The Re-education of Me Table of Contents

- What we investigate is linked to who we are

- The Me nobody knew then

- Mrs. Jefferson’s “Sympathetic Touch” meets Mrs. Masterman’s Philanthropy

- Discovering Masterman, discovering myself

- The electronic music lab at Masterman School

- The Interactive Journalism Institute for Middle Schoolers and the quest for computing diversity

“There are, at least, two approaches to education: the mimetic approach and the mathetic approach. The mimetic approach emphasizes memorization and drill exercises and is most efficient in inculcating facts and developing basic skills [Gar89, p. 6]. The mathetic approach stresses learning by doing and self exploration; it encourages independent and creative thinking [Pap80, p. 120]. In the mimetic framework, creativity comes after the mastery of basic skills. On the other hand, proponents of the mathetic school believe that self discovery is the best, if not the only, way to learn…”

Sugih Jamin, Associate Professor, EECS, University of Michigan

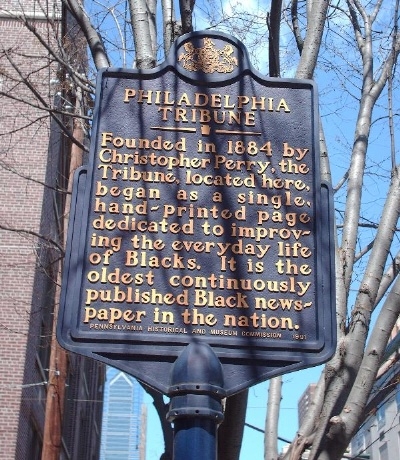

“Music educators can no longer ignore the possibilities afforded by computers and the related fields of science and mathematics.” With those words, Virginia Hagemann threw down the gauntlet to her colleagues in a 1968 essay for the Music Education Journal. It was the first of two articles she would write about the electronic music laboratory that she created at the JR Masterman Laboratory and Demonstration School in Philadelphia in the late 1960s.

I was a participant in that lab, and as I read Ms. Hagemann’s essays, I was struck by the parallels between her arguments for the effectiveness of electronic music and a tool for expanding the horizons of secondary school students, and the research and findings from the Interactive Journalism Institute for Middle Schoolers, a National Science Foundation-funded project for which I served as a co-principal investigator. Like Ms. Hagemann, we found that given the opportunity to make media, young people can produce artifacts that reflect fairly sophisticated concepts. We also concluded that professional development that empowers teachers is central to successful curricular innovation. Ms. Hagemann also learned serendipitously that a budding media maker is capable of becoming a technology innovator.

In this essay, I want to place Hagemann’s action research alongside the work of Seymour Papert and his intellectual descendants to turn computers into learning tools for children. While Hagemann was developing her ideas about electronics as a vehicle for musical composition and education, Papert and his colleagues at MIT were creating the LOGO programming language as a tool to help children construct their own knowledge about the world. With this foundation, he reasoned that teachers could then support students in moving to more formal understandings of concepts in mathematics, physics and other subjects that are generally considered abstract and difficult to learn.

Research shows that music education can be a wonderful foundation for teaching mathematics and by extension, computing.(Research on music and learning) The reasons are not hard to understand: both require that information be organized in certain structures. Pattern recognition is integral to both fields. Both have formal and informal “languages.” One can draw analogies between their elements – bits and bytes of computing and the diatonic scale in Western music, for example. Music has its own versions of computing’s “if-then” statements, loops, strings, recursion, modularization and other fundamentals. Both are fundamentally mathematical, although not necessarily in a “school math” kind of way. Looking back, I can see how many of these concepts were embedded in the work we did in Ms. Hagemann’s electronic music class.

