Dear Great-grandfather Jordan,

I wrote to you about eight years ago, around Independence Day, when it’s common to hear recitations of Frederick Douglass’ 1852 speech, “The Meaning of the Fourth of July to the Negro.” That speech was given some years before you were born enslaved in Devereux, Georgia. Mr. Douglass was speaking in Rochester, New York, and I doubt that his words reached your parents, Holland and Judy Priscella:

My subject, then, fellow-citizens, is American slavery.. I do not hesitate to declare, with all my soul, that the character and conduct of this nation never looked blacker to me than on this 4th of July!

Frederick Douglass

The headlines in 2018 have me thinking about the meaning of the citizenship that Douglass so casually claims here – a right he can assert because he escaped from his slavemaster. It’s a right that he knows he can lose, because under the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, it would have been legal for his former master to kidnap him back into bondage.I’m thinking about Douglass and you because there’s been talk in the news about rescinding or reinterpreting part of the 14th Amendment to the US Constitution – the part that accords citizenship to anyone born on US soil, with a few narrow exceptions.

It was the 13th Amendment that made your enslavement illegal, the 14th Amendment that gave you citizenship, and the 15th Amendment that gave you the theoretical right to vote. Of course, it took almost another century to make that last right real. Now, it seems some people think some parts of those measures should be up for debate.

The last time I wrote, I told you how I learned about you from an off-hand comment from my dad, your grandson, as we watched the TV miniseries Roots. We watched Kunta Kinte get beaten for not using his slave name and we saw him get his foot chopped off for running away, and my dad quietly said, “My grandfather talked about that.” I told you how older relatives told me you and your sister Elsie talked about beatings and everybody being forced to eat from horse troughs. Cousin Mel told me that you said the Master beat your daddy in front of all of the slaves “to show how it was going to go.” And they also told me about the camp meetings, and the singing and dancing on the holidays, how, when word came that Civil War was over, everyone was singing and shouting, “We are free!”

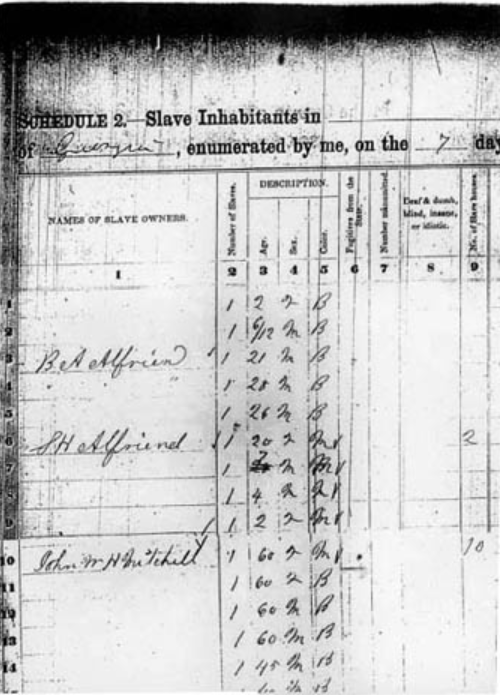

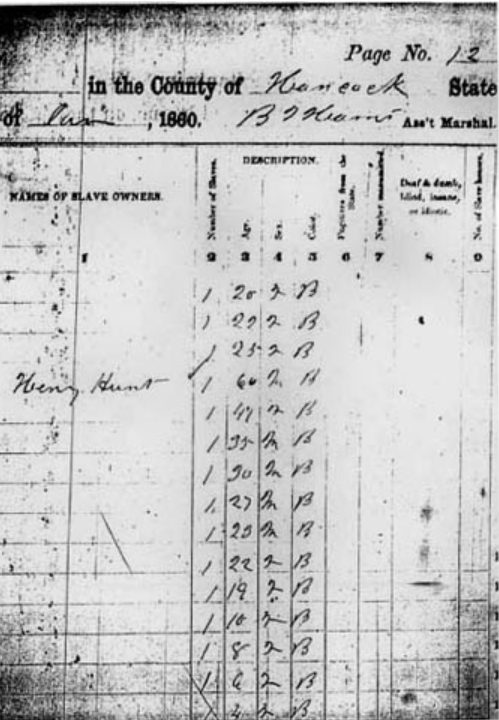

And I told how I went to Princeton University library, where I was an undergraduate, searched the 1860 Slave census and found an inventory of slaves of one John HW Mitchell. It was Cousin Ella who confirmed she had heard tell of that name. All these years since, I can’t look at those records without wanting to cry.

An excerpt of the slave rolls for John HW Mitchell in the 1860 census

The last of JWH Mitchell’s listed slaves.

