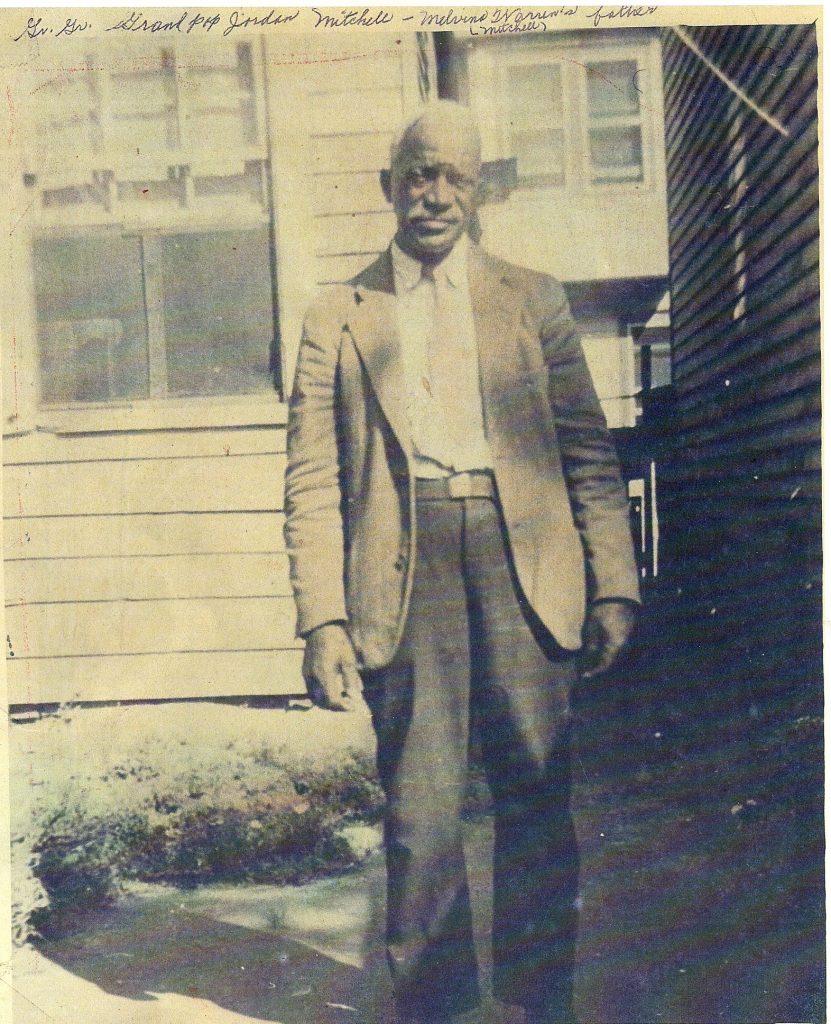

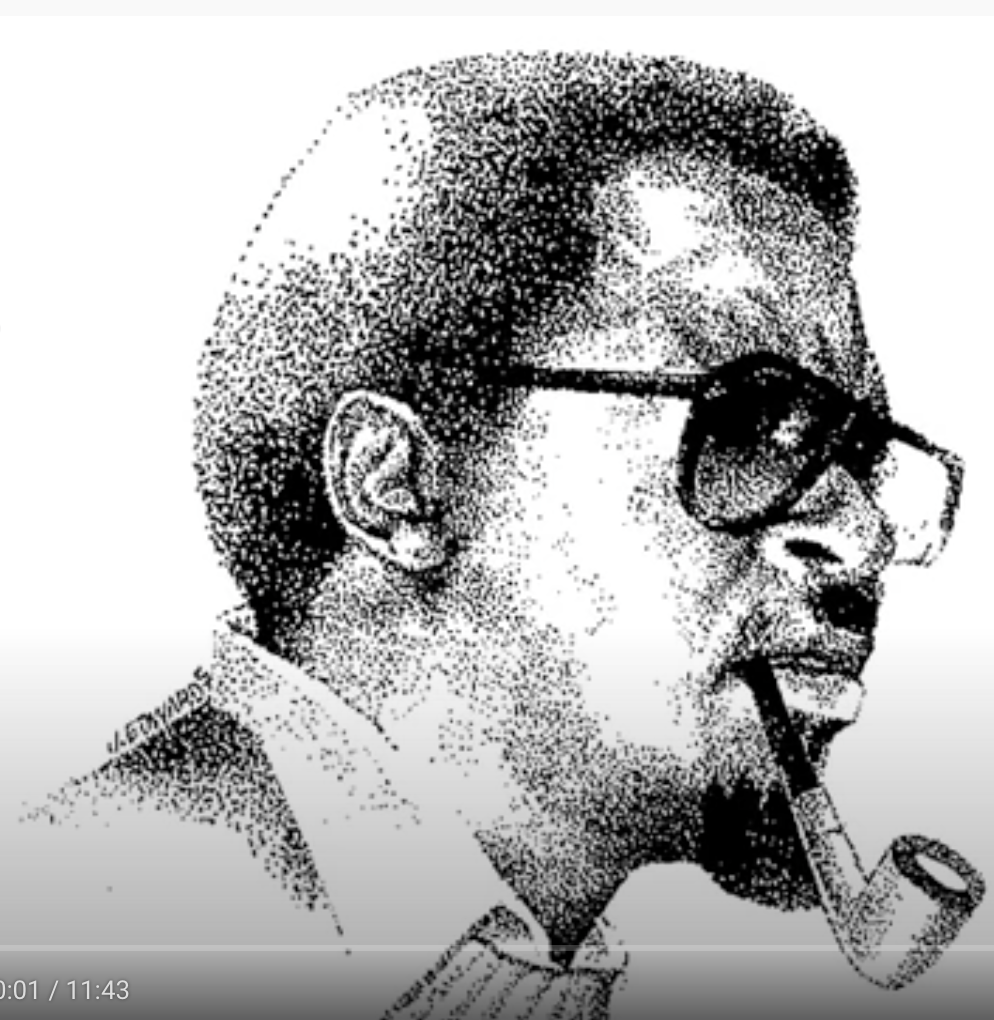

2021 Note: Donald T. Evans (1938-2003), was a notable playwright of the Black Arts Movement and a longtime educator at The College of New Jersey, as well as Princeton University and Princeton High School. He was also my friend. This poem is part of a tribute website that I built for him. (That site is only available now through the Internet Archive. As my TCNJ colleagues and I prepare to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the establishment of the Department of African American Studies, we’re collecting material for the celebration as well as for the archives. This small tribute remains meaningful to me. Below this poem, there are resources to learn more about Don Evans, a video of one of his plays a musical tribute from his children: Todd Evans, Rachel Marianno and Orrin Evans leading the Captain Black Big Band. You can also check out the Facebook page for the Don Evans Players, led by his son Todd Evans.

Once, dear Don, I danced with you

A slow and easy bop back to shared spaces, different times

You were West Philly oldhead to my North Philly funk

I was a bridge note in your syncopated symphony

Do you remember that Sunday afternoon

When our feet traced touchstones and boundaries between us?

How we had learned to listen through the spaces and the silence

Like Miles floating over a Stanley Jordan groove

Our clasped hands held the memory of our mutual friend, Mike,

Who left before either of us got to speak peace to his fire.

He tripped because of your spin on Baraka

He fled me because I lacked his queer eye

Our shuffling feet, slide, step, step, slide

Your beat, my echo, like I was your flipside

While you remembered the past you didnít live in it

You could let go, go solo, do a spin and move on

Once, dear Don, I danced with you

And I learned that you let each of us have our own private Don-song

In mine, you are a favorite uncle at the family reunion

And we glide to a melody that has no end

- Kim Pearson, February 7, 2004

______________________________________

Obituaries

- New York Times

- Playbill

- Atlanta Journal-Constitution

- Boston Globe

- Trenton Times

- The Oregonian

- Indianapolis Star

- Charlotte Observer

Reviews and articles

- Catanella, Louis. “Pungent Production in New Brunswick.” (review of Crossroads Theatre production of One Monkey Don’t Stop No Show) New York Times. September 14, 1980. Section 11, New Jersey Page 20, column 5

