the question ‘What should we investigate if we want to determine whether something is credible?’ is that we need to investigate the evidence supporting the claims, the reputation of the network purveying the information, or some combination of the two. Journalists have created a number of fact-checking and verification operations to guide news consumers to credible information, But the problems of fake news and public skepticism persist.

Computational journalist and educator Jonathan Stray notes that the strategies that governmental agencies, platforms and news organizations vary widely in their effectiveness in combating misinformation. The most effective strategies and tools may be incompatible with the values of a free press and free speech. In 2019 paper (.pdf) presented to an international conference on the issue, Stray argued, “In societies with a free press, there is no one with the power to direct all media outlets and platforms to refute or ignore or publish particular items, and it seems unlikely that people across different sectors of society would agree on what is disinformation and what is not.” You can see Stray’s presentation to an international conference on countering misinformation.

Ovadya hopes the framework that his team is developing will be used to create fact-checking systems that can be run by networks of bots on large data sets. But finding reliable measures of evidence and reputation that are free of implicit bias and accepted in a wide range of contexts is proving to be a wicked problem. As Cathy O’Neil notes in her book, Weapons of Math Destruction, data that appears unbiased is often anything but:

The models being used today are opaque, unregulated, and uncontestable, even when they’re wrong. Most troubling, they reinforce discrimination: If a poor student can’t get a loan because a lending model deems him too risky (by virtue of his zip code), he’s then cut off from the kind of education that could pull him out of poverty, and a vicious spiral ensues. Models are propping up the lucky and punishing the downtrodden, creating a “toxic cocktail for democracy.” Welcome to the dark side of Big Data.

Blurb for Cathy O’Neil’s Weapons of Math Destruction

While the definition of journalistic objectivity has never been stable, there’s no current consensus on what it means and whether it is attainable and desirable. David Mindich, Pamela Newkirk, Natalie Byfield and Lewis Raven-Wallace are among those who have persuasively argued that even in the good old days when journalism was more trusted, news organizations often failed to meet their own standards for credible sourcing, representative coverage and political independence. These failures, in large measure, were failures to accord epistemic authority to those on the less privileged side of the Robert Maynard’s “fault lines” of race, class, gender, geography and generation. (As Mark Dery has noted, this failure persisted has into the digital era.)

All journalism educators should be conversant with these debates and the evolving standards of practice that emerge from them. This especially applies to professors of the practice who might have absorbed the facile notion that the most objective reporting “plays it down the middle.”

Challenge 2: Journalism’s ontologies

Ontology is that branch of philosophy that seeks to name what “is” in the world. To say that in the past, journalists were gatekeepers is to make an ontological statement. So are definitional distinctions between “news,” “features,” “entertainment,” etc.

Similarly, In computer science, ontology refers to the act of defining the categories and hierarchies that are used to structure information in algorithms and databases. In a digital age, journalism’s ontologies are represented in both the human and technological structures of news ecosystems.

David Ryfe argues that the fundamental crisis facing American journalism in particular, and Western journalism, generally, is ontological:

Today, in the field they once dominated, journalists find themselves standing cheek by jowl with a vast array of other news producers: from community blogs to corporate communications offices, and from nonprofit organizations to advocacy groups. Many of these organizations have little interest in or knowledge of journalism. Yet, they produce and distribute as much if not more news as journalists.

In this context, the question of what journalism is, and is for, and how it is to be distinguished from an array of other news produces, is raised anew.

