In the wake of widespread protests against police violence during a time when the Covid-19 epidemic’s racially disparate impacts highlight the inequities in our health systems and economy, academics are having searching conversations about how we talk about racism with our students. It has also elicited painful testimony about the experiences of college educators who have dared to teach about racism. Scholars in African American Studies, Ethnic Studies and related disciplines have been studying and teaching about racism for decades, often at great professional cost and without adequate institutional support. Faculty outside of those areas who hadn’t seen a connection between what they teach and systemic racism are making connections and searching for ways to respond. Any attempt to address how we should teach right now must acknowledge that while some faculty are approaching this subject with idealism, interest, and concern about getting it right, others – disproportionately faculty of color – are weary and wary.

Much of what’s been offered to faculty focuses on strategies for talking about race and racism in class. There’s advice from civil rights educators, webinars, and tips from the Chronicle of Higher Education. But Brenda Leake, director of the Center for Teaching and Learning and professor of Education at The College of New Jersey, cautions faculty who are looking for simple solutions to the problem, such as adding a learning goal to a syllabus along with a related reading or activity. Individually, and collectively, faculty need to be clear about what they are trying to accomplish in talking about race, to know the content and to have instructional strategies matched to the content and the students.

It’s a false separation to say, oh, here’s the curriculum without having instructional strategies to deliver or to have instructional strategies, knowing techniques and strategies for instruction, but not really understanding the content. Well, that it’s a false separation. If you want to talk about effective learning scenarios, you have to understand both. You can have content that’s wonderfully rich in terms of its potential, but if it’s delivered ineffectively or in ways that counter the content that’s being taught, then it’s really a waste.

Personal interview, June 29, 2020

That’s why some scholars who work on race argue that professors who haven’t studied these issues shouldn’t be teaching them. Instead, they argue, students should be encouraged to take classes in African American Studies and related fields, and college should provide the support and recognition that work deserves. Ohio State University economist Trevon Logan made this argument in a recent Twitter thread about his discipline’s failure to value this type of scholarship. (See this cautionary tale about economist Lisa Cook’s decade-long struggle to publish her “groundbreaking” work on the role of racial terrorism in suppressing Black innovation between 1870-1940 for an example of that failure.)

Logan’s perspective has particular salience amid reports that in the face of the financial crisis precipitated by the Coronavirus pandemic, academic leaders are cutting programs in African American Studies, Women’s and Gender Studies and Ethnic Studies, as well as contingent faculty, where women and people of color are over-represented.

Meanwhile, there are real consequences to producing graduates who are allowed to think that race and social justice issues are extraneous to their fields of study. The recent controversy over a respected science publisher’s reported acceptance of paper whose authors claimed they’d developed a system to predict “criminality” based on facial images is just one of many examples of the problem. As an open letter signed by more that 2,000 scholars from diverse disciplines argued:

“This upcoming publication… is emblematic of a larger body of computational research that claims to identify or predict “criminality” using biometric and/or criminal legal data.[1] Such claims are based on unsound scientific premises, research, and methods, which numerous studies spanning our respective disciplines have debunked over the years.[2] Nevertheless, these discredited claims continue to resurface, often under the veneer of new and purportedly neutral statistical methods such as machine learning, the primary method of the publication in question.[3] In the past decade, government officials have embraced machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI) as a means of depoliticizing state violence and reasserting the legitimacy of the carceral state, often amid significant social upheaval.[4] Community organizers and Black scholars have been at the forefront of the resistance against the use of AI technologies by law enforcement, with a particular focus on facial recognition.[5] Yet these voices continue to be marginalized, even as industry and the academy invests significant resources in building out “fair, accountable and transparent” practices for machine learning and AI.[6]] “

Coalition for Critical Technology. “Abolish the #TechtoPrisonPipeline: Crime prediction technology reproduces injustices and causes real harm” Medium, June 23, 2020

Here, the Coalition argues that computer scientists need to be better educated about the historical context and social implications of the work they do and the ways in which they do it:

Computer scientists can benefit greatly from ongoing methodological debates and insights gleaned from fields such as anthropology, sociology, media and communication studies, and science and technology studies, disciplines in which scholars have been working for decades to develop more robust frameworks for understanding their work as situated practice, embedded in uncountably infinite[30] social and cultural contexts.[31]

