The Re-education of Me Table of Contents

- What we investigate is linked to who we are

- The Me nobody knew then

- Mrs. Jefferson’s “Sympathetic Touch” meets Mrs. Masterman’s Philanthropy

- Discovering Masterman, discovering myself

- The electronic music lab at Masterman School

- The Interactive Journalism Institute for Middle Schoolers and the quest for computing diversity

Phliadelphia: 1963-67

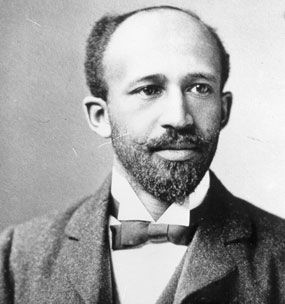

Literary scholars of the Freudian sort sometimes speak of the fantasmatic, a kind of archetypal drama etched into a writer’s subconscious, rooted in childhood experience, that finds expression in the structural elements of that writer’s work. In her groundbreaking 1998 tome, Psychoanalysis and Black Novels, Claudia Tate (pictured below, left) used to concept to explain WEB DuBois’ penchant for eroticizing the quest for freedom in his creative writing. I recall a conversation with Tate not long after the book was published in which we speculated that writers would probably do well not to dig too deeply into the oedipal roots of their creations.

I recall a conversation with Tate not long after the book was published in which we speculated that writers would probably do well not to dig too deeply into the oedipal roots of their creations.

Nevertheless, this work would be incomplete without some exploration of the ways in which personal experience and social location helped shape my way of doing journalism and thinking about journalism education. Research related to the effort to enlarge and diversify the computing pipeline discloses that young people’s career choices are heavily influenced by parents, teachers and guidance counselors. (References) In plumbing my childhood experiences, I see evidence how I began to think of myself as a writer, and the values I began to internalize that would shape the kind of writer I ultimately became.

Investigative journalist Florence George Graves alluded to the impact of the personal on the professional in her May 2003 Columbia Journalism Review essay, “The Connection: What We Investigate Is Linked to Who We Are.”(.pdf) Graves speculates that her penchant for uncovering secrets was probably affected by the coded rituals of segregated life in the Waco Texas of her childhood,

“I couldn’t stop wondering about certain aspects of life in Texas. Why were there separate drinking fountains for “whites” and “coloreds” in public places? Why did my close friend’s parents treat her decision to marry a Catholic as if there had been a death in the family? Why weren’t Jews allowed to join the country club? Why should girls bother to excel in school if they were not entitled to use their knowledge in the world beyond the home?”

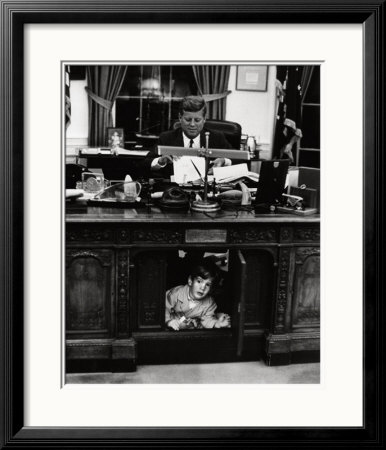

I was born in 1957 – the year of revolution in Ghana, federally-enforced integration in Little Rock, and the first human foray into outer space – accomplished by a Soviet regime considered the West’s chief global adversary. It was, in other words, a time when old orders were under siege, new power equations were being drawn and no one seemed sure whether the future held hope or annihilation. My childhood was lived in the space between the restrictive past and future possibility. On one occasion, my parents and I stood in one long line at an armory to receive a vaccine-laced sugar cube that promised protection against polio. On another, we stood in another long line to see the desk and other effects that had belonged to Pres. John F. Kennedy, who had been murdered in a Dallas street while I sat in my first-grade class and made a paper turkey to decorate our Thanksgiving table.

Unlike Graves, the adults around me openly discussed the reasons behind the inequalities that she observed in silence. The questions revolved around how those inequalities might be eliminated – or at the very least, how their destructive impact might be minimized. Racial justice and the quest for enlightened governance had been matters of vital concern in Philadelphia since the 18th century, when the Quakers debated the morality of slavery, and black freemen Richard Allen and Absalom Jones protested segregation within the Philadelphia Methodist conference by founding the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

From a sociologist’s perspective, I suppose my family’s prospects seemed fairly fixed in 1957. My paternal grandparents had been part of the Great Migration of African Americans from the Jim Crow south to the de facto segregated north. Their parents had been slaves. The men in my family mostly worked with their hands, mostly in construction. My father had done that kind of work as well, although by the time I started school, he had landed at the Post Office, and there he saw other black men who were going to college. With the help of his veteran’s benefits, he enrolled first in trade school, and then Temple University, fitting his classes around his swing shifts at work.

