Editorial note: I started this essay in 2018 as I was working my way into the ideas behind my current project-in-progress American Storyworlds. I’ve revised it 116 times and it’s still a work in progress. I’m publishing it now, in its imperfect form, as I’m starting to make that project public. Also, I chose not to engage the current attacks on race scholarship, because that is a separate argument and this is already a very long post.

Nations are built on narratives. So much of the turmoil in which we Americans find ourselves has to do with the battle for control of the historical narrative on which our civic life is built. Whether individually or collectively, the way that we remember history has important implications for the way we constitute community, assess media credibility, and conduct civic life. In the wake of profound political, social, technological, and economic dislocations since the end of World War II, generations of scholarship unearthing the suppressed history of oppressed communities have helped to undermine grand narratives of white supremacy and heteropatriarchy. They have also engendered backlash and cultural fragmentation.

In 1995, technical communications theorist Johndan Johnson-Eilola contemplated how networked, hypertext communications technologies would alter our ways of constituting identity and community. In an essay that was highly influential (and novel in form) for its time, he argued that we needed to understand this shift in the larger context of the shift from modernism to post-modernism and its concomitant loss of faith in the institutions, technologies, and social arrangements that were supposed to have put us on the inexorable path to progress. According to him, “Postmodernism can help explain such concepts as the rise of contract over permanent labor, the growth of global markets and information networks, interdisciplinary teams in business and industry, among other things. But we will gain productive and valued positions in the workplace only if we begin to understand these cultural developments in new ways.”

The backlash against both shifting circumstances and norms of discourse has been broad and deep: Hate crimes are on the rise; authoritarianism is resurgent. Violent protests over Civil War monuments, calls to change the faces on US currency, the debate over reparations for descendants of enslaved Africans, and arguments over social studies curricula are visible reminders of both our fragmented understanding of the past, and the divergent ways in which we harness the past to envision possible futures.

The historical narratives that frame our everyday lives come from our schools, our religious institutions, our civic and fraternal organizations, our families, the media we consume and the networks we create. Increasingly, they also come from information that is served to by opaque algorithms – search engines, social media platforms, and genealogy platforms that mine public records and members’ text, media, and DNA inputs to give subscribers a version of where they come from and to whom they are connected.

I’ve found that there are two sets of competing meta-narratives of American history: a dominant narrative held by many of the acknowledged descendants of (mostly European) voluntary immigrants, and a set of counter-narratives held by many descendants of the indigenous people and of those who were brought here involuntarily from Africa. I refer to voluntary immigrants to account for those who came to the United States of their own volition from Africa, Asia and Latin America believing that there would be greater opportunities for them than there were in their countries of origin. The narratives don’t map neatly on to facile narratives of liberal, conservative or progressive ideologies, which is why I personally find most of the discourse about political polarization and tribalism incredibly unhelpful.

The dominant narratives hold that the United States was founded on noble ideals of liberty and equality, and while we haven’t always lived up to those ideals, we’ve been on a path of inexorable progress. To them, the system is fundamentally sound, and anyone who works hard and plays by the rules will eventually succeed. Failure is usually assumed to be a failure of individual character, poor parenting, or a degenerate subculture.

The counter-narratives hold that like the Athenians of old, the Founders only intended for the blessings of liberty to be available to men such as themselves, using wealth they extracted from the property and labor of indigenous people, indentured people, women, and enslaved people. Any progress we’ve achieved toward becoming a real democracy has been the result of agitation, that agitation must continue. Abolitionist and suffragist Frederick Douglas told us,“If there is no struggle, there is no progress. Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.” Now, what that “agitation” should look like, what constitutes progress, and how any of this should be articulated are matters of considerable debate. One only has to ponder Associate Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas’ oft-cited identification with the protagonist of Richard Wright’s protest novel Native Son to understand that agreeing that there is a thing called racism that limits people’s life chances is a far cry from agreeing on what the response to that empirical reality should be.

