The Criteria for Negro Art in the Age of Computational Media

In June, 2008, I attended a presentation in which Henry Jenkins, then Director of the Comparative Media Studies program at MIT, contemplated the lessons of Soulja Boy Tellem’s use of what he calls “participatory culture” to create a career as a hip-hop star. Jenkins described how teenager DeAndre Ramone Way (Soulja Boy) built a fan base by posting the music and a home video of his song, “Crank Dat,” and encouraging listeners to remix it, make video responses to it, and share it freely. (The presentation video is only available to members of the New Media Consortium.)

The process illustrates Jenkins’ concept of “spreadable” culture — a term that he argues is more accurate than the “viral” model, since viruses proliferate by attacking their hosts, while “spreadable” culture invites voluntary participation. He showed examples of fan videos of “Crank Dat,” including produced by his MIT grad students. Then Jenkins paralleled Soulja Boy’s encouragement of artistic appropriation and the cultural borrowing employed by Herman Melville in crafting Moby Dick.

In his blog, Jenkins mused about Soulja Boy’s precocity:

I can’t decide what fascinates me the most about this story: the fact that this teenager broke into the front ranks of the entertainment industry by using tools and processes which in theory are accessible to every other person of his generation or the fact that he has recognized intuitively the value in spreading his content and engaging his audience as an active part of his promotional process.

Jenkins did not address the actual lyrical content of Soulja Boy’s music, and the actual ideas being packaged in the catchy beat and the playful dance steps. The content wasn’t the point of the presentation. The lyrics offer the kind of puerile vulgarity one might expect from a boy who is trying to impress his peers with stories about his sexual prowess and toughness. “Crank Dat” includes such lines as:

“Soulja boy off on this hoe…

“Then Superman that hoe…”

“I’m jocking on your bitch ass

And if we get the fighting

Then I’m cocking on your bitch ass…”

The lyrics reflect the cliches associated with the worst of hip-hop: degrading women while declaring dominance over other males by feminizing and threatening them. When Soulja Boy released “Crank Dat,” he was a 16-year-old high school student, and the song was spread largely by other teenagers. The character that Way portrays in the video is the stereotypical black male hip-hopper: hypersexual, prone to violence, gaudily attired. But the implausibility of the lyrics suggest that, like most amateur writers, Way is imitating what he has heard or gleaned from listening to others, not writing from life experience.

Jenkins showed videos of smiling teenagers and young adults bouncing on one foot, cranking their arms and lunging forward to make the “Superman” gesture.

In conversations with other conference participants, I seemed to have been the only person who was profoundly disturbed by the content that Way, AKA Soulja Boy, his minions, and ultimately, his record company were spreading. In part, I later learned, that was because many of my colleagues weren’t familiar with the lyrics. There was also the fact that “Crank Dat” was only another in a long list of songs, cartoons, games and other media content that they knew kids were exposed to, and it wasn’t the worst thing most kids would be exposed to. And after all, it’s not as if vulgar or even racially stereotypical music originated with remix culture.

I probably sounded like the scolds of the 1950s yelling about rock and roll, or the highbrows at the beginning of the 20th century inveighing against comic books and “pulp” novels. The Republic was still standing. I’m sure some thought I needed to smooth out that bunch in my panties and move on.

Or maybe not. The practice of analyzing form and distribution apart form content sits well within the tradition of media studies, going back to Marshall McLuhan’s declaration that “The Medium is the message,” and in rhetorical terms, “The medium is the massage.” However, I find Kathleen Welch persuasive when she argues that rhetorical analysis of both content and delivery is important to understanding the social justice implications of modern communications. If one follows the history of remixing trail of “Crank Dat,” one finds that its commercial success, facilitated by social media, led to the song being played in venues that would have been unimaginable in earlier times.

For example, a few months earlier, I had been sent a link to another performance of the song by a frustrated colleague and fellow member of the National Association of Black Journalists. It seemed that someone thought it would be fun to liven up a New York local morning traffic report with a performance of the song. The traffic reporter, Jill Nicolini, was part of the morning news “happy talk” format. A former Playboy bunny and occasional reality TV star, she routinely drafted men to dance with her after detailing the morning’s jams, delays, and alternate side-of-the-street parking rules. On this particular morning, she summoned Craig Treadway, the co-anchor, as her dance partner.

The Dancing Weather Girl – Watch more Funny Videos

The most telling moment for me was when Treadway broke into a tap dance. What was Treadway’s shuffle? And what do we make of the black male crew member bunny-hopping in the background?

I don’t know Mr. Treadway, Nicolini or any of the other members of that newscast, and I have hesitated for more than a year about writing this post because I’m not trying to cast aspersions on him or any other cast member of the show. If this post does that, I apologize in advance. They were doing their jobs, and perhaps they even had some fun. What I am trying to probe, as delicately as possible, is the meaning of the moment for journalistic norms in the age of remix culture.

Of course, the packaging of local television news as entertainment has been going on for a long time. A quarter-century ago, Neil Postman demonstrated the emerging parallels between the television news show and a television show designed as entertainment in his book, Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in an Age of Entertainment (Penguin, 1985.):

“If you were the producer of a television news show for a commercial station, you would not have the option of defying television’s requirements…. You would try to make celebrities of your newscasters…. You would have a weatherman [sic] as comic relief, and a sportscaster who is a touch uncouth (as a way to relate to the beer-drinking common man.) You would package the whole event as any producer might who is in the entertainment business.

