Note: This is a re-creation of a post that was originally published on BlogHer.com in 2010. Since BlogHer was sold to SheKnows.com, some content has become inaccessible.

Dear Great Grandfather Jordan,

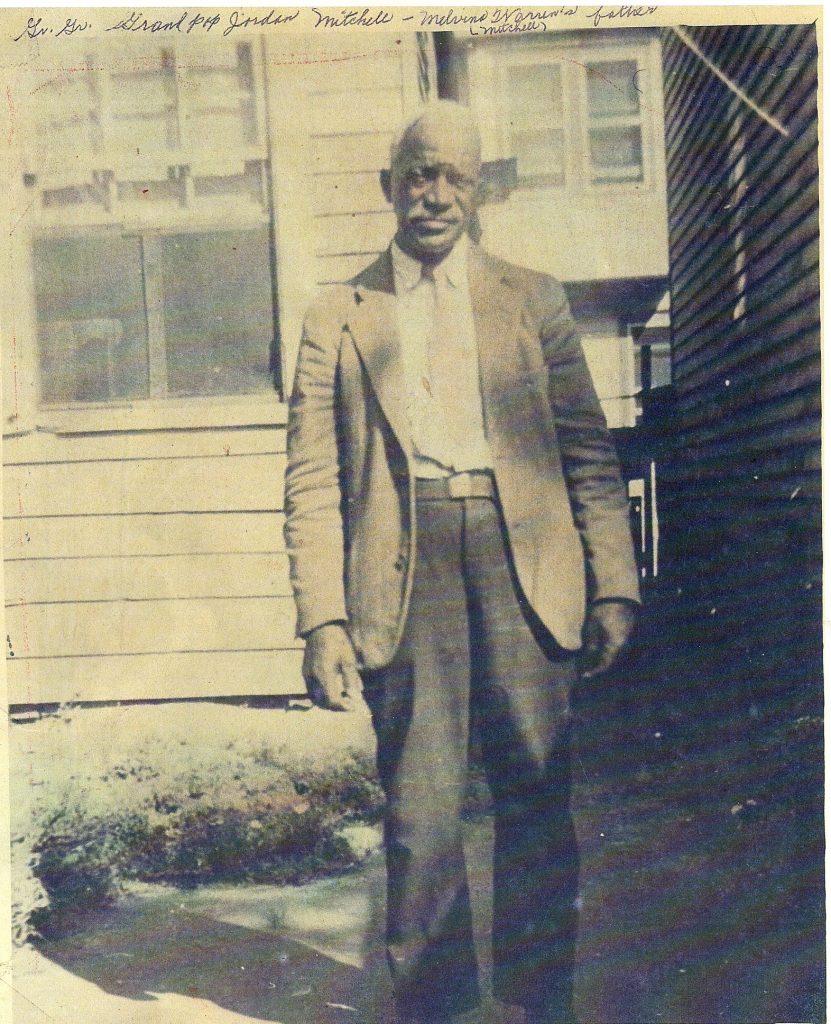

I write to you with some trepidation, not knowing what, if any, characteristics or values accompany a soul as it traverses from the mortal to the immortal plane. You lived from the mid-19th century to the mid-20th, and like most men of that time, I’m told that you held to the belief that children were to be seen and not heard. Uncle Bill told me that among your daughter Mattie’s children, you shared your slavery-time stories almost exclusively with him, since he was the oldest living, and a boy besides. Then again, cousin Mel heard a tale or two from you, perhaps from when you stayed at Melvina’s house (his grandmother, your daughter). But you have haunted me since I learned about you back in 1977, and now I have a picture of you, and there are things I must know.

I first learned of you while watching “Roots”, the landmark miniseries about one family’s journey from Africa, through the Middle Passage, to slavery and the epic struggle for freedom. I think it was during the scene where Kunta Kinte’s foot gets chopped off for running away that my Dad quietly said, “My grandfather used to talk about that.” I stared at my father. Your grandfather? “Yes, he was a slave.” You KNEW him? Yes, he lived with us. WHAT?

I peppered him with questions and soon learned that you were born in Devereux, Georgia, in Hancock County, about 100 years before me, and you almost lived long enough to be there for my birth. You and your family were owned by John Mitchell. Your wife, Martha Holsey Mitchell, had also been a slave. She died when my father was a toddler. You were strong and able for most of your life until someone decided that you should see Georgia again before you died, and after that, you were all mixed up about past and present, places and people.