Journalism’s limits in facilitating public conversations

Journalists play a role in the development of collective memory and national identity, and the ways in which historical memory affects intercultural relations, public policy and the body politic. As Elizabeth Le has demonstrated, journalists ground their news analysis in culturally-specific historical narratives. For much of American history, mainstream journalism has upheld the dominant narrative – a narrative suffused with a belief in Black deviance and the importance of ensuring that the expansion of rights and social benefits are restricted to those who are deserving. For example, in her 2014 book, Savage Portrayals: Race, Media and the Central Park Jogger Story, Natalie Byfield connects press participation in the rush to judgment of five Black and Latino teenagers wrongfully convicted for the brutal rape and beating of young investment banker to racist myths that justified 19th century lynchings. . Eric Deggans’ 2012 book, Race Baiter: How the Media Wields Dangerous Words to Divide a Nation, documented ways in which mainstream news and opinion media exacerbated prejudice and xenophobia. Amy Alexander’s 2015 memoir, Uncovering Race: A Black Woman’s Story of Reporting and Reinvention, connected the lack of diversity in mainstream newsrooms to their failure to reflect the diversity of the communities they covered.

Mainstream news publications’ efforts to go beyond the dominant historical narrative have gained some traction in recent years. For example, Ta-Nehesi Coates’ 2014 essay,”The Case for Reparations” traced the historical roots of housing discrimination in Chicago as an example of generations of policies and practices that stole wealth from African Americans. The article sparked wide debate leading to a Congressional hearing and support from Democratic presidential candidates.

In a 2019 interview with New Yorker magazine editor David Remnick, Coates said, “When I wrote ‘The Case for Reparations,’ my notion wasn’t that you could actually get reparations passed, even in my lifetime. My notion was that you could get people to stop laughing,” According to Coates, what’s needed is a thorough examination of the damage wrought by white supremacy, accompanied by “a policy of repair.” Even conservative pundit David Brooks agreed.

A diverse and inclusive American polity requires the creation of more effective face-to-face and virtual spaces that permit an honest reckoning with our divergent understandings of history. The creation of such spaces poses challenges to journalists, historians and civic media designers that have yet to be fully articulated. We haven’t fully reckoned with the ways in which “the people formerly known as the audience” use media technologies to construct their own knowledge frameworks, and the ways in the owners of those technologies and malign actors exploit exploit those efforts.

In the classroom, I have encouraged students to use research methods derived from journalism, history and African American studies to develop family and community narratives that inform a personal articulation of what it means to be American. I’ve then asked them to listen to other student and community members’ experiences to consider how their individual perspectives might be integrated into a collective vision of American identity. Students have responded positively to this approach, saying that it has broadened their understanding of their own identities in relation to others. These anecdotal experiences lead me to wonder whether there are ways that journalists and civic media creators might use similar methods to facilitate informed dialog and community building around historical memory.

Mediating family history

Genealogical research is one way that many of us construct personal knowledge frameworks. Over the last decade, the advent of such services as Ancestry.com and FamilySearch.org has accelerated that interest, with millions of people contributing records, photographs, family stories and DNA, giving rise to discourse communities in which evidence is shared and vetted among people who would not otherwise encounter each other. These massive databases have also attracted other interested parties, such as scholars and law enforcement, leading to debates over ethics and privacy in some instances.

Finding Your Roots, a television show on the PBS network hosted by Harvard University African American Studies scholar Henry Louis Gates, advances an optimistic vision of the potential of genealogical research to undermine prejudice:

“By decoding our DNA, and untangling the branches of our family, we’ll discover how blurred the lines that divide us truly are.” Henry Louis Gates, Finding Your Roots

“[W]e have more in common than we have differences, and color doesn’t mean a thing.” Joe Madison, radio host, on Finding Your Roots https://www.thecrisismagazine.com/single-post/2019/04/09/Radio-Host-Joe-Madison-Finds-His-Roots

With the expansion of digital archives and commercially-owned genealogy databases, I am alert to both the possibilities and dangers of these emergent technologies: algorithmic bias, surveillance and “sousveillance,” and the crafting of false, mythic histories in the service of ethno-nationalist ideologies. (Browne, 2014, Noble, 2016) At the same time, communities of practice such as the restorative narrative movement, the racial dialog work of David Campt and others, along with theorists such as Ramesh Srinivasan and Michelle Ferrier suggest design processes and computing architectures that might lead to the creation of constructive and non- exploitative spaces.

