Faculty and staff at New Jersey colleges protest stalled contract talks

-

On April 25th and 26th, employees and students at New Jersey’s public colleges held rallies protesting the lack of progress between state negotiators and unions representing faculty and staff at the various institutions. Most of the campus unions have been without a contract since July 1, 2011.

Why I put this post together

This post provides a round-up of news about last week’s protests, with commentary for context based on my 24 years of experience as either an adjunct or full-time faculty member. Academia is actually my second career. Prior to joining the TCNJ faculty, I was a lay counselor and writer for a comprehensive cancer center, and then a public relations writer for AT&T. I have also been a freelance magazine reporter and blogger. Although I am an AFT member and a TCNJ employee, these comments are my own.

I wanted to put this post together because I can remember how little I understood about what college faculty do before I became one. I completely understand why many people think we only work a few hours a week, for example, which couldn’t be farther from the truth. The hours in the classroom don’t count the time spent preparing for class, grading, advising students, writing recommendations, serving on committees, chairing departments or programs, advising student organizations, or networking on behalf our our students with employers and graduate schools. This is not a complaint – it’s an explanation.

I’ll also acknowledge that the respective state institutions vary widely in our mission and focus, and I can only speak about the institution where I work. I’ve never worked at a community college, where I hear of colleagues teaching 5 courses a semester. (I did that one semester, and considering that all of my classes are writing-intensive, I don’t recommend it.)

I’m a taxpayer too, and I’ve been a tuition-paying parent

I know the sticker shock associated with college costs. I’m still paying off my part of the loans that put my kids through school. I also paid my own way through graduate school. I know what it’s like to do that under the kind of duress that many workers experience – an unemployed spouse, health crises, single parenthood. I also know what it’s like to have to take on extra jobs to make ends meet.I also understand why there’s skepticism about the value of a college education, especially with the state of the national economy and tales of college graduates scrambling for minimum-wage jobs. My colleagues and I spend a lot of our time outside the classroom boning up on the changes in our respective fields and reviewing our curriculum, advising practices and career development resources so that our students and alumni have the best chance possible in an increasingly competitive market. Sabbaticals and career development funds help us do that. -

How do sabbaticals and career development funds for faculty benefit students?

Here’s an important quote from the first story in the list below that deserves comment: “[Gov. Chris] Christie has called for four-year salary freezes and an end to perks such as guaranteed sabbaticals, a staple of academic life, at the state’s nine nonresearch universities, which do not include Rutgers or the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, according to faculty union officials who have been involved in contract talks. You might wonder why “nonresearch” faculty would need sabbaticals.

It’s important to understand that although colleges such as mine are not designated as research institutions, we are required to do research in order to stay current in our fields so that we can be effective mentors and teachers to students. It’s called the “teacher-scholar” model – the idea is that our scholarship feeds our teaching, and our undergraduates get to be involved in research. Here is a 2007 report from the American Association of Colleges and Universities that does a good job of explaining the value of the teacher-scholar model. (http://aacu.org/liberaleducation/le-fa07/le_fa07_perspectives2.cfm) One difference between the description of the teacher-scholar model in the report and its implementation at our institution is that our undergrads work closely with faculty across the campus – not just in the sciences.Doing scholarship requires not only that we publish, but that we join the learned societies in our field (often at our own expense), present at conferences (again, often at our own expense or with limited support from our departments, because there just isn’t enough money to go around.)We take on the responsibility of securing grant funding for much of that research, as well as for needed improvements to labs, equipment and curricula. Going after grants is a lot of work for both faculty and staff, and there is no guarantee of success, but it’s worthwhile. However, many funders look for signs of institutional commitment in considering funding proposals. Here is a sampling of funded proposals that TCNJ has garnered in recent years. http://grants.intrasun.tcnj.edu/RecentlyFundedProposals.htm

-

-

“RT @NJAFLCIO: Proud to join in solidarity with faculty, staff, @AFTNJ and students at TCNJ to rally for a fair contract youtube.com/watch?v=kSAF1u…

-

“#council_contract Photos: TCNJ Day of Action for a fair contract and higher ed funding: bit.ly/Iy18jv #labor #union