Ryfe, D. (2019). The ontology of journalism. Journalism, 20(1), 206–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/8756087918809246

One of the challenges to journalists’ efforts to convey those distinctions is that many members of the public they seek to serve don’t see journalists the way they see themselves. Brendan Nyhan and George Lakoff are among the researchers who have taught us that the simplest claims of fact can land differently with different audiences. To a disturbing degree, substantial percentages of Americans agree with former Pres. Donald Trump’s assertion that mainstream news organizations are the “enemy of the people.” Take the topline results of this August, 2018 Ipsos online poll, for example:

While a plurality – 46% — agree “most news outlets try their best to produce honest reporting”, there are very stark splits by the partisan identification of the respondent with most Democrats (68%) generally believing in the good intent of journalists, but comparatively few Republicans (29%). And when we ask questions with specific partisan cues, the political split is very wide. For instance, 80% of Republicans but only 23% of Democrats agree that “most news outlets have a liberal bias,” and 79% of Republicans but only 11% of Democrats agree, “the mainstream media treats President Trump unfairly”. Returning to President Trump’s views on the press, almost a third of the American people (29%) agree with the idea that “the news media is the enemy of the American people,” including a plurality of Republicans (48%).

Americans’ Views on the Media: Ipsos poll shows almost a third of the American people agree that the news media is the enemy, August 7, 2018. Accessed July 18, 2019. https://www.ipsos.com/en-us/news-polls/americans-views-media-2018-08-07

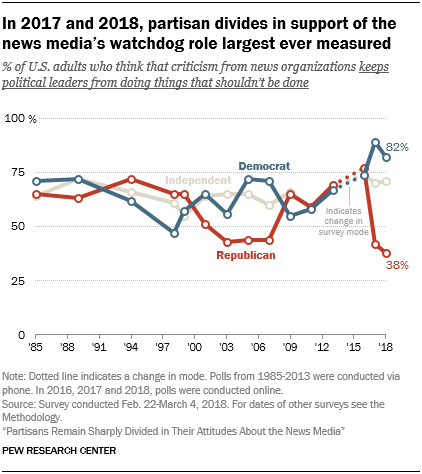

Similarly, public perceptions of the degree to which journalists fulfill such traditional roles as serving as watchdogs holding the powerful to account are divided along sharply partisan lines. This 2018 poll from Pew Research illustrates that division.

There’s a broad agreement that rebuilding trust in journalism requires finding new ways to connect with communities – and that requires developing products and approaches that respond to specific community needs. Monica Guzman offers this guide for engaging audiences. The Democracy Fund has engaged in a multi-year effort to identify best practices, tools and funding mechanisms for inclusive, community-driven journalism. Free Press offers guides to help communities and news organizations collaborate to improve news coverage.

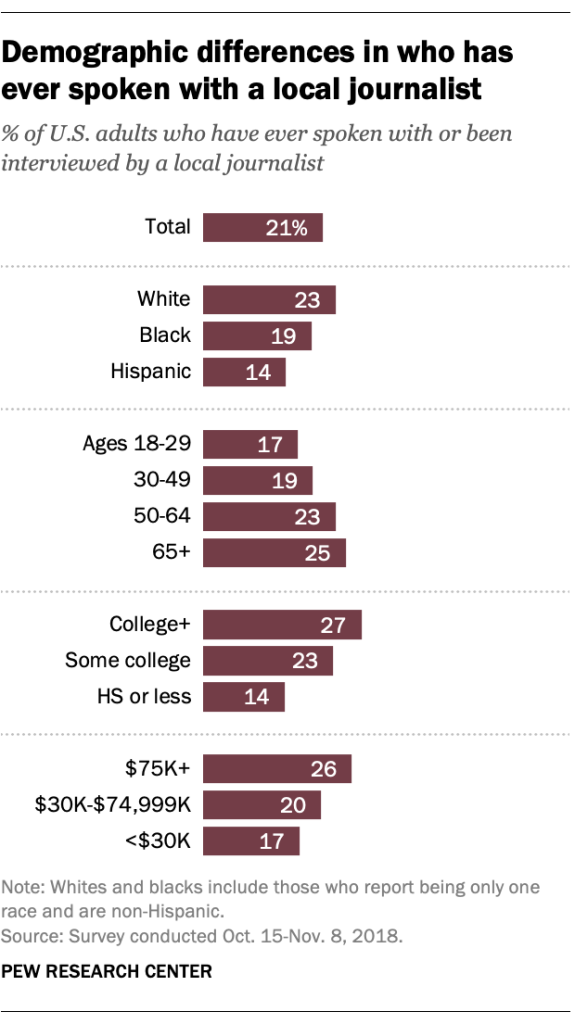

These efforts are as effective as the depth and breadth of the constituencies they engage. There is evidence that news organizations aren’t meeting that bar now. A May, 2019 Pew survey found that the people most likely to be interviewed by local news outlets are most likely to be older, educated, white men.