- “Don Evans’s new comedy stirs up a crackling bouillabaise of fun, the Crossroads Theater is serving it in a prime fashion and audiences are eating it up with gustatory abandon. If all meals were this tasty, we’d be feasting before proscenium arches night and day. ”One Monkey Don’t Stop No Show” makes most culinary treats look like Melba toast….

- Preston, Rohan. ‘Lovesong’ is simply spellbinding. (review of Lovesong for Miss Lydia) Star Tribune (Minneapolis, MN). September 23, 2001.p 6B

- Great Black One Acts.” nytheatre archive 2000-01 Theatre Season Reviews has this to say about Don’s Sugar Mouth Sam Don’t Dance No More

- “Evans’s depictions of the lonely hearts inside and outside the rundown Chicago apartment where his story unfolds are stunning…”

- “Juneteeth Jamboree to fill three weekends” Louisville Courier-Journal announcement of upcoming performance of Don’s play, “Dancing with Demons.” June 2, 2002

- “Women on the Verge –Again.” (capsule review of production of “Love Song for Miss Lydia”) Southside Pride, Nov. 2001

- “It’s Showdown Time” (mini-review). Chicago Reader, Sept. 2003

- “From classics to cult classics, Chicago stages light up,” (overview of new plays in town). Chicago Sun Times, Sept. 7, 2003

Don’s Work

- Alice: Conversations with Alice Childress, Obsidian III: Literature in the African Diaspora, Volume 1, Number 1, Spring-Summer 1999 (Table of contents only)

- “It’s Showdown Time” play description with link to Amazon.com page for ordering

- The Theater of Confrontation: Ed Bullins, Up Against the Wall. Black-World. 1974; 23(6): 14-18

Don on Campus

- Guest Playwright. University of Delaware, 1988-99

- “Playwright hopefuls to have 10 minutes of NU fame” NU News (Northeastern University), 1998

Don’s Connections

- Black Theater Network

- Dan Allen, Oddplayers Productions

- Terrie “Ajile” Axam, Total Dancical Productions

Black Theater Resources

- Coleman, Stanley R. The Dashiki Project Theatre: Black Identity and Beyond (Doctoral Dissertation) Louisiana State University, 2003, This study focuses on the history of a black theatre company in Louisiana established by Ted Gilliam, but it contains a great deal of historical and contextual information on the Black Arts Movement, referencing work by Don Evans, Amiri Baraka, Ed Bullins and others.

- Walker, Victor Leo. The National Black Theatre Summit “On Golden Pond”–March 2-7, 1998 African American Review, Vol. 31, No. 4, Contemporary Theatre Issue. (Winter, 1997), pp. 621-627. This article describes the a pivotal meeting on the state of black theater featuring Don and other prominent artists.