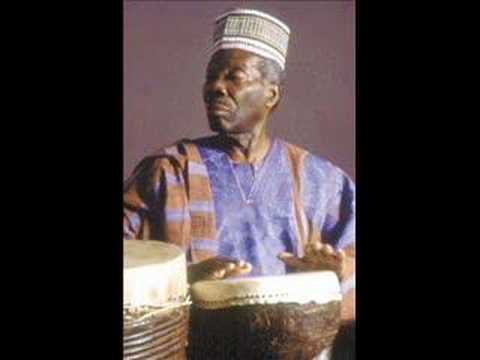

For the sake of context, I should mention that I also had traditional classes in basic music appreciation and theory while at Masterman, taught by Gloria Goode. Ms. Goode (as she was known then – she subsequently earned a doctorate) also expanded our cultural horizons. She added jazz, African and Brazilian music to our studies of Dvorak, Copeland and Stephen Foster. In sixth grade, we happened to have a student teacher who had lived in Brazil, so we learned to make their national dish, feijoada, and performed a Brazilian number in the school show. As one of the few black faculty members at Masterman, she was a powerful role model for the black students. She was also a crucial mentor for a small group of students who actually did become professional musicians in their adult lives. She also set an example for us as a life-long learner, sharing with us about her explorations of African music and dance, for example. Her 1990 doctoral dissertation, “Preachers of the word and singers of the Gospel: The ministry of women among nineteenth century African-Americans,” was hailed by the author Delores Causion Carpenter hailed as, “one of the finest treatments of 19th century black, singing, evangelist women” in her book, A Time for Honor: A Portrait of African American Clergywomen.

The exposure that she gave us to polyrhythms through the music of Babatunde Olatunji has particularly stayed with me. What follows is a video collection of the some of the music I was exposed to in Ms. Goode’s classes. I believe that what she taught me about the underlying structure of these diverse kinds of music would become important in Ms. Hagemann’s class, and in my later thinking about writing and problem solving. This collection includes not only Olatunji, but also Sergio Mendes, “Largo” from Dvorak’s New World Symphony, the folk song, “Goober Peas,” Della Reese and Wes Montgomery playing “Windy.” The last song especially sticks out in my mind because my first hearing of the song wasn’t Montgomery’s guitar version. It was our fifth-grade classmate Joel Bryant, who played the song for us on piano at her invitation at the end of class one day. Joel went on to become an accomplished professional songwriter, producer and accompanist with credits that include work with Philadelphia International Records and Gospel great Tramaine Hawkins. Joel was one of many professional musicians who came through Masterman.

Ms. Hagemann’s essays don’t explain what specifically prompted her to create an electronic music class, but she knew Robert Moog, the physicist-engineer whose experiments with the theremin led to his invention of the first popularly-used synthesizer in 1965. She was an active composer with far-flung connections who reportedly studied with the legendary music teacher Nadia Boulanger. (This assertion comes from a posting on Facebook; I am in the process of trying to verify it.)

What we do know from her 1968 essay, “Electronic Composition in the Junior High School,” is that she described the lab as “logical outgrowth and extension of the [Music Educators National Conference] Young Composers’ Project,” an initiative funded by the Ford Foundation. She started the lab with a $316 grant from a fund established by Philadelphia Schools Superintendent Mark Shedd for innovative teaching projects. According to Salon magazine, Moog synthesizers were $11,000 in those days, so she focused on components instead. We had two reel-to-reel tape recorders, an oscilloscope, sine and square wave generators, splicing equipment, and tools for making musique concrete, such as a gong and a metronome. We wrote our compositions on graph paper, plotting frequencies on the vertical axis and time on the horizontal.

According to Hagemann, the 15 children were initially selected to participate in the lab, and several dozen students were admitted into the program before long because of popular demand. All of the students who were initially selected played instruments. If my memory is correct, I entered the program during the 1968-69 school year, when I was in the sixth grade.

Ms. Hagemann’s methods emphasized the mathetic over the pedagogic or mimetic. Each of us was assigned a partner, which meant that we not only had the experience of composing and recording our own work, we also learned to play recording engineer for someone else. She exposed us to experimental composers and methods, and further broadened our cultural horizons. The video compilation below is a sampling of what we heard in class, and what we were taught to do. It includes Switched on Bach, Tibetan chants, a demonstration of musigue concrete composition and production techniques, and a Swingle Singers performance.

This early electronic music composition, “Lemon Drops,” by Kenneth Gaburo, was also part of our curriculum:

Hagemann cautioned her colleagues against being “guided by an outmoded philosophy that only the teacher knows best.” At the same time, she added,

“Although anything is possible, everything should not be permitted. In this incipient stage of a student’s musical development, the disciplined experi- ence of creating logical compositions within the frame- work of accepted musical form is imperative. Although students should become aware of the concept of alea- toric composition (eleven of the twenty-six members in the first class purchased John Cage’s book, Silence), the use of indeterminacy and chance elements in com- position should be reserved until the students have demonstrated their understanding of and competence to compose in various musical forms. Concurrent with a rigid adherence to traditional form, the children can be given a measure of freedom of expression to avoid stifling the possible creation and development of new musical structures.” (p. 88)

