Whose Facts Matter?

A Cautionary Tale

Part Three: When "Objectivity" isn't objective

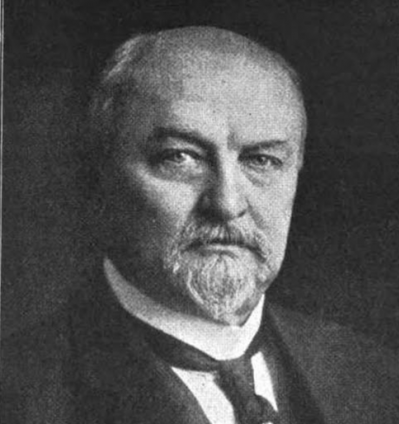

In part one of this text, we saw the difficulty that scholar W.E.B. Du Bois had dissuading muckraking journalist Ray Stannard Baker from repeating racist stereotypes in a series of in-depth articles about race in America in the early 20th century.

Du Bois, who directed extensive research studies on black life, argued that Baker exaggerated the problem of African American crime, and gave too little attention to voting rights.

DuBois and others helped Baker collect dozens of interviews, photos and statistics from the south, northeast and midwestern US.For example, this photo shows a black worker's family in their Atlanta, Georgia home.

The amount of income cleared by the states on convict labor is something enormous.

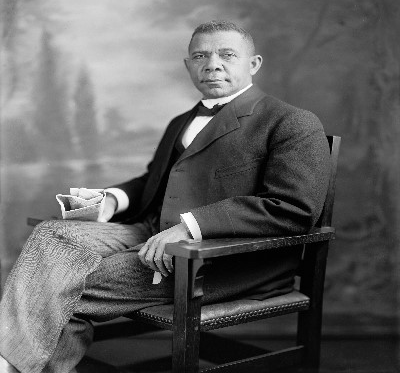

Baker did heed some suggestions from Du Bois and Booker T. Washington, founder of Hampton University. Washington, for example, urged him to investigate convict leasing in the South. Bakerreported that the demand for cheap prison labor, "explains in some degree, the very large number of criminals, especially Negroes, in Georgia."

The poorer class of Negroes [is] naturally indolent..."

";

Evidence such as these images of industrious and educated Black men contradicted his claims, but Baker insisted, "Every investigator necessarily has his personal equation or point of view. The best he can do is to set down the truth as he sees it, without bating a jot or adding a tittle, and this I have done."p. viii

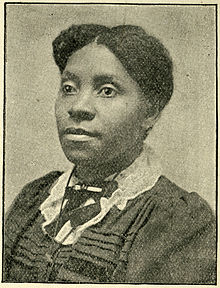

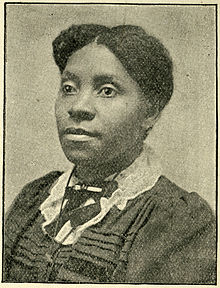

Wells documented the horrors of lynch law.In demand as a writer and speaker in the US and in England, the New York Times called her a "nasty-minded mulatress." In a 2017 interview, Mindich said, "It's almost as if white reporters couldn't fathom that African Americans were being terrorized by whites in the South."

Indeed, historian Khalil Muhammad argues that leading scholars such as Nathaniel Shaler used statistics to advance pseudo-scientific ideas about black inferiority. DuBois, who had studied with Shaler, produced evidence of black resilience and progress in the face of hostile structural forces. That evidence did not shift the mainstream scholarly or public policy discourse. By contrast, the problems of European immigrants were seen as having structural roots that could be addressed through policy reforms.

[Newspapers preferred European immigrants to the] "lazy, improvident, child-like, irresponsible, chicken-stealing, crap-shooting, policy-playing, razor-toting, immoral and criminal" Negro.

Historian Rayford Logan found that racism permeated mainstream American newspaper and magazine coverage of racial issues during the post-reconstruction era.(Logan)

Mindich argues that mainstream journalists at the turn of the 20th century promulgated the notion that only college-educated white males who adopted a dispassionate reporting style were capable of being truly objective.

Wells was thwarted in her attempts to be heard because the idea that whites were more civilized than blacks was deeply ingrained in white journalists' belief systems... The second barrier against Wells was that she belonged in the three categories that elites used to define "non-objectivity:" she was an outsider, a woman and a member of an "uncivilized race."

David Mindich

Baker covered lynching in the North and South, and relied on newspaper reports and a range of white informants.He acknowledged that many lynchings were not related to rape. But like the Times, he is sympathetic to claims about black criminality. He concludes:

Lynching in this country is peculiarly the white man's burden. The white man has taken all the responsibility of government; he really governs in the North as well as in the South, in the North disfranchising the Negro with cash, in the South by law or by intimidation. All the machinery of justice is in his hands. How keen is the need, then, of calmness and strict justice in dealing with the Negro! Nothing more surely tends to bring the white man down to the lowest level of the criminal Negro than yielding to those blind instincts of savagery which find expression in the mob.