We weren’t the kind of people whose lives and concerns took up much space in the daily newspaper. The scholar VP Franklin (pictured, left) notes WEB Du Bois’ pointed critique of American journalism as he experienced it in the 19th and 20th centuries:

We weren’t the kind of people whose lives and concerns took up much space in the daily newspaper. The scholar VP Franklin (pictured, left) notes WEB Du Bois’ pointed critique of American journalism as he experienced it in the 19th and 20th centuries:

“The American press in the past almost entirely ignored Negroes. Very little of what Negroes wanted to know about themselves, their group action, and their relationship to public occurrences to their interests was treated by the press. Then came the time when the American press so far as the Negro was concerned was interested in the Negro as minstrel, a joke, a subject of caricature. He became, in time, an awful example of democracy gone wrong, of crimes and various monstrous acts.” (Franklin)

Philadelphia, where I spent most of my childhood, was no exception to this general rule. In her 2008 doctoral dissertation, communications historian Nicole Maurantonio supplied the scholarly support for the sense of invisibility and alienation that I and so many others experienced as we searched for some reflection of our reality in the Philadelphia newspapers. Maurantonio argues that in the years between the end of World War II and the fatal 1985 attack on the headquarters of the radical group MOVE:

“[N]ews organizations were not merely impartial storytellers providing a language with which to narrate crises. Journalists inscribed a rhetoric of racial marginalization that shaped discourses surrounding race and ‘radicalism’ within the city.”

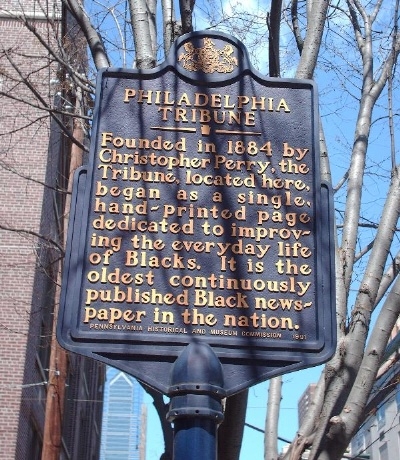

It was of course, the black press who tried to cater to the needs of African Americans in those years. From the time of its founding in the early 19th century, the black press had, as scholar Matthew Holden puts it, “facilitated the umbrella issues of freedom, racial uplift and the emancipation of the slaves.” My family, and most my peers regularly read the Philadelphia Tribune (which billed itself as “The Constructive Newspaper” in those days) and Ebony magazine alongside the Philadelphia Bulletin. Many of us listened to black radio stations, where DJs such as Georgie Woods (“The Guy With the Goods”) would become indispensable allies of the Civil Rights Movement.

Tribune (which billed itself as “The Constructive Newspaper” in those days) and Ebony magazine alongside the Philadelphia Bulletin. Many of us listened to black radio stations, where DJs such as Georgie Woods (“The Guy With the Goods”) would become indispensable allies of the Civil Rights Movement.

Maurantonio recounts how the Tribune tried to counter this dominant “rhetoric of marginalization” by calling for police restraint during such moments of crisis as the Columbia Avenue riot of 1964 – a series of violent clashes set off by false rumors that the police had killed a pregnant black woman. Maurantonio discusses the ways in which the Tribune and the other local newspapers framed their coverage in the following video segment (from 9:12 to 15:03):

My teachers created what I now recognize as a hidden curriculum designed to reinforce our belief in our own humanity in the face of segregationist school district policies and a a culture that, as Du Bois had explained decades before, constructed us as a problem. Between school, the neighborhood library where I discovered Carter G. Woodson’s magical Encyclopedia of Negro history, the devotion to learning that my parents modeled, I came to understand education as a pre-requisite for personal and racial advancement.

When my parents and teachers noted my curiosity about certain aspects of science and writing, they shepherded me into Saturday morning writing workshops and science classes. My stepmother folded lined paper into little booklets that I filled with short stories.

When I was 8, I appeared as a panelist on a children’s version of the popular College Bowl television quiz show. The show ran on WHYY, our local public television station, and was hosted by Philadelphia’s answer to Mr. Wizard, Bess Boggs. (At least that’s her name as i remember it; having failed to find a record of the show during my research, I’ve posted a Facebook query to fact-check my memory.) My parents dressed me in my Easter outfit for that year (a powder-blue tailleur with a faux-fur collar, don’t you know) and put my hair in a bob instead of the usual school-day pigtails. They cleared their work schedules to accompany me to the studio (no small feat, especially since my father worked swing shifts full time and went to school full time).

It will tell you something of who I was in those days to know that when Bess Boggs entered the studio, I jumped up and down and started tugging on my parents as if the Beatles and the entire Motown Revue had just strolled by. (Or maybe more – two years later, on a summer camp field trip, I was quite calm when we ran into Marvin Gaye in the Philadelphia International airport. It did please me mightily, of course, when he held my hand and planted a kiss on my cheek.) In any event, my admiration for Bess Boggs was in keeping with the fact that one of my other hobbies in those days was keeping journals on the Gemini space flights.