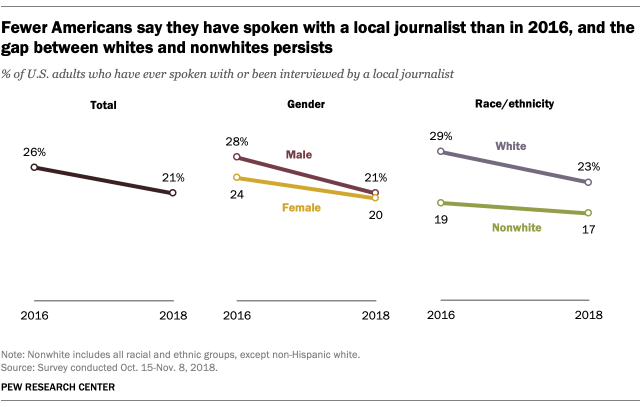

The same survey found that the percentage of Americans who had spoken to a local journalist declined between 2016 and 2019.

Sue Robinson has produced a guide for journalists seeking to diversify their sources, drawing upon research conducted in cities across the United States. Resource constraints are major issue, Robinson reports: “With contracting newsrooms, journalists of all colors find themselves stretched thin in reporting on local communities such that all voices and perspectives can be represented.” Noting that many members of marginalized communities have justifiable fears about opening up to the press, she calls for, “rethinking traditional journalistic notions such as “critical distance” and re-conceptualizing established relationships to sources and audiences so that source networks expand. ”

Similarly, improved reporting on rural America also requires a fundamental rethink. Letrell Deshan Crittenden and Andrea Wenzel underscored this in their April 2020 Tow Center report, The road to making small-town news more inclusive. Crittenden and Wenzel conducted focus group research in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, a rural community that New York Times columnist David Brooks depicted in a 2001 book as uniformly pastoral, conservative and white. But Chambersburg is diverse, and the lack of a common and inclusive local news source has reinforced racial divisions and impeded civic dialogue. Black and Latinx community members argued that news coverage of their community is either stereotypical or nonexistent, with deleterious consequences for local governance. White respondents downplayed racial tensions and decried perceived liberal media bias. Latinx participants called for more Spanish-language news sources.

This kind of qualitative research informs the movement to integrate design thinking into journalism practice and pedagogy. Design thinking can be a great entry point to developing and teaching strategies for more inclusive news reporting, presentation, and community-building. It also opens the door to deeper questions about the affordances and limits of the technologies at our disposal. Computer scientist Ramesh Srinavasan has argued that if we approach the development of information technologies with cultural humility, our databases and content management systems might be reimagined to reflect how the communities we are designing for create and preserve knowledge. Journalists, designers and computer science ought to be in collaborative conversation about the ideas that Srinivasan is advancing. You can learn more by reading the summaries of his projects and the elaboration of his ideas in his books as Whose Global Village? , After the Internet, and Beyond the Valley.

Challenge 3: Journalism’s literacies

In a 2018 Nieman Reports essay, Cindy Royal, a leading scholar and curriculum developer in the area of coding pedagogy for journalism, argues persuasively that too many journalism faculty resist learning and teaching the skills students need to meet employers’ growing needs. Royal notes a 2018 study by Amanda Bright documenting this bottleneck, and noting that innovation, to the degree that it is happening, is concentrated in larger, better funded programs. Royal calls for the inclusion of digital technology design and development in Communications PhD curricula and a reworking of institutional recruitment, tenure, and promotion practices to place greater value on teaching, research and practice in these emerging critical areas. In a separate Nieman essay she argues that, at the very least, every journalism faculty member needs to know how to teach some fundamental technical skills, such as how to scrape a website.