Coalition for Critical Technology. “Abolish the #TechtoPrisonPipeline: Crime prediction technology reproduces injustices and causes real harm” Medium, June 23, 2020

Questioned by MIT Technology Review, the publisher, Springer Nature, said that the paper had actually been rejected during peer review. As reported, the Springer statement does not address the Coalition’s other demands – that the criteria used to evaluate the paper be made public, that Springer “issue a statement condemning the use of criminal justice statistics to predict criminality, and acknowledging their role in incentivizing such harmful scholarship in the past,” and that other publishers announce that they, too, will reject submissions employing similar methods.

Would more robust exposure to the kinds of scholarship that the Coalition advocates prevent such misconceived projects in the future? Computer science educators would need to be part of the conversation to find out. In a recent blog post, Mark Guzdial, a leading figure in computer science education, admitted he has a lot to learn: “I know too little about race, and I have not considered the historic and systemic inequities in CS education when I make my daily teaching decisions…. Let’s learn about race in CS education and make change to improve learning for everyone.”

The soul-searching isn’t limited to computer science. For example, the Journal of Chemical Education published a statement June 19, 2020 on Confronting Racism in Chemistry Journals. A related editorial calls on chemistry educators to do a number of things, including:

“Educate yourself and your co-workers on the scientific literature that shows how systemic and insidious bias is in science. Some valuable resources on both explicit and implicit bias can be found here: https://advance.umich.edu/stride-readings/. Use these data to refute claims that science is purely a meritocracy, that the playing field is inherently equal for everyone, and that scientists are being hired/promoted solely on their merits.”

Melanie S. Sanford, ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, XXXX, XXX, XXX-XXX

Publication Date:June 17, 2020 https://doi.org/10.1021/acscentsci.0c00784

Copyright © 2020 American Chemical Society

Ideally, faculty such as Guzdial who are beginning to learn about structural racism in their own disciplines would be able collaborate with relevant campus experts to ensure that racial literacy and a commitment to racial equity is reinforced across the curriculum. What I propose in this essay is that there are models of interdisciplinary collaboration that can be equitably deployed to deepen students understanding of institutional racism across the curriculum. The models I am going to discuss were developed as a result of research funded by the National Science Foundation over the course of the past dozen years, for the purpose of deepening students’ computational fluency and science literacy. (While I was and am part of these research teams, the opinions offered here are my own.) These models – Distributed Expertise and Collaborating Across Boundaries – provide structures for both reciprocal learning and grappling with real-world issues.

With proper institutional support -flexibility to schedule classes concurrently and logistical support for community engaged learning, for example – these research-based models could be implemented without perpetuating the marginalization of social justice scholarship.

1.Distributed expertise models

These models are intended to facilitate inquiry-based learning and cross-disciplinary collaboration in a way that does not require team teaching. Then collaborating courses have separate learning goals, deliverables, and grading. Below, I will include descriptions of these models, links to some of research that has been published, and a description of our current research project, which is entering its second year. I’ll follow this with some ideas of how the collaborations might work in practice.

What they are. From 2008-2013, I was part of a team led by Villanova University researchers Lillian Cassel and Thomas Way that developed and tested three models for teaching computing across departments and institutions. Our work was funded by NSF Award #0829616. These models were called Remote Experts with Local Facilitator, Cooperative Experts, and the Special Resource model.

Remote Expert Model. Under the remote expert model, one class with deeper expertise in a particular area contributes to a another class’s project, often at a different institution. In an example we described in this paper, game design students at Villanova contributed code to a game engine being designed at at TCNJ and TCNJ Interactive Storytelling students analyzed the story bible for the TCNJ game implementation class to identify plot holes before the story was implemented in code. The game implementation class gave the Interactive Storytelling class an interactive storytelling engine that the storytelling class used in order create their midterm projects. Then the Interactive Storytelling students shared their projects with Villanova software engineering students who did a code review.

Potential application: A chemistry class might have a unit in which students learn to detect contaminants in water. They might provide such an analysis to a class that investigates environmental justice or public health issues. The chemistry students would be exposed to the scholarship on the systemic failures behind such events as the water crises in Flint, Michigan, Newark, New Jersey and elsewhere. The environmental justice students would be exposed to a practical application of scientific research.