Hagemman reported surprise and delight at the quality and precocity of the musical compositions that emerged from the class (not from any of my work , though, I assure you!). But it was the technological innovation that took place that was an additional delight. She reports on page 90 that after field trips to Princeton and Philadelphia’s Franklin Institute:

“William Serad, age thirteen, submitted a technical report, complete with schematic diagrams, on the possibility of using an analog computer for writing electronic music. William thought that this computer would be useful in the writing of such compositions as “Study in Square Roots” or “Cube Root Canon.” His report was later discussed with Robert A. Moog, presi- dent of the R. A. Moog Company, Trumansburg, New York, manufacturers of electronic equipment, who agreed that this idea was feasible. With this encourage- ment, William constructed a four-sound, push-button switch, serial sequencer, which he used in writing an electronic canon. He has since made a working model of a tri-amplitude mixer module. Another member of the class, Randy Kaplan, age twelve, was inspired by the linear controller at Princeton to build a three- sound, push-button switch, serial sequencer with mixer. The teacher will not always understand every wire and transistor, but he can always tell if the equipment operates properly, and he can assist his students to use such devices musically.”

Hagemann concluded her article by noting that keeping up with her students had required her to embark on a new path of professional development for herself. She enrolled in an electronics course and started reading electronics reference texts. She picked up the theme of the necessity of teacher development in a Dec. 1969 article for the Music Education Journal, “Are Junior High School Students Ready for Electronic Music? Are Their Teachers?” Hagemann asserted that if teachers open their minds and become resourceful about using electronic music classes as a means of allowing students the “freedom to create” (.p 36) ,

“The adolescent need for independence will be satisfied by the creative freedom encouraged within the labora- tory. The study of the basic concepts of electronic music will help the student gain a critical perspective of himself, of his social environment, and of the ways he can shape new goals of learning.” (p.37)

I was astounded to read these words nearly 40 years later, because they are remarkably similar to the conclusions that we reached with regard to the results of our Interactive Journalism Institute for Middle Schoolers in exposing middle school students and teachers to computing and journalism as as means of creative expression and civic engagement. More about that in a future post.

Update: April 30 – Thanks to fellow Masterman alum and musician Ilene Weiss, who send these .mp3s from the online archives of Masterman student compositions on a Philadelphia radio station WFMU.

Music Educators Journal articles by Virginia Hagemann referred to in this post:

- Electronic Composition in the Junior High SchoolVirginia HagemannMusic Educators JournalVol. 55, No. 3 (Nov., 1968), pp. 86+88+90

(article consists of 3 pages)

Published by: MENC: The National Association for Music Education

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3392383

Are Junior High School Students Ready for Electronic Music? Are Their Teachers?

Music Educators Journal December 1969 vol. 56 no. 4 35-37

For examples of research on music and learning, see,

- Hetland, Lois, “Learning to Make Music Enhances Spatial Reasoning” Journal of Aesthetic EducationVol. 34, No. 3/4, Special Issue: The Arts and Academic Achievement: What the Evidence Shows (Autumn – Winter, 2000), pp. 179-238 (article consists of 60 pages) Published by: University of Illinois PressStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3333643

- Habib, Michel and Mireille Besson. “What Do Music Training and Musical Experience Teach Us about Brain Plasticity? Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal, Vol. 26, No. 3, Music and Language (Feb., 2009), pp. 279-285

- Wendy S. Boettcher, Sabrina S. Hahn, Gordon L. Shaw, Mathematics and Music: A Search for Insight into Higher Brain Function Mathematics and Music: A Search for Insight into Higher Brain Function,Leonardo Music Journal, Vol. 4, (1994), pp. 53-58

One of those “intellectual descendants,”, my colleague and collaborator Ursula Wolz, was researcher in Papert’s LOGO lab in the 1970s. In the early 1980s, she and Jim Dunne began teaching LOGO to children and teachers at Columbia Teachers’ College’s Microcomputer Resource Center. (See contemporaneous popular press reports on that work from Popular Mechanics and Infoworld. Wolz is the Principal Investigator of the IJIMS.

I thank my former Masterman schoolmate and academic colleague Elizabeth Gregory for her help in locating both of Ms. Hagemann’s articles.