Monday, August 28, 1963 marks the 60th anniversary of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the occasion most remembered for the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr’s “I Have a Dream” oration. Over the weekend, thousands of people returned to the Lincoln Memorial for what organizers described as a “Not a commemoration – a continuation” of the Freedom Movement. (I am using “Freedom Movement” to what is generally known as the Civil Rights Movement after conversations with Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee veteran Ruby Sales. Sales notes that this is the way the activists referred to their work, seeing it as part of a long tradition of advocacy and resistance stretching backwards and forwards across time and distance.)

Current events have a cruel way of underscoring the need to stay in the fight against hatred and oppression. As the thousands gathered in Washington, police say a 21-year-old White man who hated Black people walked into a Dollar General store in Jacksonville, Florida, shot three Black strangers to death, then turned the gun on himself. The next day, mourners gathered at Jacksonville’s St. Paul’s AME Church. According to a report in The Guardian, Rev. Willie Barnes exhorted congregants to hold on to Jesus’ hands but confessed, “I’m fighting, trying not to be angry.” Jacksonville Mayor Donna Deegan wept, saying, “It feels some days like we’re going backward.”

In about one month, the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH) plans to hold its 108th Annual Conference in Jacksonville. For several months, ASALH leaders have criticized Florida’s political leaders for the restrictions they have imposed on the teaching American history in its public schools. Most recently, Dr. Johnetta Betsch Cole, president emerita of Spelman College and Bennett College, decried the Florida Board of Education’s imposition of new middle school standards demanding that children be taught “how slaves developed skills which in some instances could be applied for their personal benefit.” Noting the decades of scholarship documenting that enslaved Africans came to these shores with a wealth of skills and knowledge, Cole concludes,

Throughout my life that began in Jacksonville, Florida during the days of legal segregation, I have built positive relationships with White people who unequivocally admit to the injustice of enslavement. I am left wondering who Florida’s new academic standards are meant to serve, because they clearly do not serve Black children, White children or any other children who are capable of far more honesty and courage than Florida’s school system seems to be willing to admit. We must do all that we can to stop the Florida Board of Education from requiring middle schools to teach these new so called academic standards that perpetuate ignorant and bigoted ideas about enslaved Africans who with their descendants have helped to build our country and are committed to continuing the struggle toward a more perfect union.”

Johnetta Betsch Cole, Ph.D. “Florida’s New Middle School Standards Will Harm All of Florida’s Children”

Reflecting this weekend on the anniversary, the news, and the work ahead, I found valuable insight in several episodes of Prof. Meacham’s “It Was Said” podcast. The podcast places great speeches from the 20th century in the context of their historical moment, and two excellent episodes give particular attention to the March. One, future Congressman John Lewis‘ “We Want Our Freedom Now,” illuminates how the young president of SNCC navigated the pressure from the older March leaders and even the White House to tone down criticism of the Kennedy administration and demands for immediate action in his draft. You can watch the speech below and hear the podcast episode here.

Lewis began, “We march today for jobs and freedom, but we have nothing to be proud of…,”

The other episode, MLK Jr., The Last Speech, is actually focused on Dr. King’s April 3, 1968 “Mountaintop” speech, delivered the day before his assassination, but it includes the “I Have a Dream” speech as well, focusing on its little-discussed argument for economic justice – an argument that he would repeat and refine until the end of his life.

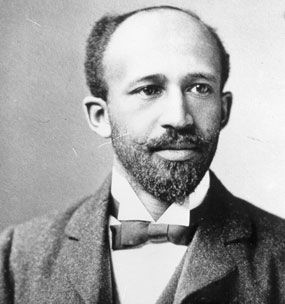

It was also at the 1963 March that Roy Wilkins, Secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, announced the death of the protean scholar and activist William Edward Burghardt DuBois, a cofounder of the organization Wilkins led. Not long before, from his home in Accra, Ghana, Du Bois had been one of the many senders of congratulatory telegrams to the march organizers.According to a published excerpt from Charles Euchner’s book, Nobody Turn Me Around: A People’s History of the March on Washington (Penguin/RandomHouse, 2011), Du Bois wrote, “One thing alone I charge you, as you live, believe in Life! Always human beings will live and progress to greater, broader and fuller life. The only possible death is to lose belief in this truth simply because the Great End comes slowly, because time is long.” Nonetheless, Wilkins’ tribute had been begrudging. He had been sharply critical of Du Bois’ turn toward Marxism, initially saying, “I’m not going to announce that Communist’s death.” Fellow March leaders Bayard Rustin and Asa Phillip Randolph changed his mind, and Wilkins said,

“Regardless of the fact that in his later years Dr. Du Bois chose another path, it is incontrovertible that at the dawn of the twentieth century his was the voice that was calling to you to gather here today in this cause. If you want to read something that applies to 1963 go back and get a volume of The Souls of Black Folk by Du Bois, published in 1903.”