Special Resource Model. The Special Resource Model involves bringing in subject matter experts from a different field in to collaborate with the STEM class. The Gumshoe project, a collaboration between TCNJ professors Monisha Pulimood (Computer Science), Donna Shaw (Journalism) and Philadelphia Inquirer reporter Emilie Lounsberry is a great illustration of this model. (Lounsberry became a full-time faculty faculty member in the TCNJ journalism program after this project was published.) Lounsberry had been covering the Philadelphia courts for a long time, and had observed that many cases of firearms possession never seemed to go to trial. Shaw obtained court records of nearly 700 people arrested for unlicensed gun possession in January and February, 2006. A subset of these individuals were also accused of violent felonies. Pulimood’s students created a database to help her and her students manage the data. They tracked these cases through the courts and found that nearly half the cases were withdrawn by the DA’s office or dropped, that witnesses often failed to appear, and that only a small percentage of the arrestees charged with both illegal gun possession and violent felonies received significant jail time. Presented with the results, the Inquirer did its own analysis, reaching similar conclusions. Lounsberry and a team of reporters ultimately produced a four-part series that led to significant reforms in the Pennsylvania court system. You can read a detailed description of the project in this 2011 paper for the Special Interest Group for Computer Science Education for the ACM (SIGSCE).

Potential application. This model is well-suited to collaborations in such areas as journalism, education and public information. For example, chemistry or physics class could collaborate with a writing, education, or health communication class on producing material about climate change or environmental justice. Social scientists could collaborate with education majors or artists to produce works that elucidate issues related to race, power, privilege and trauma.

Cooperative Experts Model. The cooperative experts model differs from the special resource or remote experts model in that each the two collaborating classes are conceived as genuinely collaborating, as opposed to operating in a provider- client relationship. In this model, each class has distinct areas of expertise that they bring to the collaboration. Ideally, the classes are scheduled simultaneously, and there are periodic joint meetings at the beginning, middle and end of the project where students can brainstorm ideas and develop and implement team projects. This requires considerable communication and modeling between the instructors, but it can be very fruitful.

Potential application. Imagine a biomedical engineering class taking on “race correction” in medicine in collaboration with a class focused on some aspect of critical technology studies. Race correction is the practice of creating medical devices and treatment protocols that rely on algorithms that use race as part of their criteria, despite the fact that race is a social, not biological category that serves as a poor proxy for genetically-defined populations.This June 2020 New England Journal of Medicine article has a concise overview of the controversy, and this handy chart illustrates the scope of the problem. Drawing on the work of physiologist Lundy Braun, Ruha Benjamin describes one insidious outcome of employing race correction in a common medical device, the spirometer, when 15,000 asbestos workers filed a class-action workplace safety lawsuit against a major insulation manufacturer.

“[T]he idea [of] race correction [is] so normalized that there is a button that produces different measures of normalcy by race – the company made it more difficult for Black workers to qualify for workers’ compensation. Black workers were required to demonstrate worse lung function and more severe clinical symptoms than White workers owing to this feature of the spirometer…”

Ruha Benjamin, Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code, Polity Press, 2019, p. 286

This 1999 Baltimore Sun article confirms that the company, Owens Corning asked a judge to remove Black plaintiffs from the suit, even though their scores would have been accepted as indicating lung damage had they been white.

I can envision a collaboration in which the students interrogate the impacts of these practices, and perhaps consider criteria for more equitable tools. For example, the algorithm used to determine the likelihood of successful vaginal birth after a cesarean section known as the VBAC caculator, includes race corrections for both Black and Hispanic women. As this 2019 article from the Women’s Health Issues Journal notes, the inclusion of the non-biological category of race in the algorithm not only lacks scientific justification, it also evokes discredited ideas about the supposed anatomical differences between Black, white and Hispanic women. In an interview with the investigative reporting podcast, Reveal, the lead developer of the VBAC said the inclusion of race in the algorithm was based on empirical observation. However, the authors of the Women’s Health Issues article argue:

The danger of including race in this manner within a clinical algorithm is in implicitly accepting these categories as natural rather than historical and socially constructed. More often, race is included as a proxy for other variables that reflect the effect of racism on health: factors like income, educational level, or access to care.

