Hi Mommy,

You and my father married in a double wedding ceremony with his brother and your cousin. It was an outdoor wedding, and from the one picture I have seen of you and your fellow bride, it was pretty and summer-casual. Your sister showed me the picture; she said there weren’t many. I have never seen a picture of you and Dad together when you were a couple.

Dad comes from a big family that was as well known in that part of South Jersey as yours. He’s the 7th of 12 kids born to parents who had left sharecropping in Georgia to come to New Jersey. His parents’ parents had been slaves, and his maternal grandparents had also come to Jersey, along with several members of their generation. So Dad had grown up in the bosom of a huge extended family that stretched across Camden County to Philadelphia and as far out as Pottstown and Phoenixville. They were their own village — not much need to spend time with strangers, until it came time to do business or find a suitable mate.

This is what you and Dad had in common: a belief in the value of work, and a desire to make the best of whatever you were given. Dad’s family had come through the Depression logging the Jersey pines, becoming trusted caretakers for local businesses owned by merchants who lived in the big city. doing day work, or whatever came along. Your family, too, was good at finding whatever work there was to be had. Both families took pride in rejecting welfare, no matter how tough the times got. (Not that welfare was all that easy for black families to get in those days, but that is another story.)

So you had those things in common. Also, among your peers, you were unique in having been Someplace Else. Well you were unique among the girls. Dad had been to Kentucky when he was in the Army. His brothers had been to the Pacific theater during and after the Big War. Living someplace else let you know something else was out there. But how to get to it? And what kind of dreams could a young Negro couple have anyway? Especially one where the husband was clearly too dark to pass for anything else?

This last point made your father-in-law skeptical, you told me. Then again, Grandpop Jesse was a tough man. Thirty-five years of hard work and no-nonsense family leadership had made it possible for him to own his own home and enough land to allow the family to grow much of its own food. I think you must have looked a little soft to him. Jesse Albert Pearson came from field slaves; your olive skin and curly hair told him that your family had worked in the Big House. And as far as you knew, he was right. You told me about forbears who had been cooks and chauffeurs in Virginia and Maryland and more recently, among the big houses on Philadelphia’s Main Line. Slavery was not part of your family’s story, as far as you knew.

You and my Dad shared a house with your cousin and her husband. The two brothers worked construction, until eventually Daddy got on at the Post Office. There were arguments about things like muddy boots being left on clean kitchen floors. Before long, both brides were pregnant, and the little house could not contain all the hopes and fears and tears and excitement and anguish.

Which is to say that neither marriage worked out, but babies were born and they were much loved. The second of those babies was me.

Here is what you told me about me before I was born.

First, I made you sick. You puked for seven months. Sorry about that. Scary thing for the girl that you were, no doubt. Perhaps a midwife could have told you that trick about eating plain yogurt before meals to dampen the nausea. In any event, with so many of the women around you seeming to have an easier time being pregnant, I got the impression that your sickness made you feel even more alone – a loneliness your husband was at a loss to understand.

Second, you didn’t have a nice maternity wardrobe. On TV, a pregnant Lucy Ricardo got to wear cute smocks — with big Peter Pan collars and dainty bows that matched the bows she would wear in her hair — while a bewildered but adoring Ricky tried to respond to her cravings and mood swings. In Chesilhurst, pregnant women wore their husbands’ pants and shirts used pots to boil their baby bottles, not expensive sterilizers. You tried to adjust.

Your father-in-law tested your mettle. You told me that on one Sunday visit while you were pregnant, he called you to the backyard for a chat. You don’t remember what it was about, but in those days, when an elder called you, you came. He had a freshly-killed hog hanging from a tree, and he was just beginning to butcher it. While he chatted amiably, he plunged a big knife into the hog’s belly and dragged it down to expose the entrails. Nauseous already, the hog’s reeking innards were about to make you swoon. As you fought to look attentive and keep from puking, your mother-in-law bustled out, alarmed! “Jesse!” she cried. “You can’t talk to Anna while you do that! The baby will have the face of a hog!”

When I was born, you told me Grandmom Mattie inspected my face to assure herself that it was quite human. (When you told me this story I was in my 30s and Grandmom Mattie had been dead for a while. I took some comfort in remembering that she had told me I was pretty.)

The only other thing I know about the circumstances of my birth was that I came at 6:30 in the morning, and my father had already gone to work. I tried to come out while you were in the hospital elevator, and a nurse put a hand on my emerging head to try to hold me back. She yelled , “Stop that! It’s not time yet!” And you said, “I can’t!” and soon after, when you reached the delivery room, I was born. Six pounds, three ounces, but the lungs weren’t in such good shape and you said one foot was curled into a club, but I think you must have been mistaken about that, because no one else remembers it and that just doesn’t go away from wearing orthopedic shoes.

The important part is that I was here, and eventually my lungs got better, but your marriage didn’t.

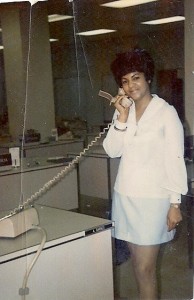

The two of you split and I was moved around between Dad’s relatives and yours while you each saved up money to make separate homes for me. Eventually, you got an apartment in a Camden rowhouse and an office job, most likely because they thought you were Italian and not Negro. I came to live with you, visiting Daddy and his new wife in Philadelphia on the weekends.

The thing that I want to thank you for the most is that you never talked badly about each other in front of me. And although there were many rocky times in the half-century to come, the two of you managed to support me through the triumphs and tragedies of my life. For this, I will always be grateful.

I love you, Mommy. Talk to you again soon.

Love,

Kim