While I approach this topic from my own standpoint as an African American woman, I’m aware that many people with other backgrounds feel impelled to make similar explorations. Journalist, scholar and civic media entrepreneur Michelle Ferrier notes:

“The Signifying Quilt: A Patchwork-Type of Narrative“

As bell hooks suggests, the overall impact of postmodernism is that many other groups now share with black folks a sense of deep alienation, despair, uncertainty, loss of a sense of grounding even if it is not informed by shared circumstance (hooks, 2481). So the task of my narratives was and continues to be to provide a space for those “shared sensibilities” that cut across gender, race, class and sexual practice.

Communication scholar Peter Lunt has observed that explorations of family history have become one popular means of addressing this dislocation:

“[T]he idea of finding out about oneself through an exploration of the character and lives of ancestors is a growing social practice reflected in popular culture. Tracing one’s personal traits through past family members and extending the sense of family and identity back in time potentially enriches personal identity and link personal, social and cultural memory.”

Lunt, P. (2017). The media construction of family history: An analysis of “Who do you think you are?” Communications: The European Journal of Communication Research, 42(3), 293–307. https://doi.org/10.1515/commun-2017-0034

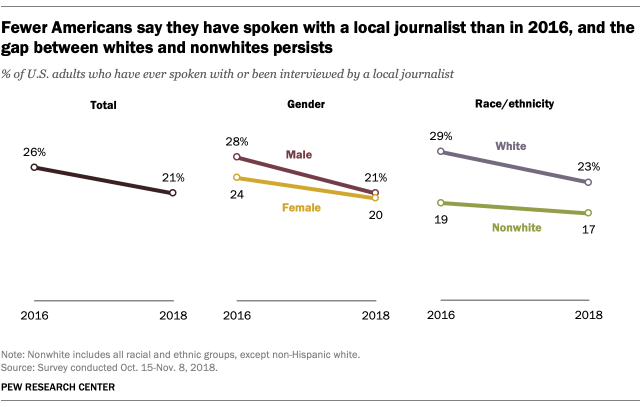

For all of the import that these meaning-making and community-building practices have for the people who engage in genealogical research and consuming media about it, attention from journalists has been limited. In a 2008 article for Memory Studies, journalism historian Carol Kitch notes that until recently, journalists and scholars have held the mundane interests and lore of their audiences in low regard, thinking “we are the ones who know what matters most.” However, the collapse of traditional journalism’s business model and the critiques of extractive journalistic practices advanced by such critics as Lewis Raven-Wallace have created a new openness to new ways of understanding and centering community information needs and collaborating with communities to meet those needs. (For examples, see Andrea Wenzel, Freepress, Sue Robinson) Might these epistemic communities of family historians be allies in journalists’ efforts to report true stories that are considered useful and trustworthy?

My interest in these possibilities are informed by my own experiences as a cisgender, middle-class, African American woman three generations removed from slavery, educated in elite, predominantly white universities, with a professional background as a journalist and professional communicator in corporate, non-profit and academic settings. My efforts to make sense of the places in which I found myself led to explorations of family and community history that made me acutely aware of the ways in white supremacy, patriarchy and class bias distort the knowledge that is available to us. But they also make me aware of the liberating potential of recovered ancestral memory.

As I’ve written elsewhere, I was a college student when I first became fascinated with researching my family history while watching the 70s miniseries “Roots” with my father. Although I knew that we had descended from enslaved people, I was shocked when my father casually remarked that his grandfather had not only been enslaved — he’d talked about seeing people get whipped and having their feet chopped off for running away. None of my elders had talked about knowing any family members who had been enslaved. I had no idea that I had grown up with a grandmother, great-aunts and great-uncles who were children of enslaved people. Roots loosened their stammering tongues. I had been interested in African American history since elementary school, but now I was animated by the possibility that there might be a way to understand how my family and I were, as Helen Epstein put it, “possessed by a past that [we] had not lived.”

As Roy Campanella II noted in an appreciation of Haley after the latter’s sudden death in 1992, Roots was an “astonishing feat of genealogical detective work across three continents” that began with his grandmother’s oral history about “the African” and reportedly resulted in Haley being able to trace his family back to the Gambian village from which his ancestor had been abducted. “In doing so,” Campanella added, “he told the story of 30 million Americans of African descent, made it possible for us to share in his profound journey of discovery, and won our admiration and respect.”