Mindy McAdams agrees. McAdams is a pioneer in online journalism practice and teaching who has influenced thousands of online journalists with her workshops, blog posts and books. In an October, 2019 telephone interview, she observed that too many journalism educators who don’t consider themselves technology specialists “think they don’t need to know about the tech.”

“I feel like if you are In the field of chemistry you take it upon yourself to know what’s happening in the whole field,” McAdams said. For example, “As AI becomes such a buzzword, how many people who are journalism educators even know what is meant by that? They could know more about it if they follow it as a news topic.”

Royal created CodeActually, a coding curriculum for journalism and communications students. And if you are baffled by AI, McAdams has a helpful lecture series on YouTube, AI in Media and Society, that will bring you up to speed.

My own thinking about what Royal and McAdams are saying is “yes, and.” The technological transformation of news gathering has changed every aspect of journalism practice, and I can’t conceive of an aspect of the curriculum that can be taught without rethinking tech’s role. That role is more profound than I realized back in 2009, when I argued that journalists needed to understand computational thinking.

But I’ve come to the conclusion that knowing how technology affects what journalists can do and how that’s received is more important than knowing how to “do” the technology. And it’s equally important to understand what the technologies, and the thinking behind them, do – especially to people and communities in information deserts or who are targets of disinformation. (This reading list necessarily starts with Meredith Broussard’s Artificial Unintelligence, but we need journalism-relevant analyses of the work of Simone Browne, Cathy Davidson, Safiya Noble, Ruha Benjamin, Virginia Eubanks,, Mar Hicks, and Andre Brock, for starters.

Here are four examples that might give pause to faculty who think that their teaching and practice are unaffected by technological change :

Journalists have had to rethink the inverted pyramid in light of research on the impact of linguistic framing. Journalists’ assumption that audiences trust a dispassionate recitation of facts in perceived order of importance is no match for a media ecosystem dominated by social platforms that make it easy to publish and amplify all kinds of misinformation and disinformation. That’s why linguist George Lakoff advises that journalists substitute the “truth sandwich” for stories about lies and misinformation:

Truth Sandwich:

1. Start with the truth. The first frame gets the advantage.

2. Indicate the lie. Avoid amplifying the specific language if possible.

3. Return to the truth. Always repeat truths more than lies.

Hear more in Ep 14 of FrameLab w/@gilduran76

Originally tweeted by George Lakoff (@GeorgeLakoff) on December 1, 2018.

Lakoff’s recommendation is grounded in his decades of work in linguistics, cognition and neuroscience. This video provides a helpful introduction.

Our audience engagement strategies and technologies aren’t value neutral. Journalism practitioners, educators and scholars need to be able to engage the questions Andrew Losowsky and Jennifer Brandel raised in their session on audience engagement ethics at the 2018 Online News Association conference:

‘Audience engagement’ is the hot new thing in journalism; but most journalists are pursuing it without understanding the risks – for the community and for the newsroom – of inviting the audience into a conversation. What happens when people who aren’t used to being sources share a sensitive, deeply personal story? What happens when we reach out to communities for information, but don’t stick around to answer questions or address concerns? How do we build trust authentically, without resorting to a journalistic sleight of hand to get reluctant sources to talk?

We urgently need to establish ethical frameworks around this work, or we risk further erosion of trust in journalism, and could even be endangering people’s lives.

Optimizing engagement tools to promote accurate information and constructive discourse is no mean feat. A March, 2019 article in Recode detailed Twitter’s stymied efforts to create incentives for constructive conversations on the platform. One fundamental challenge is understanding how to gauge the “health” of a conversation.

Technology has breached the church-state divide between the business and editorial sides of news in subtle and overt ways. The Columbia Journalism Review has argued that journalists need to understand how advertising technologies “influence the practice, distribution, and perception of journalism.”