Roy Wilkins cf Charles Euchner Nobody Turn Me Around

In a 1961 oral history recorded with Smithsonian Folkways, Du Bois recalled his turn from pure scholarship to activism. You can hear him tell his story in his own voice:

As Euchner and others have documented, Wilkins want Bayard Rustin to have a leadership role in the March because he was gay. He wasn’t alone in his antipathy. I couldn’t help but think of him when I opened my podcast feed this morning and found the final installments of the searing and thoughtful limited-edition podcast series After Broad and Market, helmed by veteran journalist Jenna Flanagan. (As of this writing, the website doesn’t have the most recent episodes posted, but they can be heard if you click on any of the podcast hosting links, and I imagine the website will be updated soon.) In June, Flanagan made a TikTok video introducing the series and explaining what the series was about and why it mattered so much to her.

@jflannys Say her name! Sakia Gunn! Sakia Gunn! Sakia Gunn! I have been waiting 20-years to unpack and retell this story. I was shook when I learned of the murder of 15-year old Sakia Gunn for being an out and proud lesbian in Newark, NJ. But I was more shook by the lack of attention and interest her story garnered. Black girls have the right to live openly, move freely and love unapologetically and my new Podcast, After Broad and Market explores why we still struggle to let that happen AND how Newarks Queer community is working tirelessly to keep Sakia’s name alive. Follow anywhere you get podcasts! #sakiagunn #pride #sayhername ♬ original sound – Jenna Flanagan

I have personal and professional connections to each of these stories – I’ve written in the past about how my parents, aunt and uncle attended the 1963 March on Washington (I was in the city but considered to young to March, so I saw it on TV.) I serve on the editorial board of ASALH’s Black History Bulletin. And when Sakia Gunn was murdered, I felt led to track the press coverage for the next two years on my blog, up to the time of the conviction and sentencing of her killer. Having learned about the murder from an email from a former student who had spent part of her adolescence hanging out at the Chelsea Piers and coming back to her Newark-area home in the wee hours, I had a visceral reaction as a woman, a mother, and educator that led me to write a poem, A Libation for Sakia.

Both the media monitoring work and the poem got some attention from activists, scholars and journalists at the time, and like Flanagan, Sakia’s story never left me, even as I went on to study, write and teach about other issues. So I suppose that I shouldn’t have been surprised when Flanagan and her colleagues contacted me for an interview about the work I did back then, but I was. You hear my voice in the first episode of the series, and in a bonus episode in which I read the poem. But that’s not the reason to listen to the series.

Listen to the series because Flanagan does a beautiful job of letting the people who were close to Sakia Gunn tell her story, and their own. She also gives center stage to the activists and community leaders who have been working to make Newark safer over the last 20 years. Listen, too, as she reflects on how Sakia’s story challenged her as a Black woman journalist, and it affected the thinking of scholars and artists. And listen as she connects the dots between what happened to Sakia and the depressingly similar murder of Philadelphia-born dancer O’Shea Sibley at a gas station in New York City earlier this summer.

In a June, 2023 interview about the podcast series, Flanagan told WNYC’s Brian Lehrer, “As a young Black woman, [Sakia’s story] was one of those reminders that no, people don’t value your life in the same way. I think that’s part of the reason why the story just never left me.” Yeah, that part.

Bayard Rustin said, “When an individual is protesting society’s refusal to acknowledge his dignity as a human being, his very act of protest confers dignity on him.” By that definition, Sakia Gunn died with dignity, but she shouldn’t have had to. Ella Baker, the executive director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and guiding spirit behind the creation of SNCC, said, “We who believe in freedom cannot rest,” and SNCC Freedom Singer Berniece Johnson Reagon put that in a song. This is the charge to us today.

I am on an Amtrak train barreling south toward Raleigh, North Carolina for the 95th annual convention of the

I am on an Amtrak train barreling south toward Raleigh, North Carolina for the 95th annual convention of the