Or perhaps he told the story that we wanted to believe – that somehow it might be possible to reconnect what had been sundered by slavery and circumstance, and by so doing, build a high ground on which we too could stand, hoist our babies to the stars and declare, “Behold! The only thing greater than yourself!” While Roots was a pop culture phenomenon and a media sensation, historians and professional genealogists cast doubt on the accuracy of the the book. A plagiarism lawsuit was filed and settled.

Historian Donald Wright has reported that the power of Roots and resulting miniseries has been such that Haley’s putative ancestral village remade itself in the image of the novel and marketed itself as a tourist attraction. Despite its failings, the Roots phenomenon did help inspire a new generation of African American historians and genealogists to take up the task of finding and popularizing methods for excavating family histories. These included the founding of the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society in 1977, as well as the publication of Charles Blockson’s guide, Black Genealogy, the same year. Blockson’s work was part of larger movement of black scholars and activists – black studies, ethnic studies and women’s studies were fledgling fields during my college years. By placing the experiences and intellectual production of oppressed people at the center of their analysis, these scholars theorized new knowledge frameworks – such as intersectionality, queer theory and feminist theory – for understanding ourselves and our relationships to each other.

Learning to “read against the archive”

Blockson’s book gave readers lessons in archival research and his life’s work of archive-building sought to correct gaps, omissions and distortions in the archival records. His work was part of the intellectual ferment of the 1960s and 70s, but it echoed calls by earlier generations of social scientists, historians to undertake systematic studies of the lives African Americans with the goal of developing policies to support their progress in the years after Reconstruction. As far back as 1898, W.EB. Du Bois, considered one of the founding fathers of black studies, opined:

cf Earl Wright, II and Thomas Calhoun, “Jim Crow Sociology: Toward an understanding of the origin and principles of black sociology via the Atlanta Sociological Laboratory“

Americans are born in many cases with deep, fierce convictions on the Negro question, and in other cases imbibe them from their environment. When such men come to write on the subject, without technical training, without breadth of view, and in some cases without a deep sense of the sanctity of scientific truth, their testimony, however interesting as opinion, must of necessity be worthless as science ([1898] 1978:76)

Sociologist Elliot Rudwick supported Du Bois’ indictment:

[T]he “general point of view” of the first sociologists to study the black man was that “the Negro is an inferior race because of either biological or social hereditary or both.” . . . These conclusions were generally supported by the marshalling of a vast amount of statistical data on the pathological aspects of Negro life.In short, “The sociological theories which were implicit in the writings on the Negro problem were merely rationalizations of the existing racial situation.” (P. 48)

cf Earl Wright, II and Thomas Calhoun, “Jim Crow Sociology: Toward an understanding of the origin and principles of black sociology via the Atlanta Sociological Laboratory”

The fruits of this labor are evident throughout the academy and among serious journalists. There lies, at its heart, an expanded definition of intellectual activity coupled with the adaptation of both quantitative and qualitative research methods. Speaking of the evolution of black studies, sociologist Abdul Alkalimat says:

Black intellectual history is rich and dynamic. It is constituted by the rich intellectual culture of black people, encoded in the political culture of everyday life. This includes messages in the quilts, in drum beats, and in children’s stories, popular music, presentation of self strategies and esthetic rituals in hair, dress and body motion, style and plain old conversation in the vernacular.

eBlack, Reflections and Research Practices, 2000

Commenting on the methods employed by Du Bois and other sociologists, historians and anthropologists who shared his commitment to antiracist scholarship, Alkalimat identifies five research practices at the core of their scholarship:

- Compiling bibliographies

- Archiving

- Building data sets

- Setting up sustainable organizations

- Theory building

Before the 1990s, most of this work was generally ignored or dismissed by mainstream institutions, journals and publications. Du Bois’ Philadelphia Negro, published in 1899, is now recognized as “America’s first major empirical sociological study” – combining ethnographic interviews, comprehensive data collection and analysis, archival material, data visualizations, and participant observation. Du Bois and his colleagues extended that methodology to the design and execution of the Atlanta University Studies, a series of systematic examinations of various aspects of black life conducted from 1897-1914. However, C.W. Anderson notes that Du Bois and other reform-minded urban sociologists “were systematically erased from the remembered history of sociology for more than a hundred years.” Instead, Robert Park and his colleagues at the University of Chicago were credited with the creation of the first laboratory in urban sociology. In contrast to Du Bois and his contemporaries, the “Chicago School “ sociologists favored theory over empiricism, and statistical sampling over comprehensive data collection. (Also see Wright, 2016)