Efforts to assess address the information needs of underserved communities can be facilitated or impeded by the way we deploy audience engagement technologies and related strategies. For example, Sue Robinson studied how mainstream journalists’ narrow sourcing and reliance on social media posts to gauge African American community views of a charter school controversy in Madison Wisconsin contributed to important blind spots in their reporting. She notes, “Despite the optimism that digital networks will diffuse power through entrenched structures, scholarly evidence has shown how online networks act as echo chambers for the powerful. In these spaces, offline inequalities not only persist but are exacerbated in digital spaces,”

We need to analyze journalism technologies and storytelling methods through the lens of critical computing. In his 2013 book Phantasmal Media: An Approach to Imagination, Computation and Expression, D. Fox Harrell explains that

“[C]ritical computing entails critically assessing the potential of the technology being researched and developed to engender conceptual change in users and the potential of the technology to engender real-world change in society….. Critical computing systems are built on cultural computing groundings, which in turn are informed by subjective computing research aims.”

D, Fox Harrell

Because those subjective aims can reinforce oppressive systems, Harrell stresses the importance of bringing diverse perspectives to the tech development process. As we embrace various dynamic storytelling tools for journalism – augmented reality, virtual reality and gamification, for example – we need to be cognizant of these cultural groundings and subjective aims, and we need well-researched pedagogies that address them.

Those pedagogies need to address not only how we tell individual stories in an ethical, accessible and inclusive way, but also how we help members of vulnerable communities harden their media ecosystems against propaganda and disinformation. For example, Howard University’s Truth Be Told News project has been combatting misinformation in and about African Americans for years in the tradition of the historic Black press. But it’s unlikely that the project’s creators ever envisioned the troll-powered Russian disinformation campaigns unleashed on social media in 2016 and 2020 to discourage African Americans and Latinx voters from participating in the electoral process. In December, 2020, Facebook and the National Association of Black Journalists launched a Fact-checking Fellowship that will fund journalists for one year’s work with an established fact-checking outfit. It would be wonderful if there were parallel initiatives supporting basic research on these issues at institutions such as Howard that are deeply connected to the communities being targeted. At the University of Buffalo, Siwei Lyu is doing NSF-funded research on helping people and systems detect deepfakes. Computational journalists need to be part of these research projects.

Conclusion

It’s hard to think about what journalism educators will need to know when we don’t know what journalism will become. Nic Neumann’s January 2021 report on journalism’s trends and predictions for the Reuters Institute identifies far-reaching changes in editorial practices and business structure:

2021 will be a year of profound and rapid digital change following the shock delivered by Covid-19. Lockdowns and other restrictions have broken old habits and created new ones, but it is only this year that we’ll discover how fundamental those changes have been. While many of us crave a return to ‘normal’, the reality is likely to be different as we emerge warily into a world where the physical and virtual coexist in new ways.

Nic Neumann, Journalism, media, and technology trends and predictions 2021

However, we do know that the survival of democratic civic values requires a cadre of educators and leaders who can serve as advocates, defenders and innovators of the best that journalism has to offer. This will require more robust research and debate that goes beyond the “Do you need a PhD?” debate.

A 21st-century journalism department or school requires faculty with newsroom experience and expertise in the rhetorical and literary forms underpinning storytelling across platforms and in social environments. (Yes, that means writing and shoe-leather reporting skills are still necessary. They’re just no longer sufficient.) It also requires both data journalists and computational journalists who understand and adhere to principles of algorithmic justice. It needs social scientists who can teach the quantitative and qualitative skills needed to assess community information needs and translate those needs into reporting that will be seen as trustworthy and useful. It needs specialists in media psychology and ecology who are conversant with emerging technologies. It continues to need legal specialists and ethicists. It needs specialists in entrepreneurship and tech management, because news organizations are tech enterprises now. And it still needs historians – although the journalism history canon needs substantial revision and expansion. I don’t know of a Masters or Ph.D. program that does all of those things well. However, the areas I’ve outlined here may be a way of invigorating the imagination about what’s needed and what’s possible.