Darshali Vyas, et. al. Challenging the Use of Race in the Vaginal Birth after Cesarean Section Calculator, Women’s Health Issues 29-3 (2019) 201–204

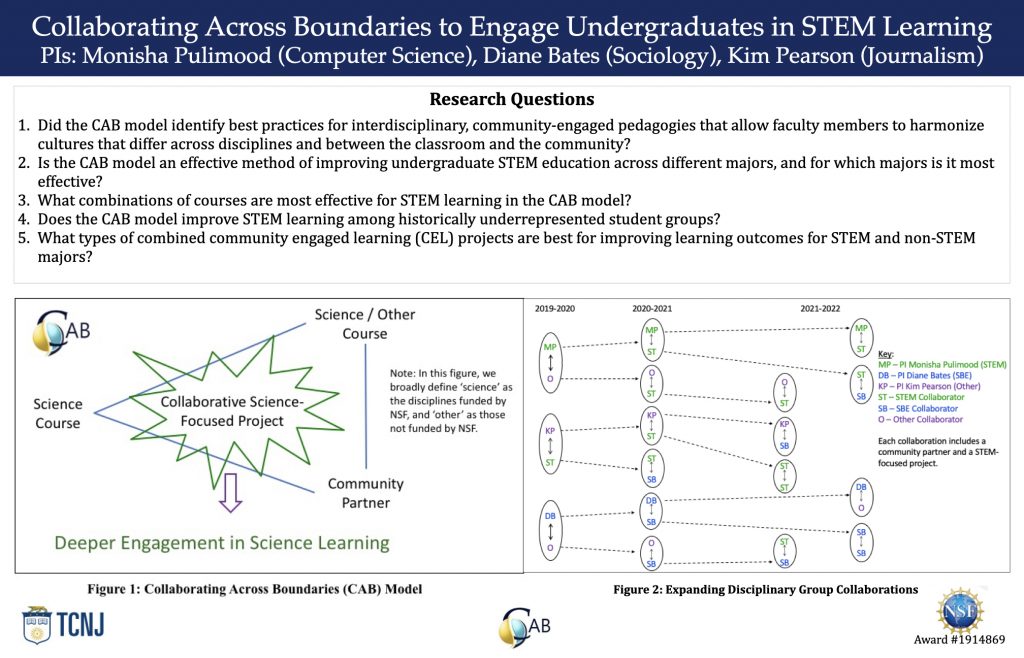

2. Collaborating Across Boundaries Model (CAB)

Phase one: CABECT. The CAB model builds upon these distributed expertise models by adding a community-engaged learning component. Our study, Collaborating Across Boundaries to Engage Undergraduates in Computational Thinking (CABECT), was supported by he National Science Foundation DUE Award #1141170. As Project PI Sarah Monisha Pulimood explains, “The primary goal of the project is to develop a model for students and faculty to collaborate across diverse disciplines and with a community organization to develop technology-based solutions to address complex real-world problems. ” I served as co-PI.

Students in successive classes in computer science, journalism, and interactive media worked with our local chapter of Habitat for Humanity to develop tools that would make it easier for both the agency and potential homeowners to understand what pollutants might be on their properties, along with the the associated cleanup costs.

This project resulted in the creation of the SOAP database (Students Organized Against Pollution), including maps of brownfields, data on contaminants that could be accessed via maps or tables, links to relevant state legislation and other explanatory content. The journalism and media students also developed content on Ushahidi’s Crowdmap platform for eventual incorporation into the SOAP database, and they used Sanborn Fire maps, old industrial directories and Google images to build tables identifying the locations of polluted sites that might have been torn down and repurposed before the establishment of environmental regulatory authorities in the 1970s. They also built an alternate reality game, #TrentonTrending, to allow community members to deliberate over and propose solutions to the challenges presented to the community by years of economic disinvestment and environmental injustice.

Assessment outcomes for the CABECT project were encouraging: students made gains in both computational thinking and civic engagement. More details on the study and the assessment data are available here, here, and here.