Had I spent my undergraduate years at a historically Black college or university (HBCU), there’s a chance that I would have learned about DuBois in my classes instead of seeking him out on my own. There’s a chance that I might even have learned about Dr. Carter G. Woodson’s Association for the Study of African American Life and History with its Journal of African American History. However, I matriculated at Princeton. Consequently, the canonical sources I was trained to consult and the methods of inquiry I was taught were created by people who were unlikely to have been exposed to scholarship created by people of color. The canonical secondary sources penned by the people WEB DuBois derided as “the car-window sociologist[s]” either do not know or do not credit Black scholars and my community’s ways of knowing.

A case in point: In the semester before I learned about Great-grandfather, I did an independent research paper on the Minority Enterprise Small Business Investment Company (MESBIC) under the direction of Prof. Barbara Nelson, then on the faculty Princeton’s school of public policy and international affairs. MESBICS were investment firms licensed by the federal Small Business Administration that offered both equity and debt financing to entrepreneurs of color. SBICs still exist, but the MESBIC program went by the wayside some time ago. My interest stemmed from growing up in Philadelphia, where Rev. Leon Sullivan‘s church was doing transformational work through its job training center, affordable housing development, shopping center and a foray into light manufacturing.

It was these tensions – between what we were taught and what we lived, between what was prescribed and what we needed, between the interests we were being trained to uphold and the needs we hoped to address, that propelled the agitation for new academic disciplines that built on the work of such institutions as Carter G. Woodson’s Association for the Study of African American Life and History, the Freedom Schools and the Highlander Folk School. These were institutions that valued scholarship and rigor in the ultimate service of social justice. Pedigreed scholars partnered with organic intellectuals, journalists, and activists to combat miseducation and engender progressive change.

Thus, the first generation of African American Studies scholars didn’t just challenge the racist distortions and omissions of the established disciplines – they were championing a model of scholarship that the had already been rejected. As Abdul Alkalimat has noted, as African American Studies evolved, many of its leading scholars would also eschew community engagement and activism in favor of more traditional teaching, publishing and service. It is, however, this set of research practices and community engagement that holds promise for community-centered journalists today.

Finding my roots

Like most people, my own foray into genealogy was a personal quest to make sense of myself by understanding my family’s past.

Digging into census records and probate records made any pretense to dispassionate inquiry impossible. Because our existence was most frequently recorded in relation to our property value, with only as much detail as was required for the pecuniary or political purposes of the people who called themselves our masters. The slave census schedules only include the owner’s names, so I was forced to rely on family lore to find the records that most likely referred to my Great-grandpa and his family. Seeing that document was a gut punch, as I explained in this 2016 interview with Princeton University undergraduates studying the relationship between the University and slavery.

Facts, methods and mysteries

Genealogical research becomes guesswork when the subjects of the research were considered unimportant by the people who generated the records. Oral histories, family photographs and documents are essential, as is contact and information-sharing between scattered branches of the family. My father’s generation started organizing reunions in the 1980s to ensure that my generation would know his generation’s first cousins, and we could begin to document the family story. Two cousins built an extensive family tree that we published and disseminated in 1990. One of my cousins even went to Utah to dig into the Mormon archives there. In 1988, I teamed up with a photographer to create a photo essay exhibit that traced the arc of our family’s story from slavery to the late 1980s. So we had a great deal of information even before the advent of Ancestry.com and similar databases.

The advent of computerized genealogy search services has been both a blessing and a challenge. The cousins who had done the original genealogical research became our fact-checkers. Census records often misspelled names: Jordan Mitchell is variously referred to as Jordin and Jerfin and he’s given a non-existent son named Grover, who we’ve determined is actually George. Nelson Mitchell’s son Frayforan doesn’t appear at all, but his sister’s testimony led us to understand that he had been renamed either Frank or Frazier in various records, including his death certificate. One grandfather doesn’t show up as a member of the household in which we know he was raised – except, possibly as a “servant” in the 1900 census. And if that listing is accurate, his birthday was actually three years earlier than we thought. According to my uncle, that’s a possibility – he said my grandmother told him that my grandfather chose a birthdate because he wasn’t sure when he was born. Poor rural Georgians didn’t commonly have birth certificates. One of my uncles, born in 1921, learned that when he went to apply for a passport.