I don’t remember the show much, other than the fact that I was Kearny’s only representative. Kearny was not known for its academic prowess. The neighborhood it served included the Sunday Breakfast Mission, then at 6th and Vine. The tow-headed brother and sister in my class, the only white children in the school, if memory serves, were the missionaries’ children. They had transferred in from somewhere, and I don’t think they stayed long.

I don’t remember the show much, other than the fact that I was Kearny’s only representative. Kearny was not known for its academic prowess. The neighborhood it served included the Sunday Breakfast Mission, then at 6th and Vine. The tow-headed brother and sister in my class, the only white children in the school, if memory serves, were the missionaries’ children. They had transferred in from somewhere, and I don’t think they stayed long.

Kearny was old school. We lined up on the concrete playground by class in the morning and stood at attention in the stairwells once we were marched inside. Two or our more imposing teachers, Mrs. Jenkins and Mrs. McCoy, patrolled our ranks to ensure that we kept our mouths closed and our hands to ourselves while we awaited the class bell. Any transgression would require that you step out of line to have them smack you with a ruler. The school day began with a salute to the flag, the pledge of allegiance, and a moment of silent meditation. (We were told that the silent meditation was a substitute for the prayer that had been required until the Supreme Court banned the practice.)

My teachers exhorted us to be a credit to our race. A local historian, Ed Robinson, spoke at one of our assemblies about the glories of our African past. They were also steeped in art and culture – the crossing guard taught piano, and one of the teachers sang opera. One of the few white teachers taught us about Woody Guthrie and Huddie Ledbetter. They got us some instruments to start a small string ensemble, and had us learn two pieces for my one and only instrumental recital: an aria from Verdi’s “Aida” and “Go Down Moses.”

In Mrs. Moore’s class in second and third grade, I sat next to a handsome, sharply-dressed, husky-voiced and mischievous boy named William Cook. His brother, Wesley, who was three years older, was a fixture at the Friends’ Neighborhood Guild, whose library was one of my favorite haunts. My clearest memory of Wesley, whose neighborhood nickname was “Scout,” was of him sitting at a table at the Guild, telling another older boy, “Listen Up! Eli Whitney didn’t invent the cotton gin!” If I was 8 or 9, then, he was 11 or 12.

Two years after that, in November, 1967, after Wesley went to Stoddard-Fleischer Junior High School, we heard about the police cutting loose on a throng of high school and junior high school students who had gone down to school district administration building to petition for black history classes in the curriculum. We heard that Frank Rizzo, the inspector to whom mild-mannered George Fencl’s civil disobedience reported, had reportedly unleashed his men on the peaceful crowd with the command to, “Get their black asses!” (The year before, Time magazine had cited Fencl’s unit as an innovative way of managing protests with minimal conflict.) In later life, after he changed his name to Mumia Abu Jamal, embarked on a career as a journalist and activist, and ultimately landed on death row.

By the way, the city’s new superintendent of schools, Mark Shedd, earned the enmity of Fencl’s supervisor, Frank Rizzo, when he criticized the aggressiveness of police response to the demonstration, leading to Shedd’s ouster when Rizzo became mayor in 1971. In a subsequent section of this work, I will treat Shedd’s legacy in more detail, but for now, I merely want to note the controversy over the police action.

All of that would be later. Suffice it to say that by 1967, I had internalized my parents’ and teachers’ messages about the power of the pen, the fun and necessity of learning, and the certainty that Lord have mercy, we were moving on up!

Endnotes

- 1. Franklin, VP. “W.E.B. Du Bois as Journalist,” Journal of Negro Education, Vol. 56, No. 2 (1987). P. 240-244

- Philadelphia Tribune page one flag, Sept. 1, 1964

- For example, see: Cohoon, J. M. and W. Aspray, (eds.) Women and Information Technology: Research on Underrepresentation, The MIT Press, Cambridge MA, 2006; Barker, L. J., E. Snow, K. Garvin-Doxas, T. Weston, Recruiting Middle School Girls into IT: Data on Girls’ Perceptions and Experiences from a Mixed-Demographic Group, in Women and Information Technology: Research on Under-representation, Cohoon & Aspray, The MIT Press, Cambridge MA, 2006. pp113-136;

- References on the black press during this periodFor an on overview of the black press generally, see the PBS website for Stanley Nelson’s documentary: The Black Press: Soldiers Without Swords. Pamela Newkirk’s Within the Veil: Black Journalists, White Media (NYU Press, 2000) offers a comprehensive and concise overview of the process of integrating white newsrooms and its impact on the black press.