Author’s note: This part of my unpublished 2002 essay, “Not the Subject but the Premise: Postcards from the Edge of Du Bois’ Black Belt,” is being reproduced here for comment and as fodder in the body of work upon which I am drawing for my sabbatical project. I consider it to be a failed work with some useful nuggets.

Of the Dawn of “Objective” Journalism

Du Bois wrote Souls at time when both journalism and the social sciences were becoming defined as professions. David Mindich has shown persuasively that the objective journalism model — the “just the facts” approach to news — emerged gradually between 1830 and 1896. Mindich identified five key elements of the traditional definition of objective journalism:

Du Bois wrote Souls at time when both journalism and the social sciences were becoming defined as professions. David Mindich has shown persuasively that the objective journalism model — the “just the facts” approach to news — emerged gradually between 1830 and 1896. Mindich identified five key elements of the traditional definition of objective journalism:

• Detachment

• Non-partisanship

• Facticity

• Inverted pyramid story structure (relating the key facts first, then adding details in succeeding order of importance),

• Balance (presenting two sides of a story — which usually means presenting quotes from opposing experts.) (Mindich)

Before the rise of the objective journalism model, a newspaper or journal of opinion was likely to be a jumble of factual accounts, fiction, gossip and polemic. Most journalists were freelance “correspondents;” 19th century media owners were sole proprietors who sometimes also served as postmasters and owned printing businesses. Many newspapers and magazines were explicitly linked to political parties or causes; this became less true as the century wore on.

By the end of the 19th century, American journalists had become scouts and ambassadors for a country that was just ascending to imperial power. William Mc Kinley declared that God had told him to wage bloody guerilla war in the Philippines, Commodore Perry demanded that Japan open her borders to American industry, and Yankee grit and ingenuity had split the hemisphere at the Isthmus of Panama. At Worlds’ Fairs and exhibitions from Chicago to Buffalo to Paris, Americans portrayed themselves as the avatars of civilization. American newspapers and magazines celebrated and debated the perquisites and perils of empire. The media of that day helped white Americans, particularly, forge a new consensus about their new place in the world. Others – Native Americans, along with some European, Asian and Latin American immigrants, and especially people of African descent, found themselves placed on progressively lower rungs on the continuum between civilization and barbarity.

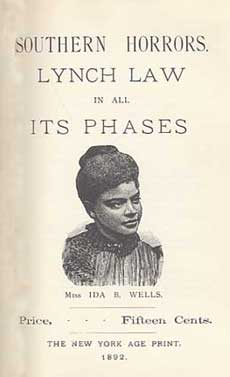

For black journalists in a culture in which scientific racism was normative, adherence to the tenets of objective journalism was logically and existentially absurd. Then, too, so was daring to tell the truth. Du Bois’ contemporaries, Ida Wells Barnett, Pauline Hopkins, Monroe Trotter and others, would endure death threats, ostracism and other forms of condemnation for reporting on and crusading against lynching and other outrages.

In fact the New York Times, then as now considered the apotheosis of objective journalism, specifically savaged Wells as, “a nasty-minded mulatress, who does not scruple to represent the victims of black brutes in the south as willing victims.” (Mindich, p. 128) Wells’ sin was that she dared to independently investigate official accounts of lynchings, and frequently found them to be false. The Times’ typical lynching story, written in third-person, inverted pyramid style, presented the summary mob execution of black men as a given communities’ understandable reaction to black rapists that preyed on innocent white women and girls. Wells reported that in many instances, the black men were involved in consensual relationships with their purported victims. Sometimes they were even married. In other instances, the precipitating incident had been falsely reported as rape, when in it was actually, for example, a dispute of over unpaid wages.

The errors in the Times‘ accounts were generally based on flawed, racist premises: that southern sheriffs or correspondents were reliable of disinterested sources and that academic, religious and political “experts” were reliable informants about the South and the Negro. Wells’ reporting was dangerous both because it exposed those flawed premises, and because, in the worldview from which they emerged and that the Times helped sustain, her black female mind and body were not supposed to be capable of amassing and presenting such a powerful indictment. (Mindich, p. 128-30.)

Du Bois compiled the essays in Souls of Black Folk at a time when he realized that empirical evidence of black humanity would neither end racism nor result in reasoned public policy. He had provided such evidence in the The Philadelphia Negro; Wells had done it in The Red Record; many others had done it as well. Neither sociological analysis nor factual reporting had quelled the lynch mobs or prevented blacks from being thrown out their elected offices, turned away at the polls, and dispossessed from whatever land or goods they had managed to acquire. Especially, scholarship and probity had not protected his only son, Burghardt from the deadly effects of wretched Jim Crow living conditions.

Du Bois reached, therefore, for a journalistic form that was authoritative, empirical, but also rhetorically effective. As he explained in his 1944 essay, “My Evolving Program for Negro Freedom:” his writing during this period, “was directed at the majority of white Americans, and rested on the assumption that once they realized the scientifically attested truth concerning Negroes and race relations, they would take action to correct all wrong.” By the turn of the century, his platform had expanded to encourage, “united action on the part of thinking Americans, black and white, to force the truth concerning Negroes on the attention of the nation.” (Lewis, Reader, p. 617-18)

truth concerning Negroes on the attention of the nation.” (Lewis, Reader, p. 617-18)

Still, Du Bois’s journalism fit Mindich’s definition of objectivity in several important respects. It was detached, in that his work was not explicitly tied to a particular political faction or party. It was non-partisan, particularly, in its effort to walk a line between Booker T. Washington’s conservatism and such radicals as his Harvard friend, Monroe Trotter, publisher of the flame-throwing Guardian. Although he attributed sources in a way that would not be acceptable today, there is no question that he strove for factual reporting. With a style more suited to interpretive news features than hard news, he was unlikely to use the inverted pyramid. Finally, while he never pretended to be neutral on the matters of race and equality, he did present contrary interpretations of his evidence – interpretations that he proceeded to meticulously refute.