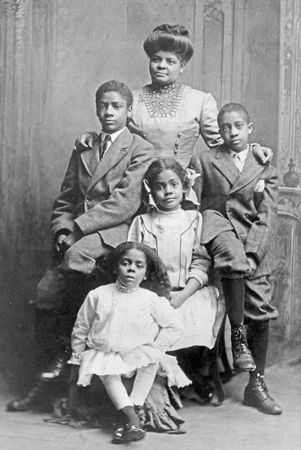

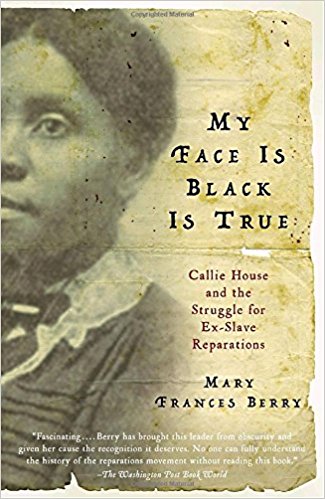

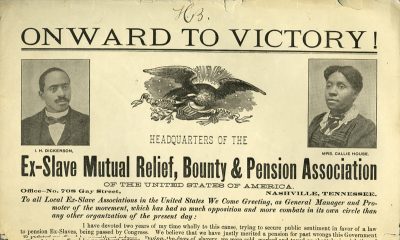

By 1906, House and her allies had built a grass-roots organization with thousands of dues-paying members. The funds paid for a mutual aid organization and for lobbying efforts for a law granting pensions for ex-slaves. House also battled government harassment that would result in her 1916 trial and imprisonment on fraud charges that were later proved spurious. (Berry)

The most learned Negroes have less interest in their race than any other Negro as many of them are fighting against the welfare of their race.

Baker relied on "learned Negroes" such as DuBois and Booker T. Washington for the names of people to interview. House's agenda lacked support from black leaders, politicians and journalists.DuBois and Washington ignored the movement and African American members of Congress opposed it.They preferred other strategies, such as expanding education opportunities.

Part of what makes Baker's work intriguing is that we can see evidence of his pursuit of objectivity as Mindich defines it. In pursuit of facts, Baker cites statistics on both positive and negative aspects of black life: business and property ownership, education, alongside crime data. He acknowledges that statistics belie assertions of rampant criminality in predominantly-black areas in the South. He cites racial discrimination in the courts and the profitable practice of convict leasing as factors in the disproportionate imprisonment of black men. In pursuit of balance, detachment and non-partisanship, his sources range from the white supremacist editor and politician James Vardaman to the militant civil rights journalist Monroe Trotter. He circulated his drafts for feedback. Unlike the journalists cited by Muhammad and Logan, he doesn't make invidious distinctions between African Americans, immigrants and the US-born white working class. He anticipates today's solutions journalists by highlighting black self-help and potential areas of interracial cooperation.

At the same time, his reporting was constrained by several factors. First, his view of Civil War history comported with the dominant view that Reconstruction failed because African Americans weren't ready for full citizenship. This scholarship wouldn't be challenged for another 30 years, when DuBois' Black Reconstruction was published. Here, historian Eric Foner debunks this misconception.

Another commonly-held belief that has been debunked by more recent scholarship is the idea that newly-emancipated people had no skills beyond what whites taught them. Anthropologist Sheila Walker is one of the scholars who have identified skills and knowledge that Africans brought to the United States that has continued to influence both American and African American cultures. She offers examples in this interview with Rock Newman, beginning at 45:00. "We were brought not just for our bodies, but our minds," Walker says.

More examples here andA final limitation of Baker's reporting is his version of false balance. As explained in Part 1, Du Bois took Baker to task for granting so much space to assertions that white people were leaving the rural South over fears of black crime. He pointed out that statistics didn't support those assertions, and white migrants had other motives for moving, such as seeking better schools and jobs. Like the editors of the New York Times in their response to Ida B. Wells, Baker engaged in false balance. As this YouTube clip demonstrates, this is still a problem.

|

Click for audio

Since the release of the 1968 Kerner Commission report, of course, there has been considerable attention to making newsroom staffs and methods more representative and diverse.

Well, I think that there is just too much indifference to the whole idea of diversity... I mean, the number of newsrooms in this country that have no people of color at all in them is appalling.

In a 2015 PBS Newshour interview,, media columnist Richard Prince lamented the toll that a negative business climate has taken on the industry's commitment to newsroom diversity.

Michelle Duster, the great-grandaughter of Ida B. Wells, sees disturbing parallels between Wells' era and the dangers African Americans today.

Black men are still being used as scapegoats for crimes they didn't commit. I remember the almost mob-like frenzy to get the Black men who beat and raped the white, female Central Park jogger in 1989. Five Black teenage males were arrested and convicted of the crime. They served 7-11 years for a crime they didn't commit. In 2002, those five men were released after the one man who actually committed the crime was convicted.