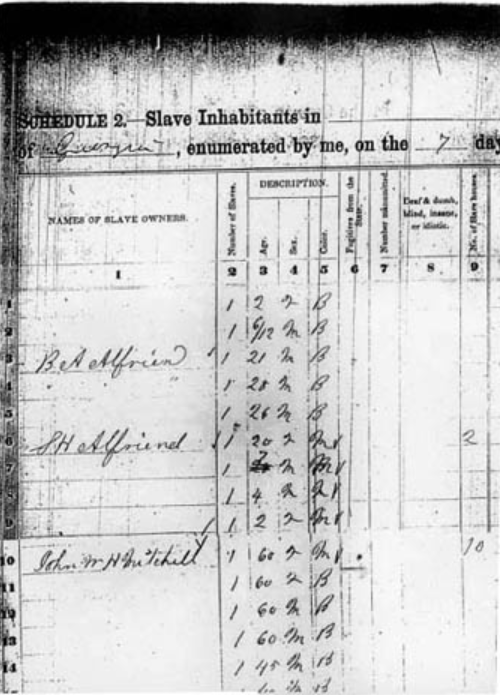

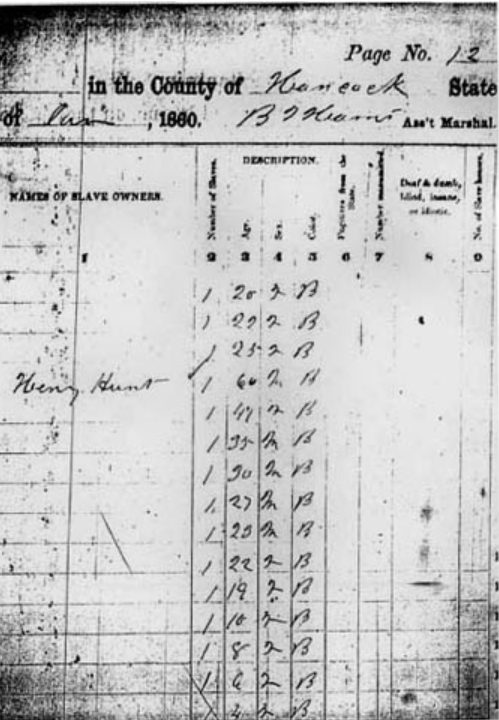

Returning to campus that Sunday, I went straight to the microfilm room in Firestone Library at Princeton and pulled the reels for the 1860 Census. The were the free rolls and the slave rolls, organized by county. From the free rolls, I found two John Mitchells. One had six slaves, but John WH Mitchell, owned 34. This was probably the man, I reasoned, since my father had referred to a plantation. The man who owned my family.

That took me to the slave rolls, where I learned that you and your family weren’t recorded as people, but catalogued like livestock. In the left column was the owners name, and each slave was listed individually according to characteristics related to property value: male or female, black or mulatto, approximate age, and special notations for runaways, those who had been manumitted, and those who were “Deaf, blind, insane or idiotic.” Here is the beginning and end of the inventory under John WH’s name:

I stared at that microfilm for what seemed like a long time, my eyes flooding with water. It was real. You were real. You were a little boy. Somewhere in there, there were brothers sisters, parents. It happened. It happened to my own flesh and blood. And no one thought you were important enough to record your name. I had to use family lore to find you. And here I was at Princeton, being trained to trust official sources and records. I staggered from the microfilm room with the printout in my hand, showing it to anyone I knew. I never felt the loss of Grandmom Mattie more keenly than at that moment. She had died just before Thanksgiving, freshman year. I needed to talk to her; I needed to see you.

I stared at that microfilm for what seemed like a long time, my eyes flooding with water. It was real. You were real. You were a little boy. Somewhere in there, there were brothers sisters, parents. It happened. It happened to my own flesh and blood. And no one thought you were important enough to record your name. I had to use family lore to find you. And here I was at Princeton, being trained to trust official sources and records. I staggered from the microfilm room with the printout in my hand, showing it to anyone I knew. I never felt the loss of Grandmom Mattie more keenly than at that moment. She had died just before Thanksgiving, freshman year. I needed to talk to her; I needed to see you.