Between the oral histories and uncertain documents, this is what I’ve been able to confirm about my father’s family. My paternal great-great grandparents were Holland and Judy Priscilla Mitchell from Hancock County, Georgia. Holland was born around 1811; Judy Priscilla was born around 1824. According to my late Cousin Ella, either Holland or Judy Priscilla’s father might have been an Indian who was forced out of Georgia during the Trail of Tears. She didn’t know his name. The census records say that their parents were Negroes. Their slave master was a man named John HW Mitchell. According to their son Jordan, my great-grandfather, Holland was a barrel maker, a craft requiring considerable strength and skill. According to their daughter Elsie, all the slaves on the Mitchell plantation had to eat their meals from a horse trough. As small children, they saw whippings, beatings, mutilations. Elsie recalled that when news came that the Civil War had ended, they ran about the plantation shouting, “We are free!”

Jordan married Martha Holsey. Her father worked for Mrs. Linton Stephens – the wife of the former state Supreme Court judge and the sister-in-law of Jefferson Davis’ Vice President. It appears Lucius Holsey, bishop of the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church, was a cousin. Lucius’ white father acknowledged him and that left him in a somewhat privileged position. He became a leading advocate for Black rights in the wake of the Atlanta riots of 1906. One of Elsie’s sons might have gone into ministry and advocacy work with him in Atlanta. Most members of the family were farmers, though.

Jordan’s youngest daughter, Mattie, married Jesse Pearson. Not long before their marriage Jesse lived with his sister Christine and her husband Abraham. They worked on land owned by Abraham’s father, Guy. Abraham’s sister, Nettie, was a wardrobe mistress for Ma Rainey. She married Rainey’s piano player, who was known as Georgia Tom. The young couple moved to Chicago, where Nettie died in a car accident that also the baby she was carrying. Her heartbroken young husband turned wrote “Precious Lord, Take My Hand,” and Thomas A Dorsey became one of the founding fathers of Gospel Music.

Meanwhile, my mother told me that I should investigate her father’s lineage, although I didn’t make headway there until after her death in 2009. My grandfather, Owen Barnes, Sr., was drafted into World War II when my mother was a toddler. He died in a VA hospital when she was seven. She never got to know him, but she was right that his family was fascinating. Of course, by the time I started digging into his story, I had the benefit of Ancestry.com and other genealogical databases, and that would lead to a few surprises.

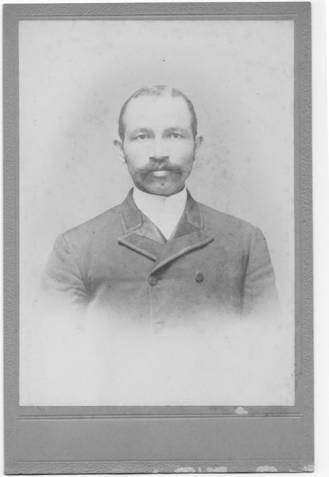

My grandmother kept a family Bible that had the name of Owen’s parents, so that was my starting point. Fortunately, there’s a sizable group of relatives on Ancestry researching this family. Through their shared trees, photos, census records and death certificates, I learned that, Owen Barnes, Sr.’s maternal grandparents, Lewis and Mary Smith McLaine, were born in 1847 and 1852, respectively, in Cecil County, Maryland. In the photos below, they both look to be of mixed race. Although we have the name of Lewis’ parents, it’s not clear what happened to them. By the time of the 1860 census, he is living with an unrelated group of people. He is, however, listed as a free person. He became a cobbler.

Mary’s father, Alfred G. Smith (1811-1884), was a millwright, and the 1870 census identifies him as a mulatto. Cecil County Maryland is home to the Perry Point Mansion House and Mill. It’s likely that Alfred worked there. The grist mill had been built by Henry Stump (1734-1814), whose daughter Mary married a man named Hugh Smith (1754-1839). Hugh Smith’s father, Thomas, had managed the mill, and Hugh took it over after his father died. They had a son named William, born in 1785. Ancestry’s algorithm suggested that William might have been Alfred’s father. If that’s correct, then part of the family’s lineage goes back to at least 14th century England.