Being a child of the Civil Rights era, I had already come to Princeton with a commitment to the struggle for human rights. That document further galvanized that commitment, because it told me that the nation that Francis Scott Key dubbed the “Land of the free and the home of the brave” only took notice of our family as your “owner’s” inventory – and even that wasn’t worth the trouble of listing you by name. If you were fortunate and they hadn’t been sold away, your parents, brothers and sisters were in that document, but your relationships to each other were not important enough to note. And let’s not even mention your forebears. I measure the value of my own work by the extent to which I help people see the insidious consequences of defining human beings as mere commodities to be bought and sold.

The precariousness of your family bond was underscored for me by a document from 1795 recorded in Lois Helmers’ compilation, “Early Records of Hancock County, Georgia.” In that document, one Daniel Richardson declares that :

[O]wing to the natural love and affection which I have unto my beloved daughter, Polly Thomas…I have given my negro woman Jenny and her increase… one boy named Tom and a girl named Malinda…”

Lois Helmers

Any “natural love and affection” Jenny might have had was not worth noting, of course. That’s the way it was. They could tear you away from your family to provide for their own.You and your family do show up in the 1870 census, and your father is in the Returns of Qualified Voters, Reconstruction Oath books 1867-79. In the 1870 census, you are listed as being 10 years old having the occupation of “farm laborer.” It says your dad was 58 and your mother 45, and they had both been born in Georgia. The box for parents of foreign birth is unchecked. And thanks to the 14th Amendment to the US Constitution, the box “Male citizens of US 21 years and upwards is checked. It also says none of you had attended school in the previous year, nor could you read or write.

There’s an 1882 marriage record for a “Jerdan” Mitchell and a “Mittie” Holsey which may belong to you and your wife, Martha. The 1900 census says you gave the year of your marriage as 1883, and Cousins Ronald and Eva said there’s a framed copy of your marriage license somewhere with the 1883 date, although I’ve never seen it and my cousins are with you now. But Ronald did say that it was a point of pride for you and the family that you were legally wed. Apart from religious sanction, being married theoretically gave you the rights of a patriarch – something your father didn’t have.

The 1920 census records your younger children starting to attend school. It looks as though Mattie – your daughter and my grandmother — got the farthest, which was 6th grade. For a time, she and her husband owned a house. From being property to owning property in one generation. She sold it after he died in 1959. She died during my first semester at Princeton.

These things all became legally possible because of those Constitutional amendments rendered you and your descendants legal persons, and that provided the foundation for the decades of litigation and protests it took to get laws and enforcement mechanisms to make the promise of citizenship real.

Your grandchildren were part of those protests. It’s what made it possible for a black man to be President, and for a black woman to have a chance at becoming Governor of Georgia. I think you might have an idea how much excitement that created – and how much anxiety, too. You were a teenager when black men were elected to state and local office during Reconstruction, but by the time you were in your early 30s, Jim Crow law undid those gains. A black man who got ahead in business or who demanded fair wages risked lynching. During the time we had a black President, threats against his life and that of his family were a constant worry. In the two years since he left office, hate crimes have been on the rise.

Southern violence was part of what motivated you and your wife to join your children and their families in New Jersey in the 1920s. Once there, you all found the same battles in a different guise. So I was raised with an awareness of the need for both hope and vigilance.

The people who want to repeal birthright citizenship say they are targeting the children of unauthorized immigrants – that in fact, they want to return the 14th Amendment to what they see as its original intent – granting citizenship to the formerly enslaved and their descendants. I wonder what you would say about that if you knew about the 2015 Supreme Court decision, Shelby County v. Holder, that undid a key provision of the Voting Rights Act. Ever since, lawsuits and charges of voter suppression have been on the rise. In Hancock County in 2016, sheriffs went door to door threatening to take away people’s right to vote unless they came to the courthouse and proved that their addresses were valid. One of the people quoted in the newspaper talking about it had the last name of Warren, same as the family your daughter Melvina married into.

You lived through the Second World War, so you saw what happened when Germany decided to take citizenship away from millions of its people – including the grandparents of my friend Tamar. It was a prelude to the Holocaust. Tamar’s mother came to this country as a refugee from Nazi Germany. She was naturalized and she married an American, so Tamar is a citizen by birthright. Our family histories have impressed upon us the fact that our rights are only as secure as our willingness to defend them.

I suspect, Grandpa, that birthright citizenship is the one thing that you were hoping that your family could count on. It was the foundation for getting voting rights, access to education, the means to earn more than a subsistence living. It’s still the foundation for the legal struggle to protect those rights – and to address other disparities under the law. If I understand anything about your legacy, Grandpa, it’s that I need to use the education that your struggle made possible to ensure that we never lose sight of what it took for you to become a legal person – and how easily those rights could all be undone if we lack the will to protect them.

With love,

Kim