-

“#council_contract College of New Jersey professors rally to protest contract dispute: By David Kar… bit.ly/JKfu63 #labor #union

-

“#council_contract Photos: William Paterson University Day of Action: bit.ly/KaIVNq #labor #union

-

“RT @SpencerKlein18: Proud to stand with NJ teachers at TCNJ! RT @AFTNJ: NJ United Students Spencer Klein shows student solidarity at TCNJ twitter.com/AFTNJ/status/1…

-

Union Calls For Fair Contracts For College Workers

STATE – Gov. Chris Christie’s promise to increase support for higher education should include fair contracts for workers, according t… -

College faculties protest lack of contracts

… 2012 in protest of what they say are delayed contract negotiations. Faculty have been working without a contract since June 30. ( TOM… -

Educators, professionals rally at NJCU, seeking new labor contract and tuition …

By Celeste Little/The Jersey Journal Several dozen educators and other professionals rallied yesterday at New Jersey City University, cal…

By Celeste Little/The Jersey Journal Several dozen educators and other professionals rallied yesterday at New Jersey City University, cal… -

Video: AFL-CIO joins TCNJ contract rally | American Federation of …

Video: AFL-CIO joins TCNJ contract rally. April 27, 2012 AFTNJ. Thousands of union members and student turned out fighting for a fair c… -

A spirited debate on NJ.com, with supporters and critics of the union protestors weighing in

-

Comments on College of New Jersey professors rally to protest …

2 days ago … To get a contract that’s fair for both sides of the negotiations, both …. I have tremendous respect for TCNJ and f…

2 days ago … To get a contract that’s fair for both sides of the negotiations, both …. I have tremendous respect for TCNJ and f… -

In the end, it’s the students who matter

Last week, our students presented their original research in our annual Celebration of Student Achievement. The research presentations ran the gamut, from a new software tool that will help journalists do a better job of extracting important information about the environment, to analyses of Medicare funding, to inventive applications of physical computing technologies and more. This is a TCNJ highlight reel from the 2009 Celebration that shows the kinds of things that can happen when faculty and students get to work closely together, appropriately supported by staff and with the right technology infrastructure. -

TCNJ Celebration for Student Achievement

There are others who can give you chapter and verse on the concessions that we’ve made over the years and the efforts that have gone into addressing shortfalls in funding for public higher education. We can also have a good discussion on the relative cost-benefit models for delivering higher-education through online or blended learning courses. College costs and accessibility are huge issues that need to be addressed in a mutually respectful and informed partnership. To participate in that partnership, taxpayers, bond investors and tuition payers have a right to know where their hard-earned college dollars are going. I hope this post helps provide a bit more of that needed transparency to help that process along. And with that, I must get back to grading. Thanks for your time.

Could journalists clear new Labor Department reporting roadblock by filing in html?

The Poynter Institute reports that the US Labor Department is imposing new rules on reporting on new employment data that could make it harder for reporters to file timely stories that are so critical to the financial markets. All credentialed news organizations will be forced to try to file their stories at the same time on department of labor computers only equipped with IE 9 and MS Word. In the past, the news organizations could bring their own equipment. The Labor Department says they are instituting the rules because in the past, some news organizations have violated their embargo – a requirement that the a news item be withheld until a certain time.

First, with everyone trying to file their stories at the same time, you know there will be more network congestion than you’d find in the arteries of a quintuple-bypass candidate. Second, some news orgs are complaining that the Word docs will require substantial reformatting to work with their content management systems. According to the Poynter story, the DOL officials were committed to implementing the new rules, despite the journalists’ expressed concerns.

Now I am wondering whether there would be an advantage for reporters who can insert the simple html formatting in the story and save the word document as plain text? If so, that’s another argument for why journalists need at least html and css. Nah, it can’t be that simple.

(h/t to M. Edward Borasky, whose Computational and Data Journalism curation site led me to the Poynter.org story.)

What the Trayvon Martin Tragedy Means for Us: April 18, 2012, 8-9 pm

Get the background on this event at the TCNJ African American Studies Department website. I am producing this chat in my capacity as department chair as part of the AFAM Salon series.

Bringing user experience design to journalism education

Jonathan Stray is a computer scientist and journalist who heads up a team at the Associated Press that creates interactive news stories. He has great ideas about how computer science can be used to make journalism more credible, sustainable and responsive to citizens’ needs.