At some point, Alfred and Mary found their way to Haverford, Pennsylvania, where they started their family. That’s where my great-grandmother Elva was born. Elva’s brother, Smith McLaine, married a schoolteacher who had, at some point, worked for the Institute for Colored Youth, now known as Cheyney University. Two of their daughters became STEM pioneers – although their contributions have only recently been acknowledged. I didn’t know these women, although I recall my mother referring to two of my grandfather’s cousins who were still living in the Philadelphia area. She couldn’t remember their names and I couldn’t find them before they died.

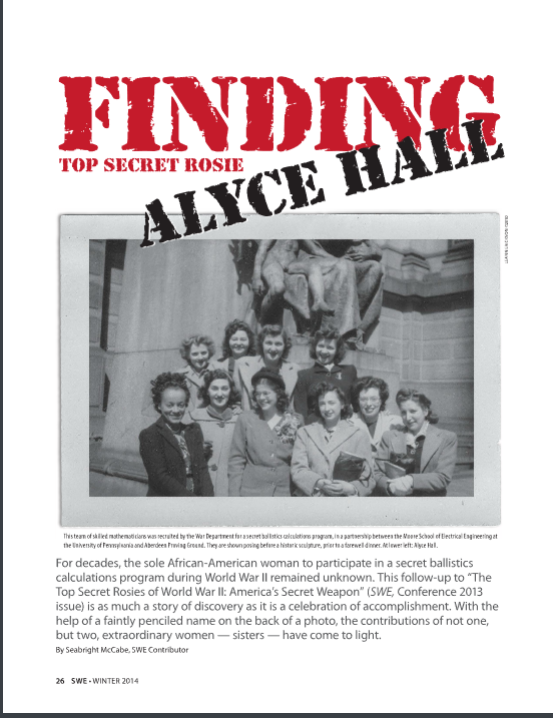

The daughters, Alyce Mc Laine Hall and Alma Mc Laine White, were gifted at math. A 1928 graduate of West Chester University, Alyce was hired by the War Department to be part of a secret team of women mathematicians who calculated the ballistics of missiles during World War II. She was the only African American on the team. They were known as the Top Secret Rosies, as in Rosie the Riveter. At war’s end, Alyce eventually returned to her earlier career as a math teacher in Philadelphia, but Alma had a 40 year-career working for the Navy.

Documentary filmmaker LeAnn Ericson first learned about Alyce Hall in the course of producing her 2010 film, Top Secret Rosies: The Female Computers of World War II. She interviewed four of the ten women who had been part of the project, but all she was to learn about Alyce was her name. As this Winter, 2014 article in the magazine of the Society of Women Engineers explains, Ericson eventually found and interviewed Alyce Hall’s family with the help of forensic genealogists. That’s how she learned about Alma’s accomplishments as well.

I’ve been in touch with a distant maternal cousin who did know these women. He credits them as a formative influence on his own decision to become a scientist. My grandfather died long before I was born – hence my mother’s sketchy memory of his cousins. The sisters lived into the early years of the 21st century, so it’s possible that members of our branch of the family could have gotten to know them. I don’t know how we became disconnected from grandfather’s family. Now that we have this history, I think about how it might help my younger cousins think more expansively about their own life possibilities.

The meaning of all this

In the novel Their Eyes Were Watching God, Zora Neal Hurston’s character Nanny says, “Us colored people is branches without roots, and that makes things come round in queer ways.” Rootlessness is endemic in this postmodern age. Journalists trained in such disciplines as African American Studies and emerging practices of community-centered journalism and restorative narrative are equipped to collaborate with communities as they seek to forge individual and collective understandings of the past that permit constructive visions of the future. My next projects will be devoted to understanding what that might look like in practice.

Notes

- See W.E.B. Du Bois’ recollections of his student days at Harvard and his short story, Of the Coming of John, Harold Cruse’s contentious Crisis of the Negro Intellectual and its critics, Jill Nelson’s Volunteer Slavery: My Authentic Negro Experience, Nell Painter’s Regrets, Pamela Newkirk’s Within the Veil, Amy Alexander’s Uncovering Race: A Black Journalist’s Story of Reporting and Reinvention and the admirable collection,Presumed Incompetent for examples of the ongoing salience of this issue in both journalism and the academy.)