A few years later, with the help of a photographer friend, I got some additional details about your life from Cousin Claudia. Her grandmother was your sister, whom they called Aunt Duck. You were close in age. Aunt Duck said you all had to get your food from a big trough, like what they use to feed horses. She also remembered beatings, but there were some times of singing and dancing as well, especially the shouts of “We are free!” when news came that slavery had ended.

Of course, I wondered what the war had been like for you and yours. My son, your great-great grandson, wondered, too — so much so that during his middle-school years, he played the role of fifer in the U.S. Colored Troops — more than 209,000 black people fought in the Union blue to win their freedom. You were too young, of course, and they were coming from the North, but I wonder whether you saw them, or whether your older brothers, Holland, Ned, or Henry, for example, had any thoughts of joining up.

I wonder what your parents, Holland and Judy Priscilla, thought, too. Cousin Mel said your father was seven feet tall and so strong that the master put him in charge of the other slaves. He said you told a story about how your Daddy let the master beat him with the lash one time just to show “how things were going to go,” as he put it. I wonder whether it was your boyhood reverence of your old man that made you think that he was in a position to dictate how many lashes the master could give a slave.

You lived most of your life as a free man, under the cruel vagaries of de jure segregation in the South and de facto segregation in the North. You would have been the same age as the exploited tenant farmers and laborers that WEB Du Bois described in this chapter from The Souls of Black Folk about his sojourn through Dougherty County Georgia:

It is a land of rapid contrasts and of curiously mingled hope and pain. Here sits a pretty blue-eyed quadroon hiding her bare feet; she was married only last week, and yonder in the field is her dark young husband, hoeing to support her, at thirty cents a day without board. Across the way is Gatesby, brown and tall, lord of two thousand acres shrewdly won and held. There is a store conducted by his black son, a blacksmith shop, and a ginnery. Five miles below here is a town owned and controlled by one white New Englander. He owns almost a Rhode Island county, with thousands of acres and hundreds of black laborers. Their cabins look better than most, and the farm, with machinery and fertilizers, is much more business-like than any in the county, although the manager drives hard bargains in wages. When now we turn and look five miles above, there on the edge of town are five houses of prostitutes,—two of blacks and three of whites; and in one of the houses of the whites a worthless black boy was harbored too openly two years ago; so he was hanged for rape. And here, too, is the high whitewashed fence of the “stockade,” as the county prison is called; the white folks say it is ever full of black criminals,—the black folks say that only colored boys are sent to jail, and they not because they are guilty, but because the State needs criminals to eke out its income by their forced labor.

Was this the land you knew and the life you lived? Did you know about the debates between Du Bois and Booker T over whether and when you needed higher education, or the vote, or an end to lynch law — and how to achieve it? Had your father told you of Frederick Douglass, who had pondered the Meaning of the Fourth of July to the Negro back in 1852 — indeed, did he know?

The censuses of 1910 and 1920 record your name like any other householder, along with your wife Martha and children. You were sharecropping on the Mitchell plantation, and worshipping at Mitchell chapel, one of the five small churches built on the old place. I heard tell that they built the churches near the trees where they use to have camp meetings during slavery time — sure would like to ask you about that. They all bear family names — Mitchell Chapel, Warren Chapel. Pearson Chapel 1s now an AME Church. Must be a fine place with its own road named after it … Cousin Nonie used to talk about going there in the buggy, when they could borrow the mule. I also heard about how easy it was to lose your land to the taxman or your life to the lynch mob. Then there was the boll weevil, and the tales of better times up North. What exactly it was that drew you above the Mason Dixon, I can’t pretend to know.

By the 1930s you had come to New Jersey. Mel says that picture was taken in Burlington, although he doesn’t know the exact circumstance — “It was just always around.” Great-grandmom Martha — described as a small, quiet woman — went to be with the Lord in 1936, but you lived about another 15 years. They say you kept to a lot of your country ways, walking everywhere, so far and fast that half the time your family didn’t know where you were.

You lived long enough to see Claudia, your baby sister’s granddaughter, graduate from college and become a teacher — so many of us have followed her lead that some of us joke that it’s the family business. I wonder what you thought. I hope you were proud.

Maybe I’ll never know in words what you thought about all of these things, but I know that you endured and brought your family through. And in the end, I guess that’s all that matters. Thank you, Great-Grandpa. Happy Independence Day.

Related:

- My 2004 review/memoir of Edward Jones’ The Known World

- Tonya Bolden’s Tell All the Children Our Story is a great introduction to the history of African American children

- AfriGeneas is a great starting point for exploring your African American roots