“The result of all this is that Americans are the best entertained and quite likely the least well-informed people in the world….” (p. 106)

I came of age professionally during the early 1980s, so as a news consumer and media professional, I understand the pecking order of news shows. The anchor might smile and exchange some banter, but the anchor stayed dignified. I wasn’t thrilled at Nicolini’s shtick, but I understood it for the reasons Postman described. What I wasn’t ready for was an anchorman to be drawn into the clowning. It is very likely that what stuck in my craw was the sight of Treadway, who probably had to endure a great deal to attain an anchor desk in a major market, pulled out of the role on which, traditionally, his credibility rested.

There is one sense in which the problem is entirely mine, because it represents a collapsing of norms my generation of media professionals can’t quite stomach. It has become clear in recent years that there is a great deal of skepticism about the kinds of conventions that journalists traditionally adopt, whether it be certain standards of decorum, or a studied modesty about stating their political views. Even a growing number of journalists reject that last standard.

Then, too, there is the shifting calculus of racial symbolism to consider. Surely, the sight of a black man dancing alongside a young white female in 2008 does not mean what it meant in my childhood during the 1960s. In those days, such a sight was restricted to Shirley Temple movies. Treadway and Nicolini’s performance occurred the same year that a man with an African father and a wife descended from slaves won the White House.

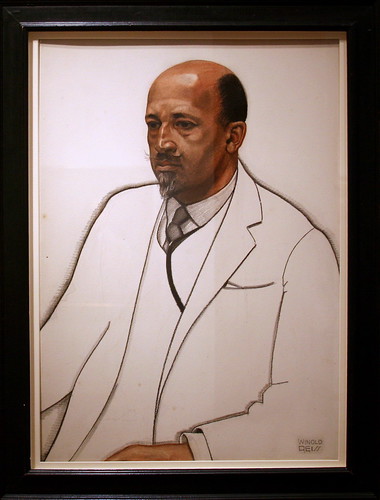

It’s unlikely that WEB Du Bois would have approved of SouljaBoyTellem’s art, or much of hip-hop, for that matter. The pioneering scholar, editor and activist hoped that those African Americans who gained access to the instruments of culture making would infuse high culture with the gifts of Africa. For him that meant spirituals (delivered Jubilee-style, of course) the vibrancy of traditional African art and artisanship, the nuanced poesy of a Jessie Fauset or Countee Cullen, with the occasional swinging riff from the deceptively accessible Langston Hughes. In his definitive essay on aesthetics, The Criteria of Negro Art, he implored:

“If you tonight suddenly should become full-fledged Americans; if your color faded, or the color line here in Chicago was miraculously forgotten; suppose, too, you became at the same time rich and powerful; — what is it that you would want? What would you immediately seek? Would you buy the most powerful of motor cars and outrace Cook County? Would you buy the most elaborate estate on the North Shore? Would you be a Rotarian or a Lion or a What-not of the very last degree? Would you wear the most striking clothes, give the richest dinners, and buy the longest press notices?

“Even as you visualize such ideals you know in your hearts that these are not the things you really want. You realize this sooner than the average white American because, pushed aside as we have been in America, there has come to us not only a certain distaste for the tawdry and flamboyant but a vision of what the world could be if it were really a beautiful world; if we had the true spirit; if we had the Seeing Eye, the Cunning Hand, the Feeling Heart; if we had, to be sure, not perfect happiness, but plenty of good hard work, the inevitable suffering that always comes with life; sacrifice and waiting, all that — but, nevertheless, lived in a world where men know, where men create, where they realize themselves and where they enjoy life. It is that sort of a world we want to create for ourselves and for all America.”

Part of Jenkins’ point is that participatory media expands the ranks of the tastemakers beyond Hollywood elites, intellectuals, and activists. Jay Rosen has been saying similar things about the shift to participatory journalism in essays such as The People Formerly Known as the Audience.” But when the ethos from which these new media products emerge can be tainted by values that are corrosive, a critical perspective is necessary.

In her essay, “Learning the 5 Lessons of Youtube: After Trying to Teach There, I Don’t Believe the Hype,” Alexandra Juhasz makes the argument that corporate dominance of this major media sharing site has turned do-it-yourself culture into a tool for replicating ideas and values that are fundamentally anti-democratic. In particular, she and her students found that depictions of African Americans that reinforce vulgar race and gender stereotypes are more popular, and thus more prominently featured, than those promoting more positive images or cultural critique.

And this is part of my concern, even as I contribute to this participatory culture and teach students to do it as well. The uncritical replication of negative images of black males is particularly vexing, because it undermines the effort to transfer of positive values from one generation to the next. In some ways, the current environment is arguably more challenging than the pre-Civil rights era, because in those days, there were alternative, black-controlled civic institutions that promoted images that countered the stereotypes of the dominant culture. Byron Hurt’s 2008 mini-documentary demonstrated Barack Obama’s rise exposed a deep-seated confusion and ambivalence about the possibilities of success, respect and power for black men in an era that is supposed to be “post-racial:”

I thought about this ambivalence as I watched clips from DeAndre Ramone Way’s videoblog, which has since been removed. He has been known to talk about his interests in art, education, and business along with his “beefs” with other rappers, his jewelry and his cars. Pop culture never was a good place for a complicated persona. When pop culture goes “spreadable,” what gets lost? Sometimes I’m afraid it’s the substance of a culture that we can’t afford to lose.