He also asks really good questions that challenge treasured shibboleths in our profession. For example, Stray challenges the simplistic notion that our job is simply to deliver news. In the era before computational media, there was a logic to this – we reported; our readers, listeners and viewers decided. When done well and fairly, democracy was served. At least that was the hope, or as political science Jay Rosen might say, that’s our creed. But the computer scientist in Stray doesn’t abide such fluffy abstractions. In an excellent essay that is well worth considering in its entirety, he asserts,

Democracy is fine, but a real civic culture is far more participatory and empowering than elections. This requires not just information, but information tools.

What are information tools? What are they used for? By whom? How? How do we know when they work? These are the questions Stray tries to get us to think about by starting with the needs of our news users, instead of starting where we usually do, which is with the stories we are trying to report and disseminate. It’s hard to argue with him in principle, but what does it mean in practice? As he points out, it’s more than experimenting with story forms and distribution platforms.

To create tools, understand the customer

Stray’s line of reasoning took me back to lessons I learned from Bell Labs quality engineers in the 1980s about quality by design: quality is fitness for use by a customer. Product or service design requirements should flow from an understanding of customers’ needs. Customers are both internal (other members of an organization’s supply chain) and external (end users). Quality by design is a process of continual improvement, based on continual communications with internal and external stakeholders. Methodologies such as Total Quality Management and Quality Function Deployment were developed to operationalize those principles and generalize them as approaches to product and service development and marketing.

News Design=User Experience Design

Now comes the field of user experience design as a way of focusing an organization on ways of understanding and staying responsive to user needs. Most recently, I’ve been wrapping my mind around the literature on user experience design, especially, Whitney Quesenberry and Kevin Brook’s book, Storytelling for User Experience. Stray’s post is helping me think more concretely about how user experience design applies to journalism practice, and by extension, journalism education.

Smashing magazine has a concise introduction to user experience design that includes this definition of user experience:

User experience (abbreviated as UX) is how a person feels when interfacing with a system. The system could be a website, a web application or desktop software and, in modern contexts, is generally denoted by some form of human-computer interaction (HCI).

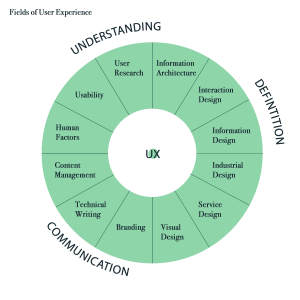

Fields of User Experience (from the blog A Nod to Nothing)

Fields of User Experience (from the blog A Nod to Nothing)For journalists, the challenge is to think about how our readers, viewers and users feel when interacting with our news products. According to our civic mission, we want them to feel invested in their communities, engaged in civic life, and empowered to act on the issues that matter to them.

Ethnography is one of the interesting techniques that the AP is using to understand user needs. In 2008, the Associated Press commissioned an ethnographic study of young news consumers. Nathanael Boehm neatly summarizes the role of ethnographic research in improving user experience:

Where usability is about how people directly interact with a technology in the more traditional sense, ethnography is about how people interact with each other. As UX designers, we’re primarily concerned with how we can use such research to solve a problem through the introduction or revision of technology.

What AP learned from its study of upscale “digital natives” in the US, UK and India is that the news consumers they’d most like to attract are often so overwhelmed by facts that they don’t seek the depth and context. Yet Stray notes that Wikipedia draws millions of users who invest significant time and energy on the site, suggesting that news organizations take a lesson.

From principle to practice

There is a great deal more that can be explored here, even as we think about journalism’s mission. For example, one of Stray’s pet projects is the development of an infographic tool that maps pundits’ sources of information. The ability to visually represent this kind of information can be helpful in assessing the credibility of claims. For my part, I’ve been thinking about tools that make complex data more intelligible to the people who need it. For example, this semester, my students and I are thinking about social media tools that will make it easier to make sense of environmental data that affects their lives. We want to improve the accessibility of such tools as the Environmental Protection Agency’s EJView and the state of New Jersey Department of Environmental Protechon’s Data Miner sites. More about this work in a future post.

- «Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- …

- 40

- Next Page»