CAB: The current work. Our current project, Collaboration Across Boundaries to Engage Undergraduates in STEM Learning, expands the CABECT model across the campus. As we explained in this video for the 2020 STEM for all Video Showcase, by the end of the project, about a dozen faculty, 700 students and perhaps a dozen community partners will have participated in the project by the end of its three-year run. We’ve just concluded our first year.

As you can see from the poster below, the structure of the CAB model readily accommodates collaborations focused on addressing historical and contemporary inequities. Our research questions are focused on STEM learning, but they also include questions related to community engagement and STEM diversity that are best addressed by attention to systemic inequities faced by the community partners, as well as in our classes and curricula. The collaborations we are testing span the range of disciplines and disciplinary combinations, forming a community of practice that is contributing to broader deliberations and actions across campus.

We hope that what we learn will be a useful tool in the broader effort to improve both students’ STEM literacy and constructive civic engagement Our project website will report on our progress.

Not just STEM. CAB PI Monisha Pulimood has extended our model beyond STEM in her capacity as the Barbara Meyers Pelson Chair in Faculty-Student Collaboration. Pelson CAB collaborators also complete an interdisciplinary project. They also participate in the CAB training sessions and workshops, but their outcomes are not assessed as part of the research project.

This past spring, English professor Glenn Steinberg’s Bible as Literature class worked with Music professor John Leonard’s College Chorale class on a performance of Arthur Honegger’s symphonic psalm King David. Steinberg’s students supplied extensive program notes based on their research. Although the Covid-19 shutdown kept the concert from being staged, both the program and a virtual performance of selections from the work will go online later this year.

In the 2020-2021 academic year, Computer Science professor Sherif Ferdous and Communication Studies professor Yifeng Hu will lead teams of advanced research students from their respective departments in a unique collaborative course.

As Hu explained in an email, the course is titled: ‘Virtual Reality for Social, Cultural, and Health Issues’, and multiple student groups will explore different topics surrounding social/cultural/health issues… There will be projects that use VR to raise awareness of racial and/or cultural understanding as well as meeting health communication needs, and to potentially bring about social/cultural/behavioral changes.”

Personal email, July 14, 2020

Conclusion

The challenge of fostering anti-racist pedagogy across the curriculum is both institutional and instructional. At the level of the institution, there must be, as Logan says, respect for the “body of knowledge” generated by scholars on race, racism, and racial inequality. This includes matters that are well beyond the scope of this essay, such as ensuring that support for academic units focused upon these areas is a strategic planning priority as administrators make hard choices during hard times. It also includes fostering faculty deliberation and action on the best ways to ensure that students understand the relevance of these issues across the curriculum.

This essay posits that collaborative classes with interdisciplinary community-engaged projects might be one way to develop both effective instructional strategies and relevant content. The institutional resources required to support such collaborations are already in place in many colleges in universities where offices of community-engaged learning, instructional design and Centers for Teaching and Learning are common. TCNJ’s Center for Teaching and Learning sponsors learning communities that allow faculty to deepen their understanding of issues that affect their pedagogy, often leading to specific actions in the form of campus programming, and administrative initiatives. This could be an ideal place to incubate ideas for teaching collaborations along the lines of the CAB model.

While the protests (or at least the media attention) may subside, the need to address these issues in our classrooms will persist. We have an opportunity to address longstanding inequities and give our students a more comprehensive understanding of their fields of study that will positively inform the kind of professionals and citizens they become.

Acknowledgements

Whenever I talk about this work, I am reminded of the debt of gratitude I owe to many current and former colleagues at TCNJ. I must thank Ursula Wolz, CEO of Riversound Solutions and my former colleague at TCNJ, for inviting me into the world of interdisciplinary computing collaboration. Ursula, Phil Sanders and I collaborated to write the initial proposal for the Interactive Multimedia Major at TCNJ. Ursula was the PI for the first NSF grant for which I was co-PI with Monisha, Broadening Participation in Computing via Community Journalism, which led to the creation of the Interactive Journalism Institute for Middle Schoolers (IJIMS). Reaching back further, I am grateful to TCNJ colleagues Elizabeth Mackie and Terry Byrne. In the early 1990s, we undertook a number of teaching collaborations to give students the experience of creating advertising and merchandising campaigns and launch both print and online magazines.