Michelle Duster

Natalie Byfield reported the Central Park Jogger story, then studied the press coverage for her book, Savage Portrayals:"This case became an extreme example of how new narratives about racial groups based on the notion of color-blind racism make it possible for the use of racist tropes from the past and the existence of unequal racial outcomes to be dismissed by mainstream institutions as having little or no relationship to the country's historical and material foundations of racial inequality."

|

Byfield employs ethnography, memoir and content analysis to explain how the organizational culture and reporting routines at the New York Daily News, where she worked at the time of the Central Park Jogger case made it more likely that stories would emerge that comported with negative race, class and gender stereotypes.

In part three, we will examine one newsroom's effort to use computational journalism to bring greater efficiency, depth and context to its reporting. The results, as we shall see, were mixed.

via GIPHY>

Endnotes

- Some examples of Baker's paternalism:

- Page 99

Most Negroes, as I have said, were (and still are, of course) farm-dwellers, and farm-dwellers in the hitherto wasteful Southern way. Their living is easy to get and very simple. In that warm climate they need few clothes; a shack for a home. Their living standards are low; they have not learned to save; there has not been time since slavery for them to attain the sense of responsibility which would encourage them to get ahead. And moreover they have been and are to-day largely under the discipline of white land owners. What was the effect, then, of a rapid advance in wages? The poorer class of Negroes, naturally indolent and happy-go-lucky, found that they could make as much money in two or three days as they had formerly earned in a whole week. It was enough to live on as well as they had ever lived: why, then, work more than two days a week? It was the logic of a child, but it was the logic used. Everywhere I went in the South I heard the same story: high wages coupled with the difficulty of getting anything like continuous work from this class of coloured men.

- Page 215

Lynching in this country is peculiarly the white man's burden. The white man has taken all the responsibility of government; he really governs in the North as well as in the South, in the North disfranchising the Negro with cash, in the South by law or by intimidation. All the machinery of justice is in his hands. How keen is the need, then, of calmness and strict justice in dealing with the Negro! Nothing more surely tends to bring the white man down to the lowest level of the criminal Negro than yielding to those blind instincts of savagery which find expression in the mob. The man who joins a mob, by his very acts, puts himself on a level with the Negro criminal: both have given way wholly to brute passion. For, if civilisation means anything, it means self-restraint; casting away self-restraint the white man becomes as savage as the criminal Negro. If the white man sets an example of non-obedience to law, of non-enforcement of law, and of unequal justice, what can be expected of the Negro? A criminal father is a poor preacher of homilies to a wayward son. The Negro sees a man, white or black, commit murder and go free, over and over again in all these lynching counties. Why should he fear to murder? Every passion of the white man is reflected and emphasised in the criminal Negro.

- Page 303

Thousands of Negroes in this country are fully as well equipped, fully as patriotic, as the average white citizen. Moreover, they are as much concerned in the real welfare of the country. The principle that our forefathers fought for, taxation only with representation, is as true to-day as it ever was. On the other hand, the vast majority of Negroes (and many foreigners and poor whites) are still densely ignorant, and[Pg 303] have little or no appreciation of the duties of citizenship. It seems right that they should be required to wait before being allowed to vote until they are prepared. A wise parent hedges his son about with restrictions; he does not authorise his signature at the bank or allow him to run a locomotive; and until he is twenty-one years old he is disfranchised and has no part in the government. But the parent restricts his son because it seems the wisest course for him, for the family, and for the state that he should grow to manhood before he is burdened with grave responsibilities. So the state limits suffrage; and rightly limits it, so long as it accompanies that limitation with a determined policy of education. But the suffrage law is so executed in the South to-day as to keep many capable Negroes from the exercise of their rights, to prevent recognition of honest merit, and it is executed unjustly as between white men and coloured. It is no condonement of the Southern position to say that the North also disfranchises a large part of the Negro vote by bribery, which it does; it is only saying that the North is also wrong. As for the agitation for the repeal of the Fifteenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution, which gives the right of suffrage to the coloured man, it must be met by every lover of justice and democracy with a face of adamant. If there were only one Negro in the country capable of citizenship, the way for him must, at least, be kept open. No doubt full suffrage was given to the mass of Negroes before they were prepared for it, while yet they were slaves in everything except bodily shackles, and the result during the Reconstruction period was disastrous. But the principle of a free franchise fortunately, as I believe, for this country has been forever established. If the white man is not willing to meet the Negro in any contest whatsoever without plugging the dice, then he is not the superior but the inferior of the Negro.

- Sentimentalizing slavery

- Page 88

The good landlord, generally speaking, is the one who knows by inheritance how a feudal system should be operated. In other words, he is the old slave-owner or his descendant, who not only feels the ancient responsibility of slavery times, but believes that the good treatment of tenants, as a policy, will produce better results than harshness and force.

- Franklin, VP. W.E.B. Du Bois as Journalist, Journal of Negro Education, Vol. 56, No. 2 (1987). P. 240-244